Japanese Punctuation: How it REALLY works. Lesson 90

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about Japanese punctuation.

Now, the first thing we need to know about about Japanese punctuation

is that most of it is a relatively late arrival in Japanese.

Most of it came in during the Meiji era, about a hundred and fifty years ago.

This was when Japan was modernizing, and a lot of the reason it came in

was to help in translating Western literature.

Now, what this means is that in most cases Japanese punctuation doesn’t have

such fixed and structural meanings as the equivalent punctuation does in English

and other European languages.

So, we need to know what the punctuation is doing and also what it isn’t doing.

The full stop / 。

So, the first mark we’re going to look at is the Japanese full stop or まる / 。,

which looks like a little circle at the foot of a letter.

And this is really the exception to the rule, because it really is structurally clear.

What it does is end a sentence.

And this is very important for us in understanding how complex Japanese sentences are structured.

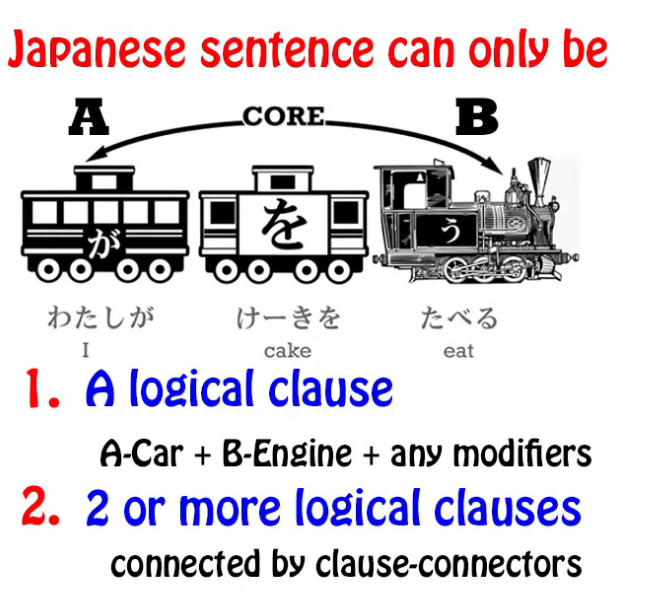

Why is that? Well, Japanese is a very modification-heavy language.

That’s to say, a lot of what other languages do by other strategies, Japanese does by modification, that’s to say, using clauses to modify nouns or other elements of a sentence.

Most of the heavy lifting in Japanese structure that’s not done by logical particles

is done by this modification structure.

So whole logical clauses can be used not as logical clauses

but in order to modify a noun or some other element.

So, let’s take a look at how this works.

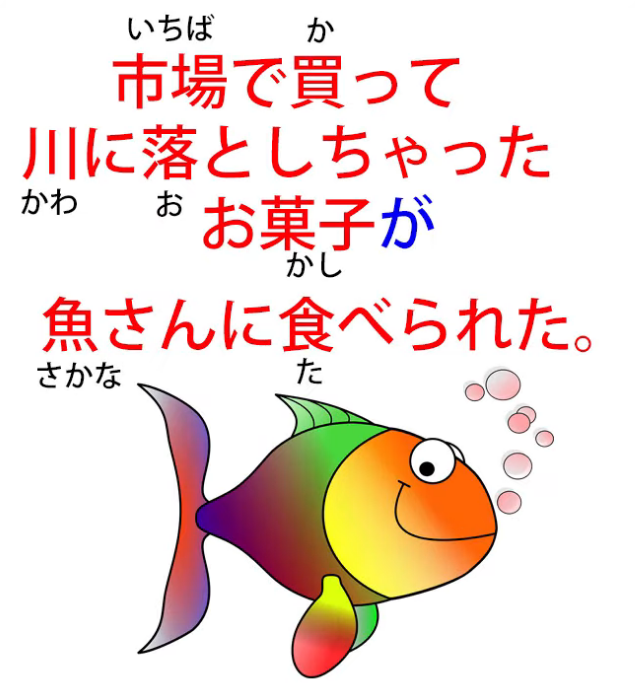

市場で買って川に落としちゃったお菓子。

And this means The candy that I bought at the market and done dropped in the river.

::: info

I guess, done in the translation is used to point out the more literal translation of ちゃった.

:::

Now, the problem with this when we’re reading a complex sentence is that we can get confused

about whether something is a logical clause or not.

So, are we saying here that I bought something at the market? No, we’re not saying that.

Are we saying that I dropped something in the river?

No, that’s not what we’re saying in this sentence.

Both of those things are just modifying お菓子.

They’re telling us what kind of an お菓子 it was:

the one I bought at the market and done dropped in the river.

So all we have here is a single noun, お菓子, that’s been heavily modified by logical clauses

that aren’t working as complete logical clauses.

We can then add a logical particle to that お菓子 and make it into a whole logical clause.

So, we might say, 市場で買って川に落としちゃったお菓子が魚さんに食べられた。

The candy*(=subject)* (I) bought at the market and done dropped in the river got eaten by a fish.

::: info

If I understand correctly, because we marked お菓子 with が subject, we can now build another clause out of it, hence we get another logical clause of お菓子が魚さんに食べられた.

:::

While お菓子 is also modified by modifier clauses before it, specifically 市場で買って川に落としちゃった, they serve here as simply a modifier that describes お菓子 rather than being complete (standalone?) logical clauses. Although just my guess from how I understand it.

But how do we ensure when we’re reading a sentence like this whether we’re looking at

a logical clause or whether we’re looking at a modifier?

How to know if it is a logical clause or a modifier?

Now, the important thing to understand here is that in any kind of Japanese writing

(except perhaps on Twitter or something)

a logical clause has to end in one of two ways,

either with a まる / 。, which tells us that it’s the end of the complete sentence —

(it may have a couple of sentence ender particles after it, but it’s a very strict rule of Japanese

that what ends any logical clause is the B-engine, aside from any sentence-ender particles) —

or it has to end in a clause connector that completes the clause and leads into the next clause.

This may be the て-form, it may be a word like から or けれど,

but armed with that information we can then see what’s going on.

So, let’s look at 市場で買って川に落としちゃった.

That’s a complete pair of logical clauses.

::: info

My guess here is that it is theoretically composed of two logical clauses if, like Dolly says below, we presume there is some hidden subject and a hidden direct object if we took both verbs as marking their individual logical clauses - 市場で(私がお菓子を)買った and (私がお菓子を)川に落としちゃった that are then connected using the て-form. Here, お菓子 should be a direct object hence why を, since 落とす and 買う are other-move verbs & require a Subject acting on a Direct Object. Obviously, topic marker can be there too, as 私は in the beginning.

:::

But instead, these clauses are combined and since they are followed by a noun serve instead as a modifier for that noun, so therefore they are not logical clauses anymore and do not contain the hidden elements, where instead they are one single big modifier for a noun that is following them, in this case お菓子. It is a shame I cannot ask Dolly about this, as I feel it would help a ton

However, I am aware my guess might very likely be wrong, so please take it with a lot of salt.

It’s not telling us what it was that we bought in the market and dropped in the river,

but it could perhaps be presuming that.

But we know that it’s not in fact a logical clause

because it doesn’t end in a clause connector and it doesn’t end with a まる / 。.

It goes straight into a noun.

And this is how we can tell the difference between a modifier and a logical clause.

And we know when the entire sequence, the entire sentence,

is over because it’s going to have that まる / 。.

And I’ve done a video about this method of analyzing Japanese sentences

and I’ll link that so that you can follow it up afterwards (Lesson 34).

But the まる / 。 here is vital.

The comma / 、

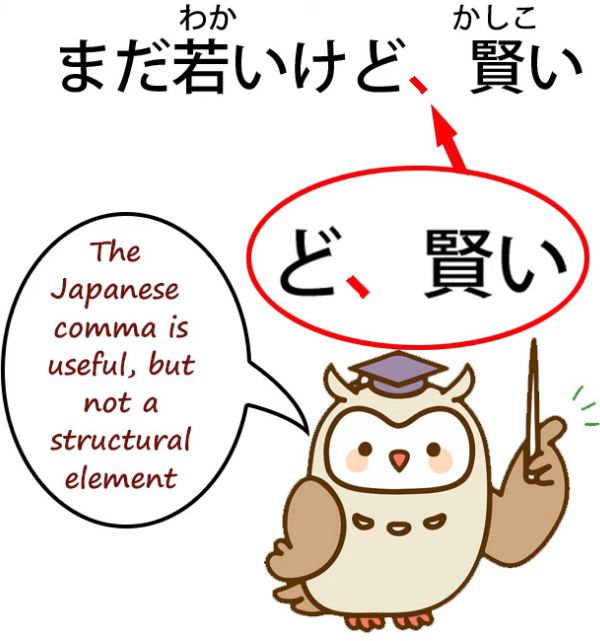

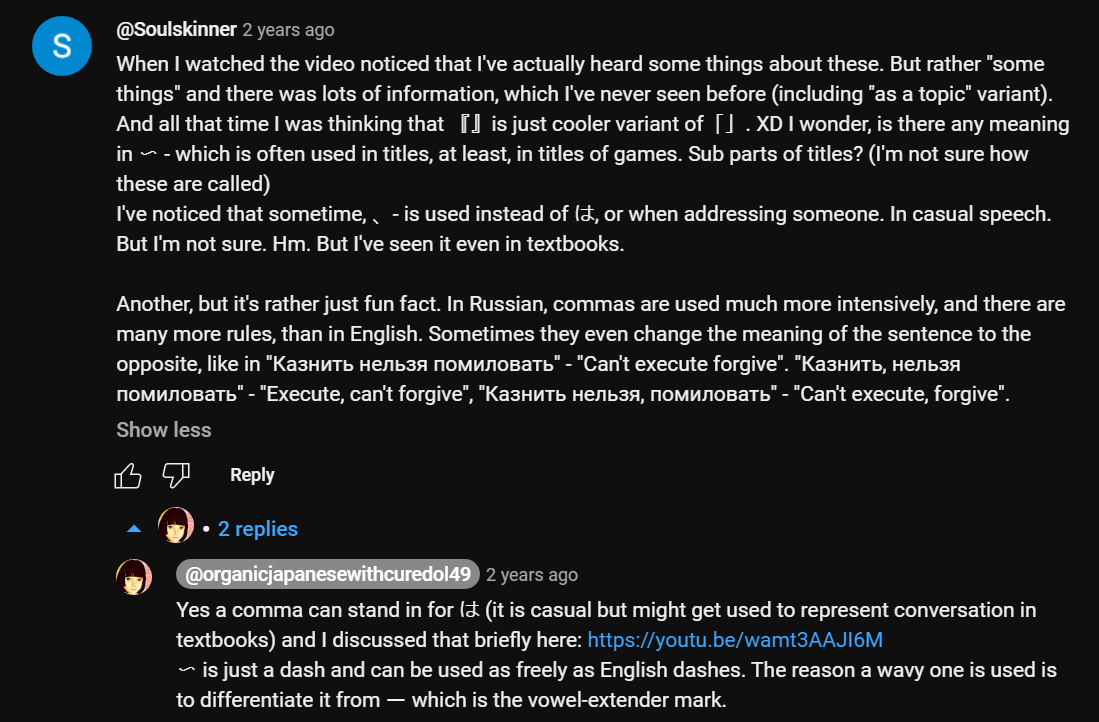

Now, the next one we’re going to look at is the Japanese comma,

which looks like a little diagonal line at the foot of a letter.

And that’s kind of the opposite of a まる / 。,

because it really is not a logical element in the sentence.

It was adopted into Japanese, but unlike the English comma or other European commas,

it has no logical rules.

Ideas like sectioning off a subordinate clause with commas at each end, that doesn’t exist in Japanese.

You just put in a comma wherever you want to indicate a pause. And that’s all it does.

In Japanese schools, students are discouraged from using too many commas,

and the reason for this is not incorrect comma usage,

because there is no such thing as incorrect comma usage in Japanese.

The reason is that commas are not a structural part of Japanese, so students are discouraged

from using them as a crutch in conveying their meaning.

If you can’t convey your meaning without commas, then you’re not writing good Japanese.

The question mark / ?(はてな)

Now, the next one we’ll look at is the question mark or はてな.

Now, in English the question mark is subject to a rule.

If you have a question, you have to end it with a question mark.

And also in English, questions are structurally different from statements.

So if we say, The coffee is hot, that’s a statement,

but if we say, Is the coffee hot? that’s a question.

In Japanese we don’t have this differentiation.

Statements and questions are structured exactly the same.

Now, in formal Japanese we have the question-marking particle か,

which tells us that it’s a question.

But in informal Japanese we can use か but mostly we don’t.

Sometimes we use the question-marker の, but that’s ambiguous because

の can also be a statement marker.

The only way you can really tell a question from a statement in Japanese

is the rising intonation, which of course you can’t hear in text.

And so the question mark has become a very useful tool for indicating that rising intonation,

for telling us that this is a question, not a statement.

In English, you have to use the question mark at the end of a question

if you’re writing proper English. In Japanese, there’s no such rule.

If the か marker is there, you don’t use the question mark,

but if you want to disambiguate the fact that something is a question

rather than a statement, you just pop in a question mark if you want to.

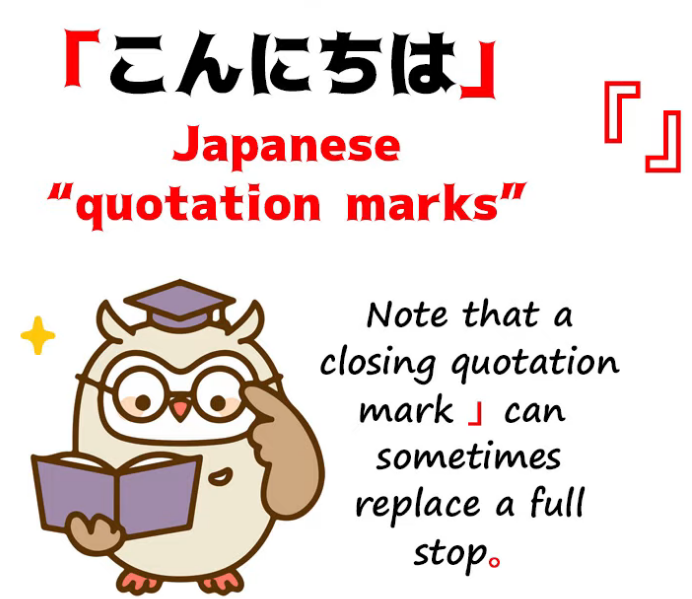

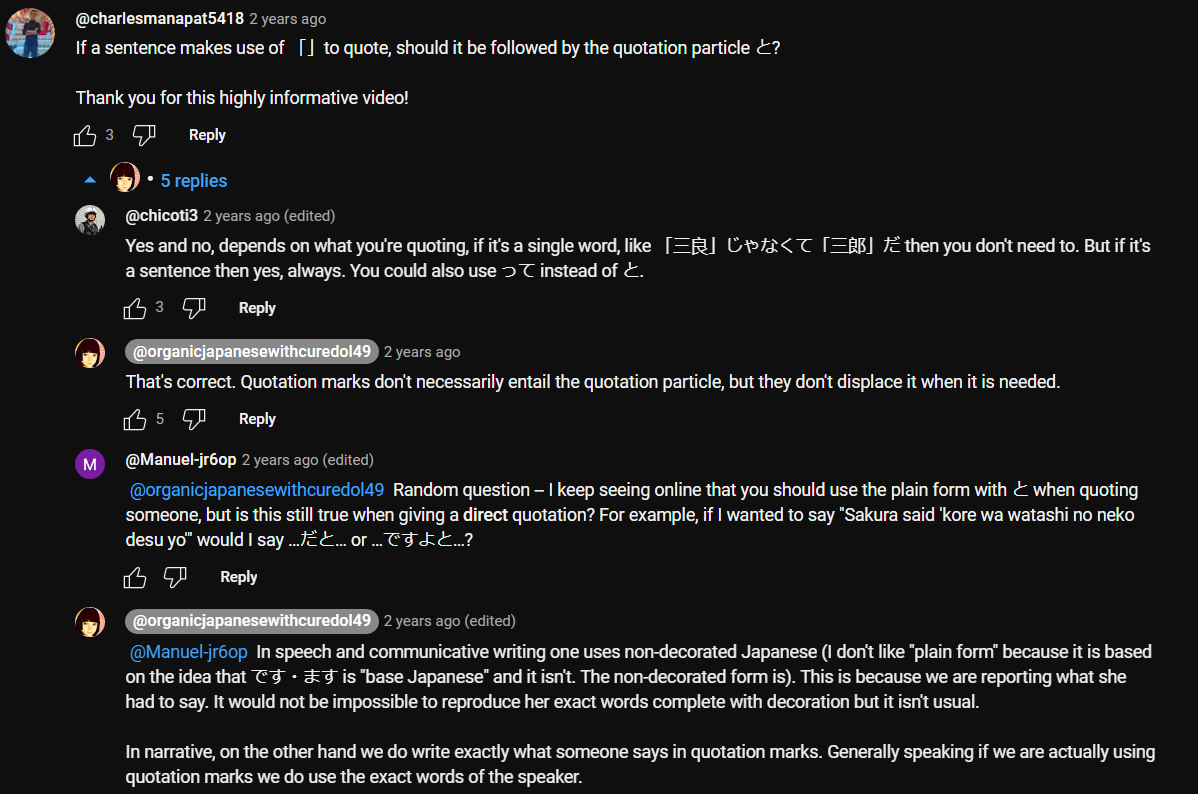

The quotation marks / 「 」

The next thing we’ll look at is quotation marks.

These look like little square brackets at the ends of a statement,

and they work exactly the same as English quotation marks.

They just tell us that something is a quotation: it’s what somebody’s saying.

We don’t use them for what somebody’s thinking, as we sometimes do in English.

Now, sometimes you’ll see double quotation marks like this, 『 』

and what they do is mark a quotation that occurs inside another quotation.

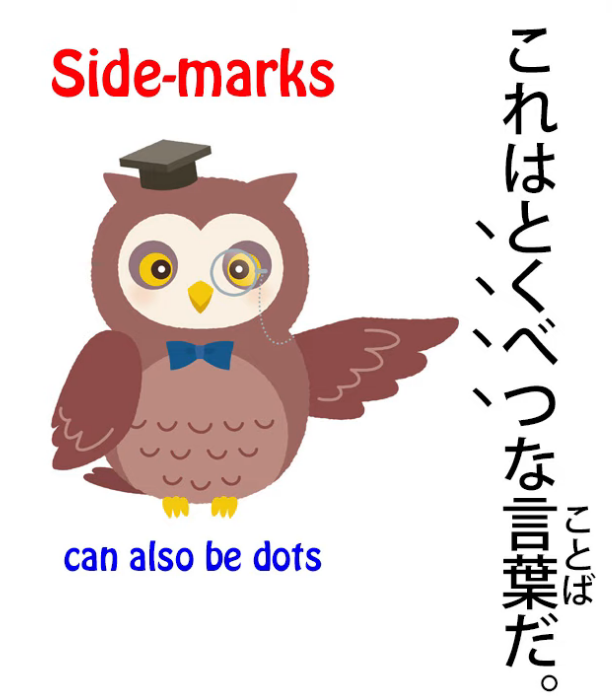

The side-marks

Now, the last thing I want to talk about is something that really puzzles people quite a lot.

In Japanese, particularly Japanese books, you’ll sometimes see,

especially in vertical text, a set of little marks that look a bit like Japanese commas,

running along the left-hand side of a word or a phrase.

What on earth is this doing?

Nobody seems to tell you.

What it is actually doing is either emphasizing that word or phrase

or telling us that it’s being used in a special sense.

So what these little marks are really doing is something like

putting something into italics in English.

And I suspect they came into Japanese

in the first place to render italicization when translating Western literature.

There’s no way of really writing Japanese characters in italics.

There is no italic format for Japanese, so this is what’s used instead.

This emphasis and the indication that something’s being used in a special sense

can also be indicated by katakana, but you will see this from time to time

in Japanese texts and that’s what it means.

Dolly’s link is for Lesson 80.