Lesson 36: Tokoro- the Japanese concept of Place - Grammar Magic

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about the concept of place in everyday Japanese, because this

is something that often confuses people, and I’ve seen even quite good amateur translators getting it wrong.

The word for place in Japanese is, of course, 所/ところ, and we learn this from quite early on.

It means a literal place and it quickly takes on slightly metaphorical uses.

For example, we can say 私のところ, which means “my apartment or house /

the place where I live”.

Come and hang out at my place.

In English, that doesn’t mean hang out as in hang out of the window. It means…

oh, forget it, English is too complicated.

However, in Japanese, the figurative sense of place goes a lot further than it goes in English.

For example, if I say さくらのどこが好きなの?

I’m asking, literally Sakura’s where do you like? or What place of Sakura do you like?

::: info

To quote Dolly-先生 in the comments: ‘どこ means what it always means: what-place?

I was simply demonstrating the use of the place metaphor in more abstract areas. If you look again at the sentence you will see that if どこ meant simply place it would make no sense…’

:::

Now, if I ask this, I’m not expecting an answer like I like her left ear.

An appropriate answer might be something like やさしいだ — “She’s gentle /

What I like about her is that she’s gentle / The place I like about her is that she’s gentle.”

And we might say This is, in my opinion, Sakura’s いいところ’ — “Sakura’s good place

or one of Sakura’s good places”.

So place here doesn’t mean anything remotely like a physical location.

It means an aspect of something, even a really abstract something like a person’s personality.

If I listen to a complicated lecture, someone might say to me 分かりましたか?

— Did you understand it? — and I might reply

分かるところがあったが分からないところもありました —

There were places I understood and places I didn’t understand.

And here, as you see, this is closer to a usage we might have in English:

I mostly understood it, but there were places that I didn’t understand.

This could lead to a subtle misunderstanding in that what I’m most likely to be saying

in Japanese is not that there were times during the lecture when I didn’t understand, but

there were aspects or subtleties that I wasn’t quite grasping.

So, especially if you’re more advanced, it’s good to be aware of this metaphorical depth of the concept of place.

Now, place is also often used to mean a place not in space but in time.

And if we understand this analogy, we can understand certain usages that are often explained

without explaining the structural underpinning for them, which ends up by just giving you

a list of things to memorize and as usual say “well, this goes with this and happens

to mean that and we don’t particularly know why.”

So, for example, we can use ところ — place — with A does B sentences in all three tenses, that’s to say, the past, the present, and the future.

So, for example, if we say, using the plain dictionary form of the word 食べる — eat

(which, as we know, from our lesson on tenses is not present by default; it’s future by default).

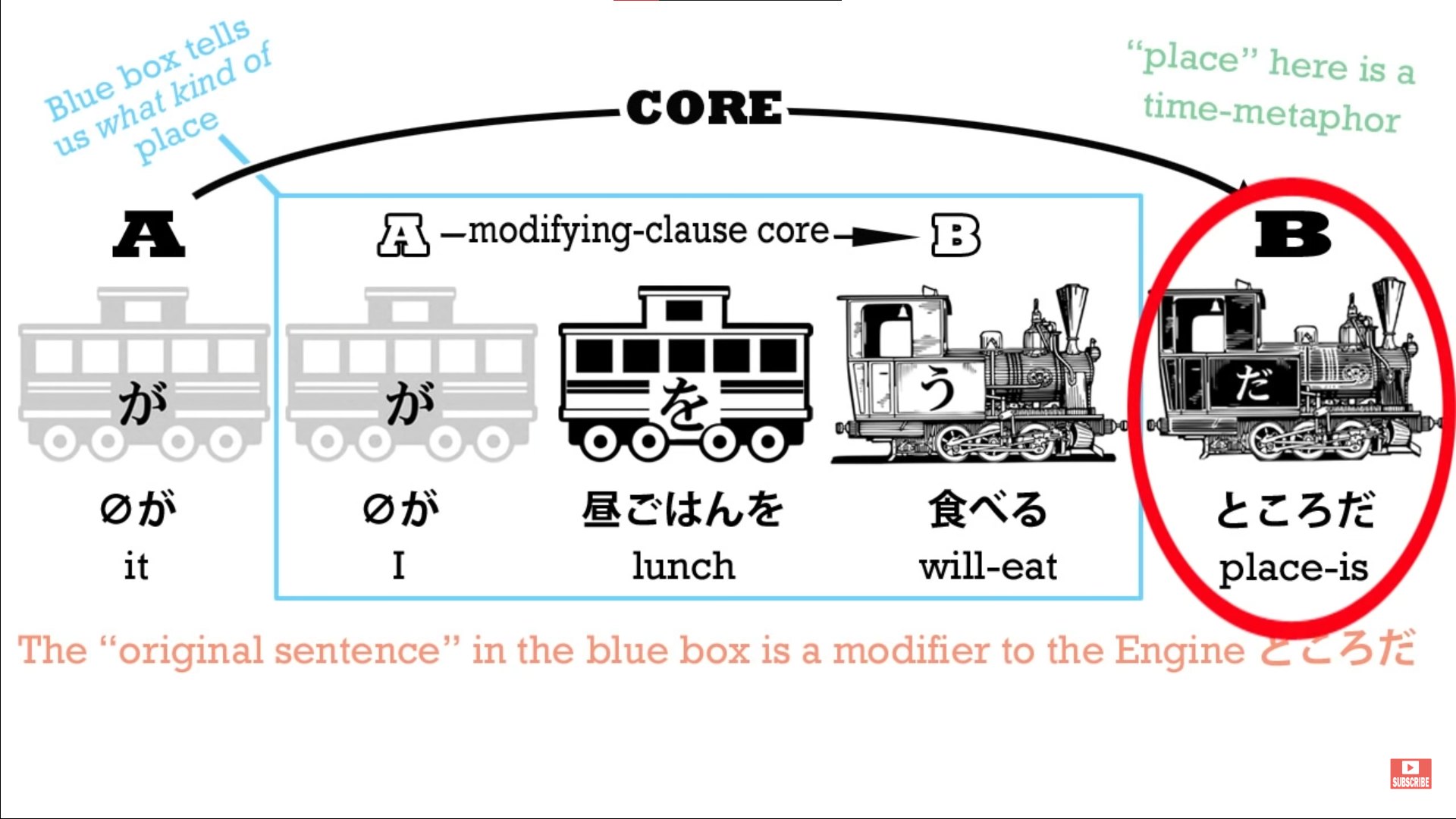

If we say 昼ご飯を食べるところだ, what we’re saying is I’m just about to eat lunch.

What’s the structure of this?

Well, it ends with だ, so we know that what we have is an A is B sentence, even though the original sentence sandwiched into it is an A does B sentence.

So we’re saying that (something) is place.

The zero-car here is it, as it would be in English, and what it means is the present time,

exactly as it does in English when we say It’s time to leave — the present time is time to leave.

The it is the present time in both Japanese and English in these constructions.

So, we’re saying It (the present time) is I-will-eat-lunch time, so what it means is

I’m just about to eat lunch.

So how putting ところだ onto this sentence changes it from what it would mean if we just

said 昼ご飯を食べる is that it’s telling us that we are right now at that place where

I’m going to eat lunch, therefore I’m just about to eat lunch.

NOT I’m going to eat lunch possibly in half-an-hour.

I’m just about to eat lunch right now.

This is the place where I’m just about to eat lunch.

昼ご飯を食べるところだ.

Now, if we use it with the actual present, the continuous present, which is what we use

when we’re actually saying we’re doing something right at this moment, so we say

昼ご飯を食べているところだ, what we’re saying is I’m eating lunch right now.

And just as with the previous example, what that ところだ is doing is making it immediate.

It’s the difference in English between saying I’m eating lunch and I’m eating lunch right now.

Now, in the past, if we say 昼ご飯を食べたところだ, what we’re saying is I just ate lunch.

The ところだ is adding to that past tense the immediateness: “The place in time that

we’re at now is the place where I ate lunch / I just ate lunch.”

Now, in this case we could say 昼ご飯を食べたばかり - I just ate lunch.

The two mean pretty much the same thing.

And I’ve seen textbooks giving us this set of rules : “You can use ばかり with a noun.

You can say このお店はパンばかり売る — This shop sells nothing but bread — or

we can say 昼ご飯を食べたばかりだ — I just ate lunch.

But you have to remember that the rules say that ところ can’t be used with a noun.”

Now, this is true, but it’s a strangely abstract way of putting it.

It’s putting it as if these are just some random rules that somebody made up, perhaps

in the Heian era because they had nothing better to do with their time.

In fact, if we understand the logic of it, we don’t even need to be told this, because it’s obvious.

I can say either I just ate lunch or I can say I’m at the place where I’ve eaten lunch.

We can say This shop just sells bread, but this shop bread place sells doesn’t make

any sense at all, does it? (あのお店はところ売る = wrong)

And this is why I think it’s so important to learn structure.

People sometimes say to me “Am I supposed to be working out all this structure you teach

in every sentence I speak or read?”

And of course the answer to that is No.

What you’re supposed to be doing is getting used to Japanese by reading, listening, and

preferably speaking too. (=The importance of immersion stated right here (๑˃̵ᴗ˂̵))

If you’re not doing that, you’ll never get used to the grammar however many textbooks you study.

But if you understand the structure you won’t be confused by things like whether you can

use ところ with a noun or not, and why can’t you use ところ with a noun when you can use ばかり with a noun, and you have to think all that out.

You don’t have to do that because you understand how it’s actually working.

This is what the textbooks could usefully be teaching, but they don’t.

Now, having learned the structure, it’s also important to be aware of the times when bits

of the structure can get left off.

As with many regular set expressions, the copula だ can be left off, and

more than this, even the end of ところ can be left off.

The ろ can be left off and we can just say とこ.

This is the case in all languages, that there are places where, colloquially, we can leave bits out.

And so long as we know what the structure is, it’s not very difficult to understand the omissions too.

So, we might say 名古屋/なごやに着陸したとこ — I just landed at Nagoya.

And we often use these abbreviations like とこ — leaving off the ろ and the だ

from ところだ — when we are trying to express a sense of immediacy.

But people do it on various occasions, just as they do the equivalent thing in English.

So, we see that ところ can be literal, a place in space.

It can express very abstract concepts like an aspect of someone’s personality, and

it can very often mean a place in time.

And it can be used in various ways as a place in time;

for example, if someone says いいところに来たね?

That is most likely to mean You came at a good time, didn’t you?

NOT You came to a good place, didn’t you?

although in fact it can mean either.

Remember that in Japanese, context is king..