なんて Nante なんか Nanka など Nado: 3 Common words clarified. Lesson 82

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about three words that you’ll encounter often in your immersion.

They have quite a wide meaning spectrum, and that means that

dictionaries can’t really cover the full range of what they mean,

especially when, as they often are, they’re used in very colloquial ways.

And I’d like to thank all the people who tell me which words give them trouble in immersion.

This helps me to know what to cover and in what order to cover it.

A lot of people wanted to know about なんて and なんか.

So if you have words that are giving you trouble, please pop them in the Comments below.

It’s very helpful to know what it is that’s causing problems.

So, the three words are など, なんて and なんか.

They have different meanings but they overlap in certain areas.

And the simplest one is など, so we’re going to start off with that.

など

など essentially means pretty much what etcetera means in English,

but the thing to bear in mind in formal language is that

it has higher status than etcetera in English.

In English, etcetera tends to be treated in many cases as a bit of a cop-out.

It’s a way of not really saying exactly what you mean.

In Japanese it has much higher status. Its meaning spectrum is broader.

You will encounter it both in completely formal writing and in informal conversation and writing.

It’s an indispensable part of the language.

To give an example of its formal use, a dictionary definition of the word 車窓 —

and 車窓 is one of these words that I’ve talked about in a previous video,

two-or-more-kanji words that really aren’t words in quite the English sense of the word,

that’s to say, they are really phrases.

They bring together two known entities, which are known if we’ve done much Japanese,

into what in English would simply be a phrase.

So we can throw these words into our Anki if we want to remind ourselves that they exist

but we shouldn’t treat them as completely new entities.

They’re really just like phrases and this one is very close to the English phrase

car window, which isn’t a word, it’s just a phrase.

If we know car and we know window, we know what a car window is.

So if we know 車 and we know 窓 and we know the on-readings of the two,

which are しゃ and そう, then しゃそう really presents no problems,

except that we need to remember that しゃ, the on-reading of 車/くるま,

refers to a broader range of vehicle.

くるま usually simply means a 自動車/じどうしゃ (an automobile)

while しゃ can refer to any kind of surface vehicle.

A bicycle is a 自転車/じてんしゃ, a train is a 電車/でんしゃ, etcetera.

And the definition is: 自動車などの窓.

So essentially that means the window of an automobile, etcetera,

which in this case means any kind of a surface vehicle that has windows,

so not a 自転車 but a 電車, etcetera: the window of a vehicle.

::: info

Notice how the など here is used right after 自転車 (preceding even the の particle).

など seems to be used directly after its noun / noun phrase like any other particle would (など is a particle too). Furthermore however, looking at some Yomichan sentences where it is used, it seems like it takes priority over the logical particles like の, が, を in that it is the first one to attach to/after its attached noun, with the logical particles following it only once it was attached. As seen above or in a sentence from Yomichan:

大学では

フランス語やドイツ語などを勉強した。

:::

And this など is a very typical use of the word.

It gets used freely in formal and informal Japanese.

など in informal Japanese

In informal Japanese, など also has another use,

which overlaps with the other two words we’re going to look at.

It can be used to mildly denigrate or belittle a word that it’s attached to.

Now, denigrate and belittle are not exactly the right words to use here,

but I don’t think there are quite the right words in English.

It throws a negative light, which in the case of など is usually making light of

or slightly rejecting whatever it is.

So we might say, タバコなど不要だ, which means I’ve no use for cigarettes.

Now, タバコは不要だ would mean the same thing essentially

(notice that など knocks out other particles). - so Dolly confirms my observation from above, except that here it straight-up removes the は particle, likely because it is not a logical particle.

The only difference here is that など is throwing

that slightly disparaging light on cigarettes.

So the way we could read it is something like, in English, I don’t need stuff like cigarettes.

Now, actually this doesn’t mean that literally.

It’s not saying I don’t need cigarettes or cigars or a pipe or a hookah.

It means I don’t need that kind of thing — that’s something I don’t need in my life.

And as I say, this use overlaps with our other two words.

Both なんか and なんて can be used in this

throwing-a-negative-light-on-the-noun-they-follow way.

The strongest and most colloquial of the three is なんか,

and なんて comes somewhere in the middle.

なんか

So, なんか is really a contraction of 何か/なにか (something),

but it has quite a few colloquial uses.

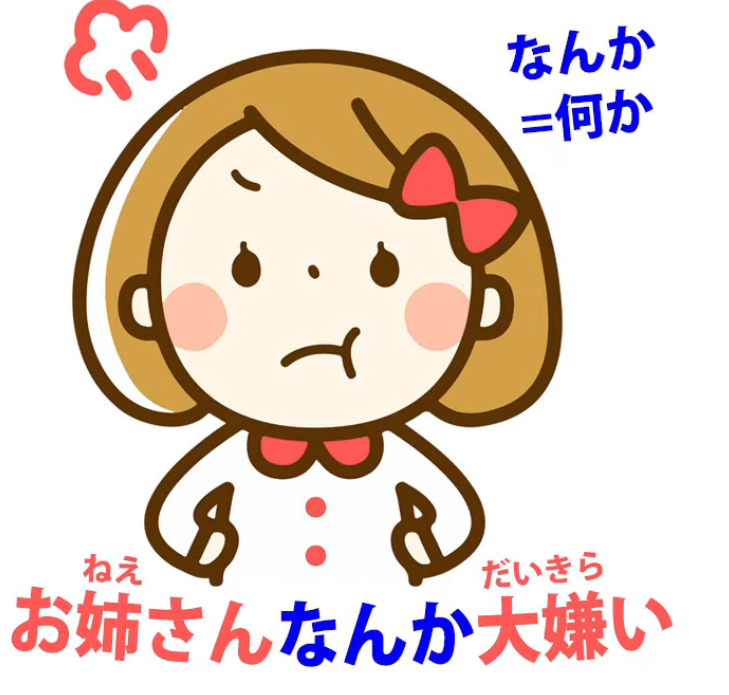

And it’s the denigrating one we’ll hear sometimes very strongly in cases where…

well, let’s say in an anime a younger sister is angry with her older sister.

She may say, お姉ちゃんなんか大嫌い! (I really hate stuff like my big sister).

Now, of course, that’s not literally what she means.

She doesn’t mean she hates stuff like her big sister,

but by using this expression —stuff like you, stuff like my big sister —

you’re throwing a very disparaging light on what it is you’re talking about.

It can be milder: we can say, サッカーなんか興味がない

(I’ve no interest in stuff like soccer / I’m not interested in soccer).

And it can be more mildly belittling still: we might say, 雨なんか平気だ.

And what we’re saying there is “(Stuff/Something like) Rain doesn’t bother me /

I’m not troubled by (stuff/something like) rain / I’m okay with (stuff/something like) rain”.

And the なんか is just throwing that slightly diminishing light on the rain,

indicating how little we’re worried about it.

なんか used with oneself

And it often gets used of oneself, as in 私なんか,

and this is often used to stress a perceived inferior position

or a difficult position that one finds oneself in, for example,

私なんかまるで子供扱いだ (I’m treated just like a child).

なんか - contraction of なにか / 何か

Now, the fundamental meaning of なんか, as I said, is actually

a contraction of なにか / 何か, which is something.

And it can be used simply as a contraction of なにか / 何か in, for example,

なんか心配はある?, which just means 何か心配はある or

(Is there some worry? Is anything worrying you?).

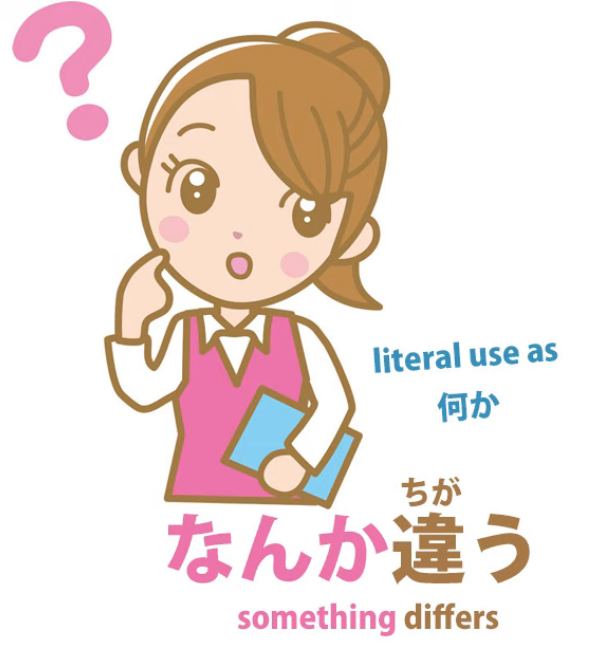

なんか as something, somewhat to make things vaguer

Now, from there it goes on to preface things in order, as with something

or somewhat in English, to make them a bit vaguer.

So we might say なんか違う (something’s different / something differs —

I’m not sure what it is, but something’s different).

なんか違う.

なんか as somehow / for some reason

Now, from that it goes on to meaning somehow.

So we might say なんか好きじゃない (somehow, I don’t like it /

For some reason, I don’t like it).

なんか好きじゃない

なんか in very casual / sloppy speech as kinda x

Now, from there it gets worse.

It goes on to become even vaguer.

So in very casual and (I would say) rather sloppy speech,

you can hear なんか at the beginning of a sentence

and then several times during the sentence: なんか this, なんか that.

And when it’s being used like that, it’s really being used like kinda or like in English.

And, just as in English, this is a sloppy way of talking.

It’s not good Japanese, but you may hear people talking like this in some anime, etcetera.

The function really, as with like or kinda in English, is

simply vaguing things up a bit and

releasing oneself from the need to express oneself precisely.

Just kinda saying, like, whatever it is that kinda comes into your mind, like —

なんか… なんか… なんか.

So, we should look out for this very loose use of なんか

and realize that it doesn’t really mean very much at all.

なんて

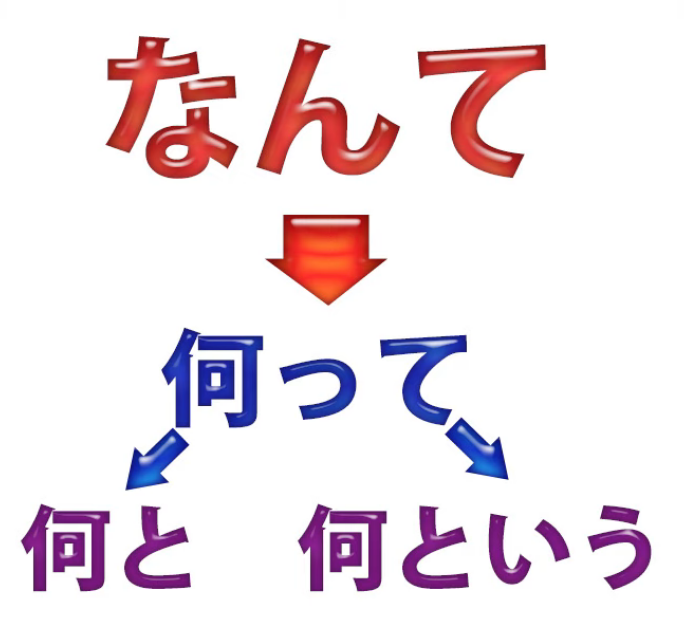

なんて is essentially a contraction of 何って

and I’ve done another video about this -って, which is a contraction of -と or -という.

(Lesson 18)

And it’s the same with なんて.

So, in its simplest and most basic use, it’s used, for example,

in saying なんて言った?, which means what did you say?

English speakers may be tempted to ask

なにをいった? (what did you say?).

But that’s not natural Japanese.

We can say なんと言った, but it’s actually more natural in casual speech

to say なんて言った? (what was it that you said?)

which isn’t very easy to translate into English because

it’s using that quotation particle (the と) even though

it’s rather morphed itself into なんて in colloquial speech.

なんて as What a (this) or What a (that)

Now, you’ll also see it a lot with a meaning of what in English

as used in expressions like What a nice day!,

What a stupid person!, What a beautiful flower! etcetera.

And this is an abbreviation of なんという / 何という, but it’s more often than not,

even in not particularly casual speech, used as なんて.

なんて美しい景色だ! (What beautiful scenery!)

And, just as in English, this なんて can be used to introduce

any fairly strong reaction to anything.

It can be negative; it can be positive.

We’re saying what a (this) or what a (that).

なんて used in a belittling manner

Now, it’s also used, as we said before, in this belittling manner attached to a noun.

So, for example, we can say 試験なんて嫌いだ (I hate exams);

お金なんていらない (I don’t want money).

Like なんか, it both stresses the noun that it follows

and indicates a negative or a dismissive attitude towards it.

なんて used to express surprise

And it can also be used at the end of a complete statement to express surprise.

So in this sense it’s rather like the first one we looked at,

the what a (this) or what a (that), which comes at the beginning.

It can also be used at the end to express surprise or in some cases disbelief or doubt.

So we might say, 冬に燕を見るなんて

(see a swallow in winter + なんて).

What’s that なんて doing?

Well, it’s turning the whole thing into an expression,

rather like the what a (this) or what a (that) expressions.

So what we’re saying is something like Gosh, imagine seeing a swallow in winter!

And this use of なんて on the end, after the engine of a statement,

can be used as part of a longer sentence.

So, for example, we could say 腹を立てるなんて君らしくない.

Now, 腹を立てる means literally stand your stomach,

but this is an expression meaning get angry.

So the whole thing is saying getting angry, that’s not like you.

And I’ve talked about this らしい and らしくない in another video. (Lesson 25)

So, if you’re not familiar with those, I’ll put a link above my head

and in the information section below.

Now, we can take out the なんて here and then of course we’d have to put in a particle

and say, 腹を立てるのは君らしくない.

But the なんて is expressing our surprise about this

because it’s not like the person concerned.

And note that this can’t be the belittling なんて, which attaches to nouns.

This is attaching to a complete statement,

so we’re expressing our surprise about someone being angry

and then adding the comment that it’s not like her.

なんて as this vague という

And finally, we can use it in a way that comes right back more or less

to the original meaning of -という, but adding a bit of vagueness to it.

So if we say 山田なんて人は知らない,

we’re saying I don’t know anyone called Yamada.

Now, the なんて here could be replaced simply with -という:

山田という人は知らない.

So what’s the difference between using the regular -という and using なんて?

Well, 山田という人は知らない is like saying in English simply

I don’t know a person called Yamada.

But 山田なんて人は知らない is more like saying

I don’t know any character called Yamada.

It’s throwing a lot more doubt and questioning into the whole thing.

So, we’ve covered the main usages of these three words or expressions here.

It’s not completely exhaustive, but I think it gives you the basic keys

to how they work, what they mean, how they’re used.

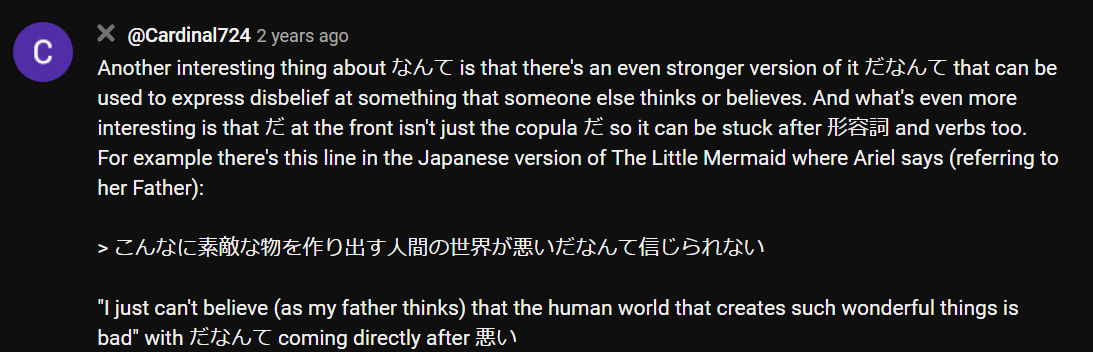

::: info

Damn, quite a few sub-titles in this one, heh* (ノ*°▽°*)

Wanted to make it a bit easier to search, if anything. Also, this is quite interesting:

* *

*

Sorry for the microscopic font, Youtube again hides the text parts if I zoom-in for some reason…

:::