Lesson 22: Te-wa, te-mo - topic/comment magic! How 〜ては and 〜ても REALLY work

こんにちは。

Today, we’re going to go back and cover that little bit of Alice that we skipped last week

and that’s going to give us the opportunity to look at

the て-form + は and the て-form + も and some other things too.

So we’re going to return to the point where Alice had just taken the marmalade jar off the shelf.

でも, びんは空っぽだった – But the jar was empty.

空/から means empty, and you can see it has the kanji for sky (空 as sky is read そら),

which I guess is the biggest empty space in this world.

空 – empty – is the から in 空手, which is the art of fighting with empty hand, without any weapon.

空っぽ is a kind of strengthening of empty, meaning there was nothing in it, it was completely empty.

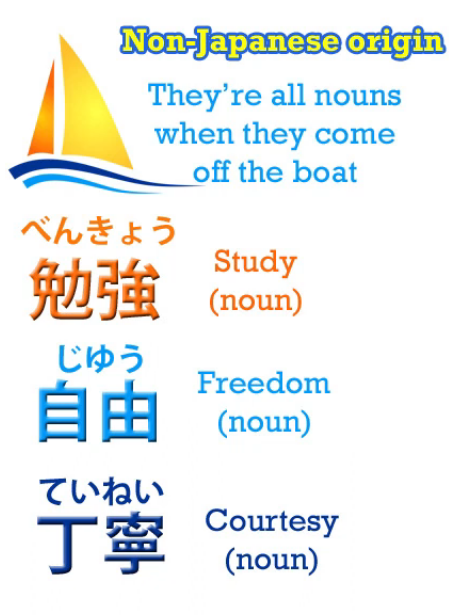

And 空っぽ works as a noun, and generally speaking if you don’t know what kind of word a word is in Japanese, it’s most likely to be a noun.

Japanese is quite a noun-centered language, because all the words that come in from other

languages like Chinese, of which there are a huge amount, and English, and other languages too come in as nouns.

You can turn them into verbs by putting する after them;

you can turn them into adjectives with の and -な.

But fundamentally they’re nouns.

So it’s always a good guess when you don’t know what a word is,

that it’s quite likely to be a noun.

空っぽ is a noun, empty.

でも, びんは空っぽだった – However, the jar was empty.

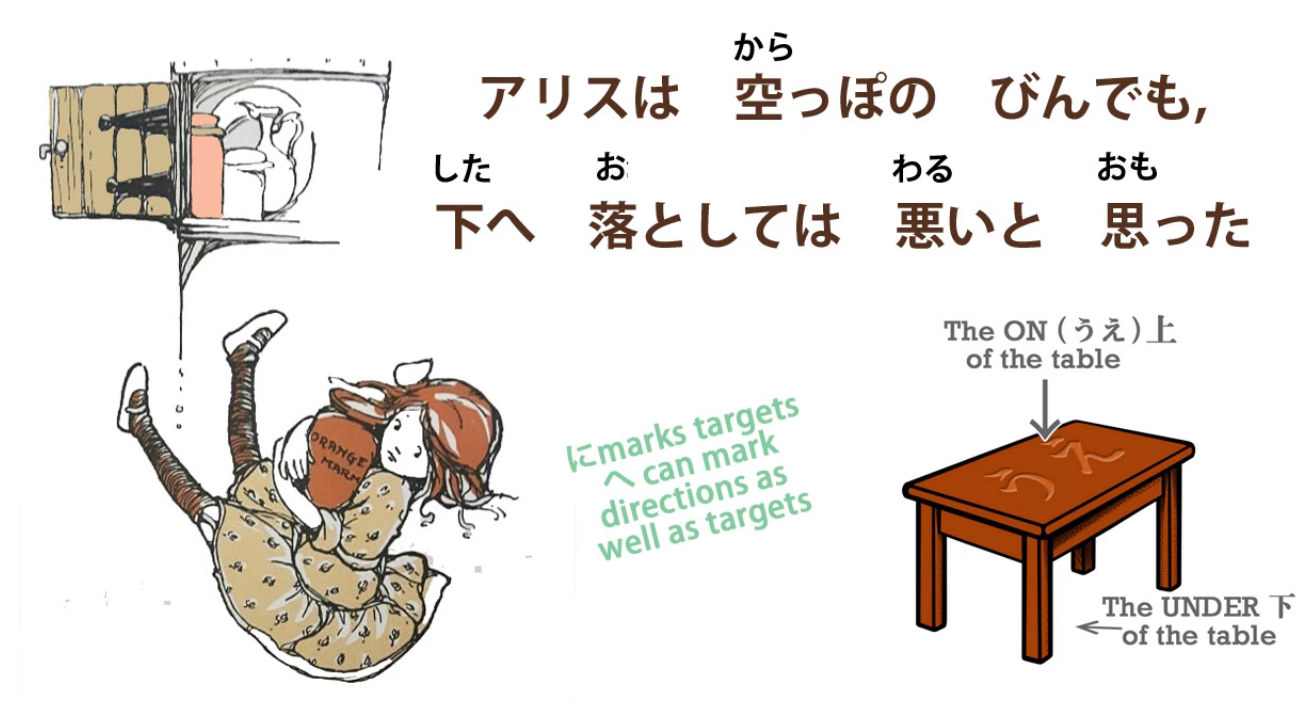

アリスは空っぽのびんでも下へ落としては悪いと思った.

Here again, we’re going to see some other uses of the て-form.

でも / ても

First of all,

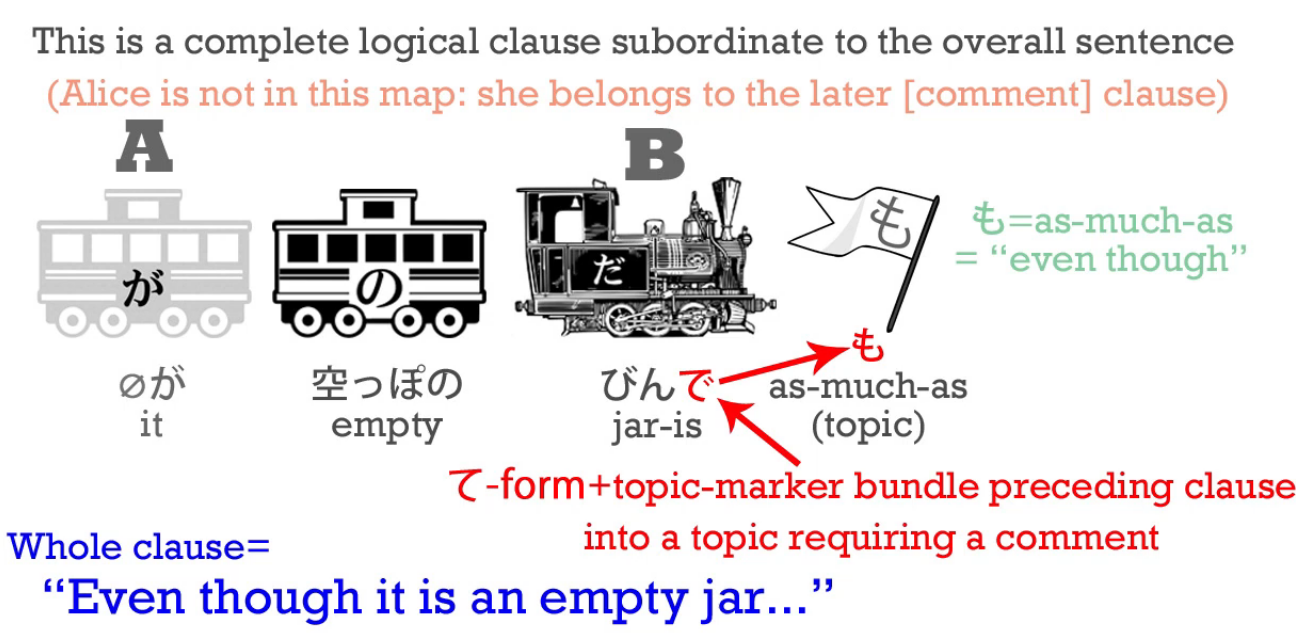

アリスは空っぽのびんでも.

Now で here is the て-form of だ ,

and も, as we know, is the additive, inclusive sister of は: the additive,

inclusive non-logical topic-marking particle.

So, 空っぽのびんでも.

で, て-form of です, is it was (an empty jar) –

and でも means even though it was (an empty jar).

も can be used to mean as much as –一万円もかかった – it took as much as 10,000 yen / cost as much as 10,000 yen) –

でも means something like as much as it was (an empty jar) / even though it was (an empty jar).

And I’ve done a video on these uses of も that you may want to watch.

And we also use this -ても form when asking for permission, don’t we?

ケーキを食べてもいい?

– Is it all right if I eat the cake? / May I eat the cake?

Literally, If I go as far as to eat the cake, will that be all right?

空っぽのびんでも下へ落としては悪いと思った.

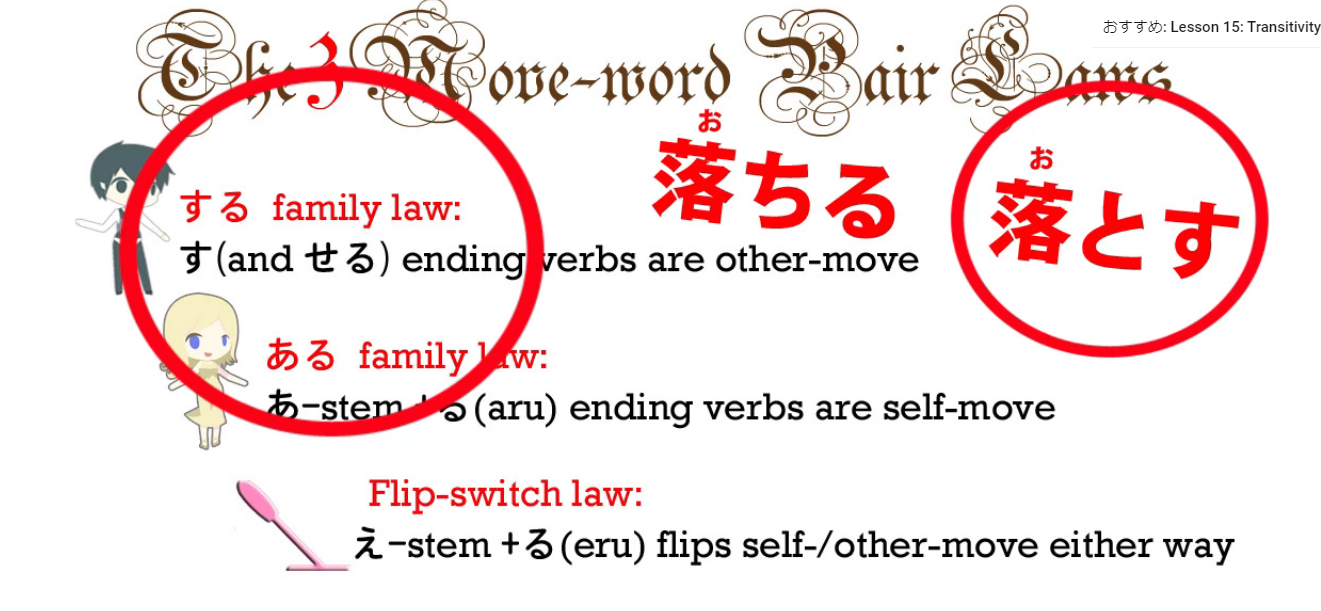

落とす means to drop. It’s another one of our self-move/other-move pairs.

落ちる means to fall – that’s self-move: a thing falls, by itself.

落とす, which ends in -す, according to the first law of self-move/other-move verbs, so

it means drop: we don’t drop ourselves, we drop something else.

下へ : now, -へ, as we know, is the other targeting particle.

It’s very similar to に, but the difference is that -へ tends to refer more to the direction

something is moving than to its actual target.

So in this particular case, 下に落とす wouldn’t be right.

We’re not saying that we’re dropping it to a particular target, like テーブルの下

– the under of the table / under the table.

We’re just dropping it downwards, dropping it in a downward direction.

We don’t even know what’s down there.

She did try looking and she couldn’t see much.

So dropping it in the direction of down – 下へ落とす.

Now, したへ落としては悪い.

Now here you see, we’ve just had て-form plus も; now we have て-form plus は.

And we know that も and は are the opposite twins.

While も is the additive, including particle, は is the subtractive, excluding particle.

So, while -ても means as much as, -ては means as little as.

ては

Now, we tend to use -ても in positive contexts – If I do as much as this, will it be all right?

But we use -ては in negative, forbidding contexts – don’t even do as little as that.

So we often say, -てはだめ – do that is no good / do that is bad / if done (action), no good.

In this case, it’s very similar: 落としては悪い – even as little as dropping it would be bad.

The point isn’t really that dropping it is a small thing, or that eating the cake is a big thing.

The point is that we can go as far as eating the cake, that’s fine, but don’t even think

about dropping it: 落としては悪い – doing that is right out of the question.

Very often this forbidding -ては is just contracted to -ちゃ.

笑っちゃだめ!- Don’t laugh! / Even as little as a laugh is no good. (roughly)

Now this pattern continues into other uses of -ては.

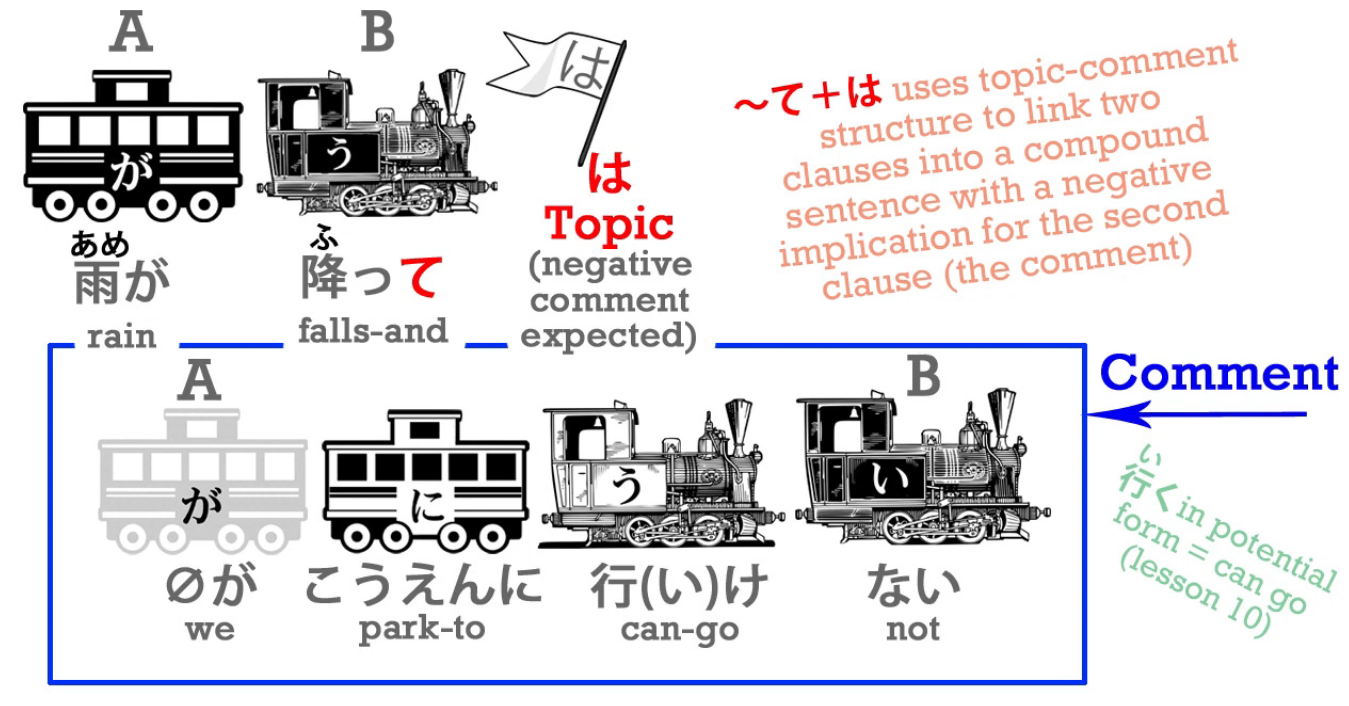

ては as a connector between two clauses

For example, we can use -ては as a connector between two clauses and

it implies that the second clause is unwanted or negative.

So we can say, 雨が降っては公園に行けない – It’s raining and we can’t go to the park.

Now, as we know, -て can connect two sentences and if we just said,

雨が降って公園に行けない we’re saying – It’s raining and we can’t go to the park.

There’s an implication that we can’t go to the park because it’s raining but there’s

no suggestion of whether we’re happy or unhappy with the result.

雨が降っては公園にいけない is indicating that the result is unpleasant or unwanted.

And you can see that this does have its root in the restrictive quality of は.

For example, in English we might say, Just because it’s raining, we can’t go to the park

and this is exactly what は means, doesn’t it?

::: info

Bread is the direct object here (like in English).

:::

If we say パンを食べた, we’re saying I ate bread, but if we say,

パンは食べた that often implies I ate bread but I didn’t eat something else.

::: info

Speaking of the bread, (I) ate. (rough translation), bread is the topic of the convo I guess?

:::

Conversely, if we say, パンを食べなかった, we’re saying I didn’t eat bread; if we say

パンは食べなかった, we’re often implying I didn’t eat bread, but I did eat something else.

雨が降っては公園に行けない originally could imply something like

Just because it’s raining, we can’t go to the park,

but now (with ては) its implication is more

Unfortunately, because it’s raining, we can’t go to the park.

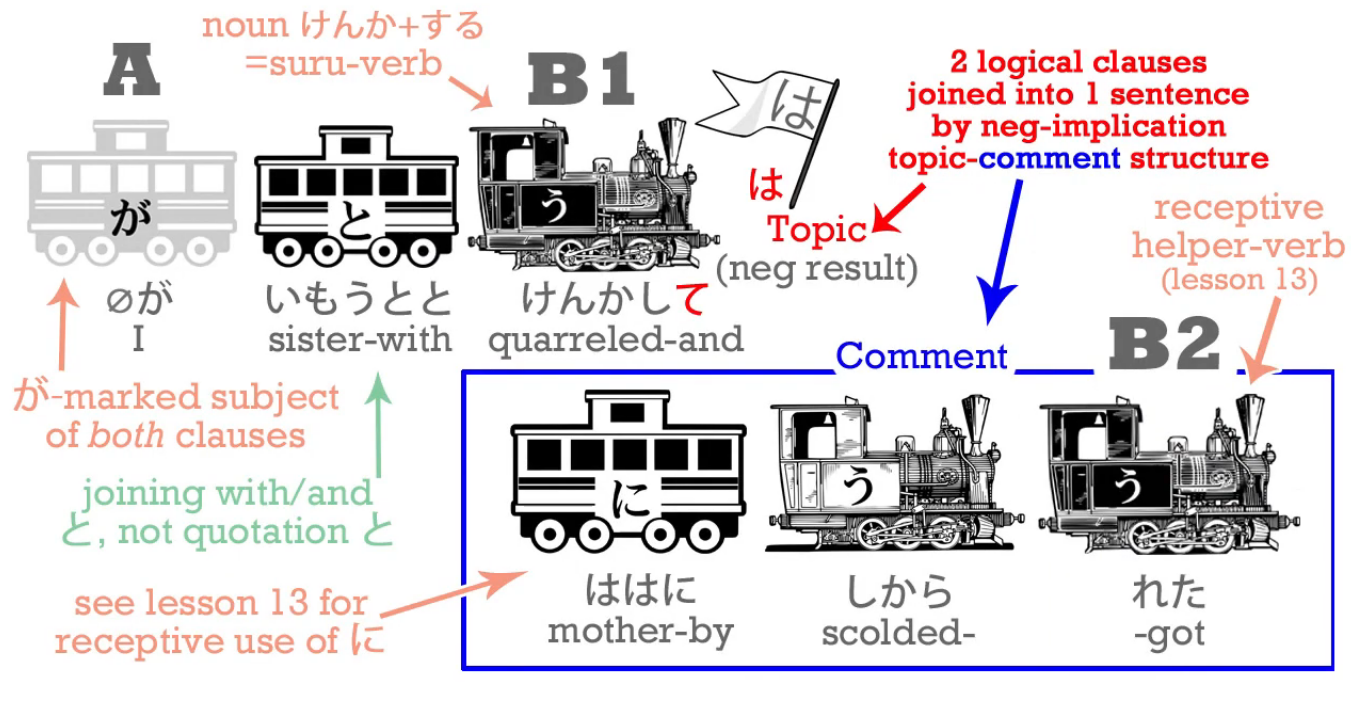

(zero が) 妹とけんかしては母にしかられた

– Because (I) quarrelled with my sister, I got scolded…

And again, the は in there indicates that this is a negative result.

So it links two complete clauses with the indication that

the second one follows as an unfortunate result from the first one.

So this is a continuation of the negative implication of -ては.

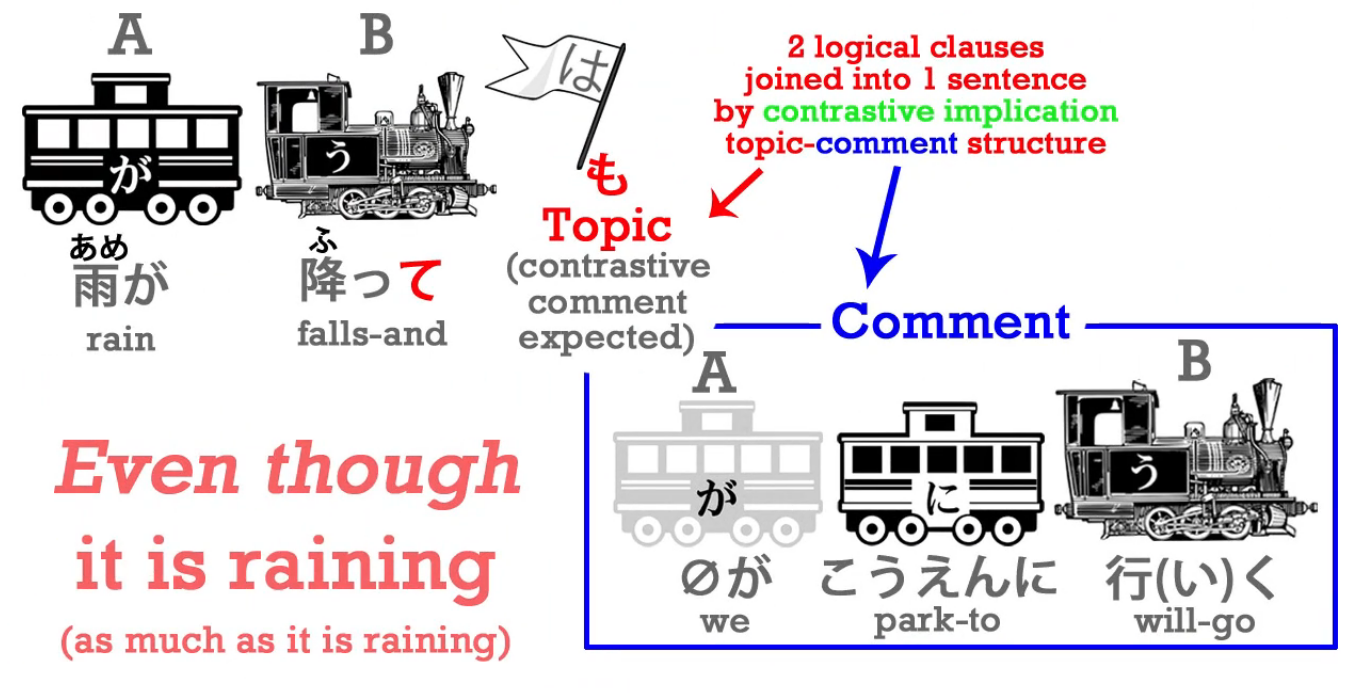

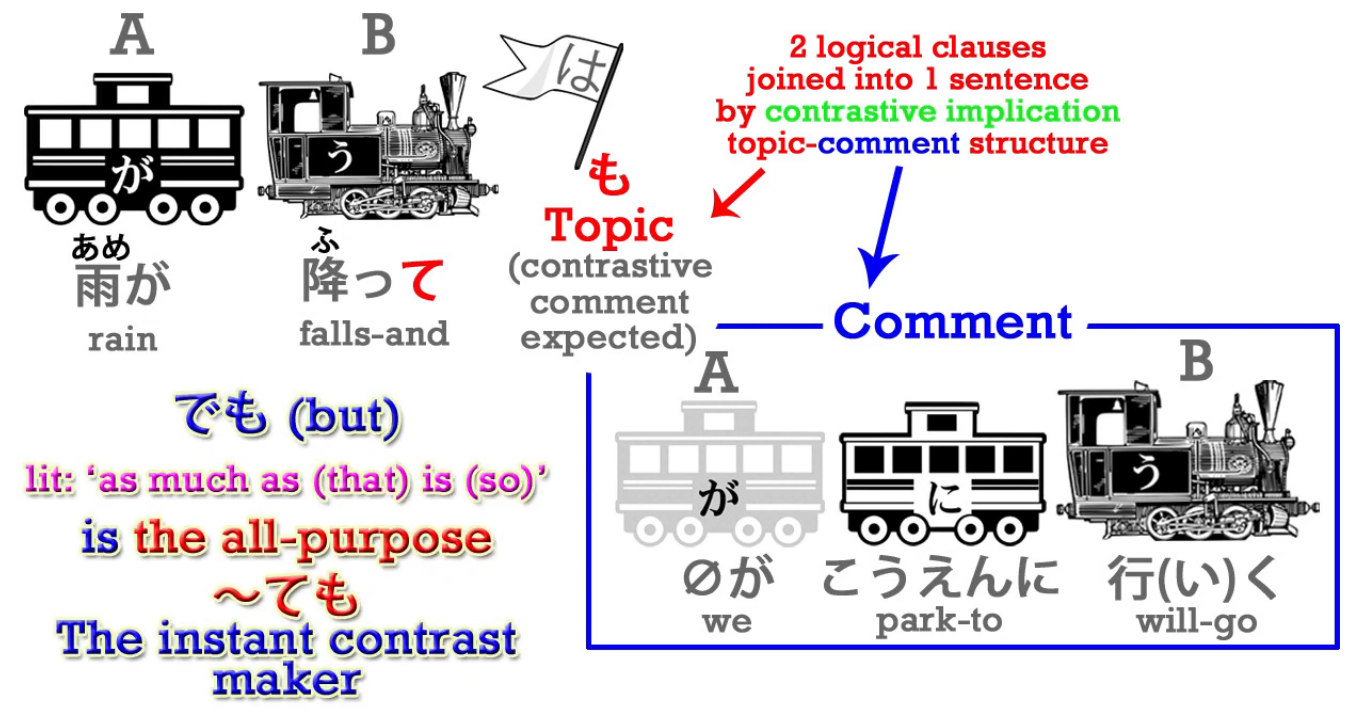

ても / でも as a connector

-ても, on the other hand, when it links two sentences,

doesn’t indicate a negative result or a positive result.

It indicates an unexpected or contrasting result to the first.

So if we said, 雨が降っても公園に行く, we’re saying

Even though*/As much as* it is raining, we’re going to the park.

And you can see that this is essentially the same function as でも,

which gets translated as but, quite correctly.

でも folds up whatever went before it into that で, which is the て-form of だ.

So we’re saying that all happened and the も then adds to it the but element,

the even though, as much as element.

So we could also say, 雨が降るでも公園に行く,

which means almost exactly the same as 雨が降っても公園に行く.

The difference structurally is that in 雨が降っても, the -ても only attaches to 降る,

whereas in 雨が降るでも the で is wrapping up the whole of the last sentence.

In practice that gives us pretty much the same meaning.

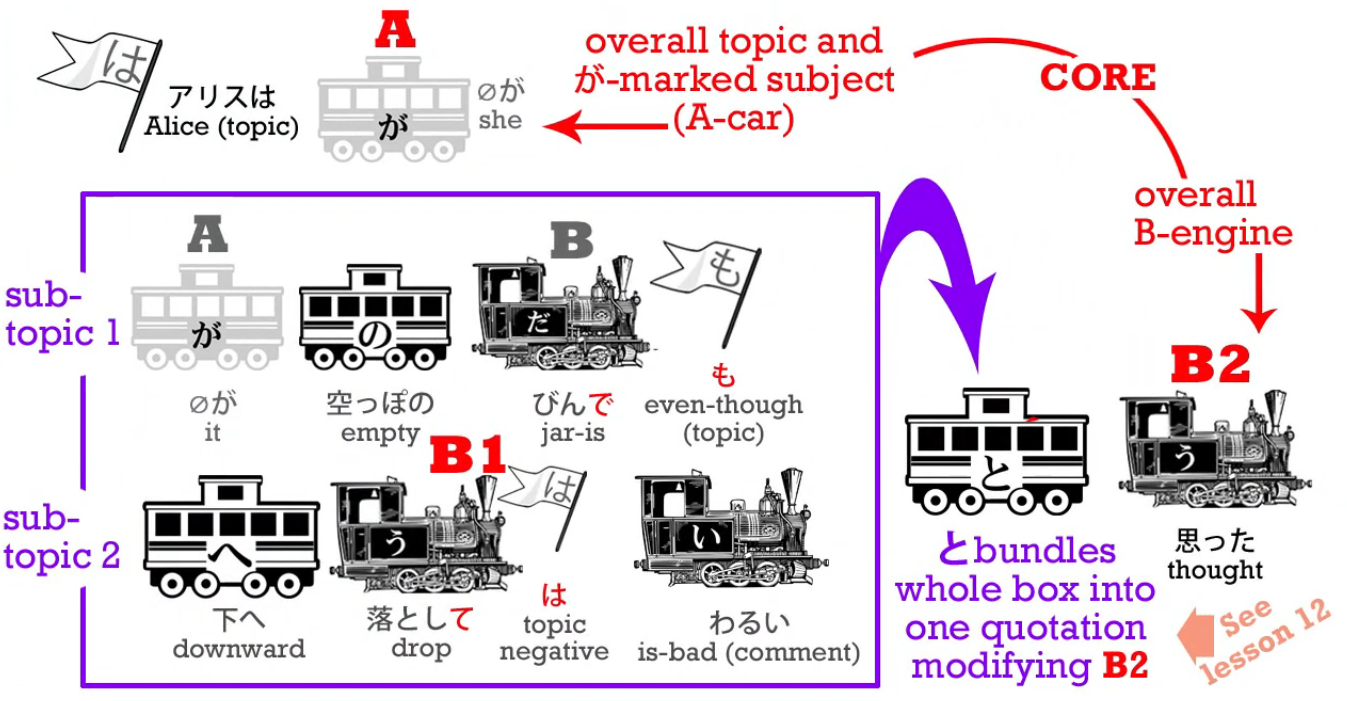

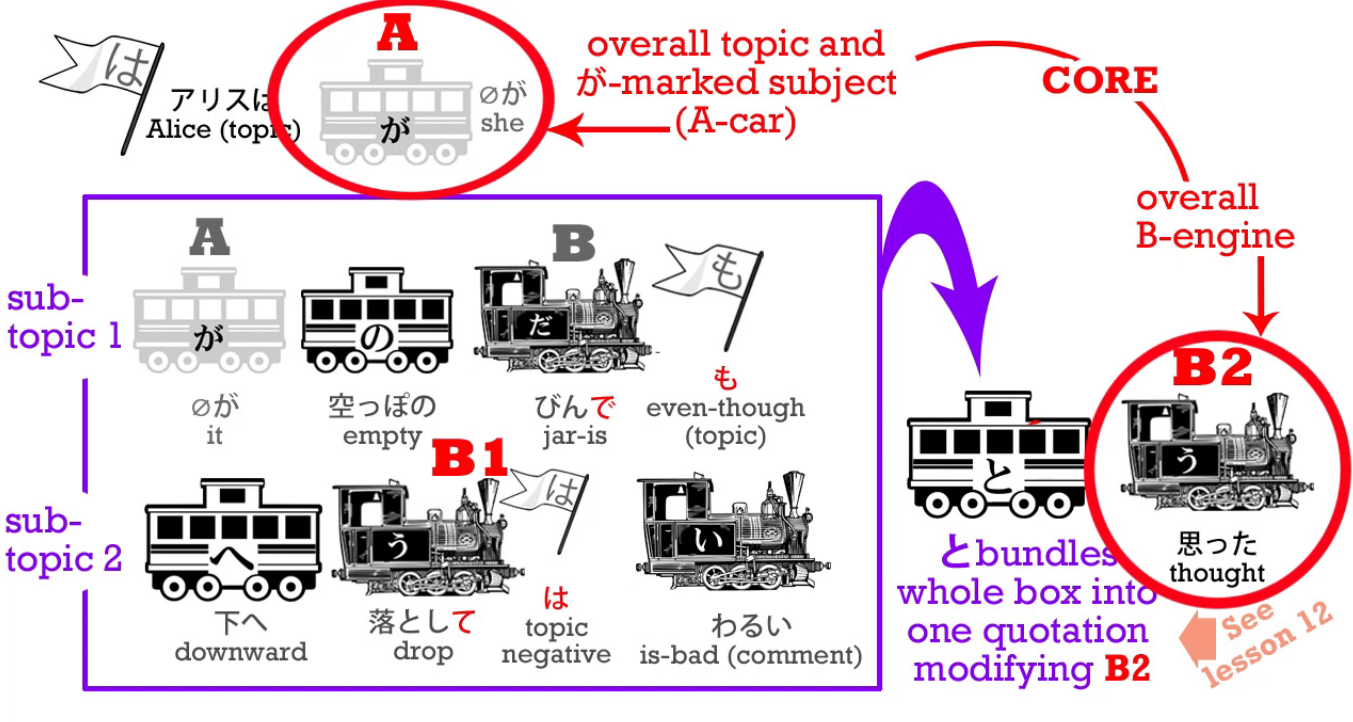

So let’s just go back to that sentence in Alice and see how it’s structured.

It’s a little more complex than it looks at first, but it’s very easy to understand.

And if we can understand it it gives us the key to analyzing much more complex sentences

which could give us trouble in the future.

The core of the sentence is at the beginning and the end.

The whole sentence is just telling us what Alice thought.

So the core is アリスは(zero が)思った.

The inside of the sentence consists of two topic-comment structures.

The first topic is even though it’s an empty bottle (topic) - (zero が)空っぽのびんでも

and the comment on that is itself another topic-comment structure:

as for dropping it, that would be bad - 下へ落としてはわるい

And then the whole of this double topic-comment structure is bundled up into that -と, which really means we can treat the whole thing as a kind of quasi-noun – just bundle up

into that -と and attribute it to Alice as her thought. (思った)

Now, of course, as we’re actually reading or looking at Japanese we don’t think of

as for or speaking of every time we see a topic-comment statement, because as for

in English is much weightier, much more cumbersome than the simple は and も in Japanese.

So what do we do?

Once again, as always, we don’t translate it into English except when we absolutely need to, to explain it or understand it.

We take the Japanese as it is in itself, and that’s how we learn Japanese as opposed to just learning about Japanese.