Lesson 35: Yori, no hou, ippou- how they MAKE SENSE!

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about より and ほう.

Now, より and ほう are often introduced together in sentences like:

メアリよりさくらのほうがきれいだ.

And that is a slightly verbose way of saying Sakura is prettier than Mary.

I think this is an unfortunate way of introducing the two terms because it can easily give rise to confusion.

It can be difficult to understand what term is doing what and how they relate to the rest of the sentence.

It’s much easier if we look at these two separate and independent terms,

both important in its own right, separately, and then we can put them together.

So let’s start by looking at より.

より

より is a particle.

It’s not one of our logical particles, so it does not have to be attached to a noun.

It can go after just about anything: a complete logical sentence, a noun, an adjective, a verb — whatever we want.

Its basic physical meaning is from.

When we send a letter, we may say さくらより — from Sakura.

And abstract words all have their base in physical metaphors, even if we sometimes forget

the physical metaphor, and with words like this, it’s useful to begin by understanding

the original literal meaning and then seeing how the metaphor works.

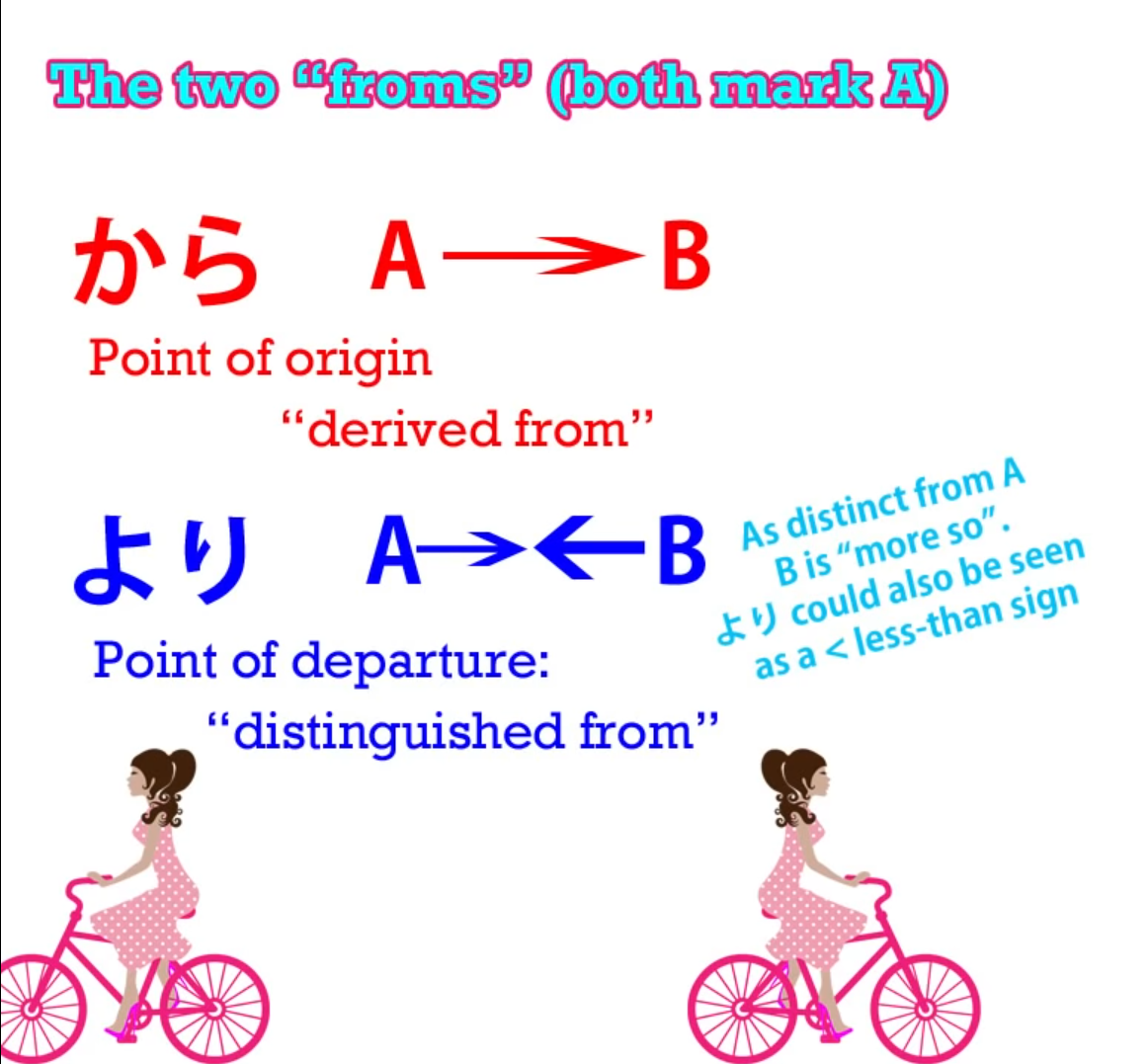

So yori means from, and we already have another word meaning from, don’t we?

And that’s から.

Now, there is a difference between the two, which is particularly pronounced as we start

to apply them metaphorically.

から marks the A in A from B in such a way that it is treating A as the starting point or point of origin.

So, if I say 日本から来ました, I’m saying I came (or come) from Japan / Japan is my point of origin.

And this in a way is midway between the literal, physical meaning and the metaphorical meaning, because it can mean literally I just came on a plane from Japan or it can imply that

I’m Japanese or that I was raised in Japan or something like that.

When we move to its purely metaphorical meaning, it usually means because.

In other words, A is the point of origin of B.

寒いからコートを着る — Because (it’s) cold, I wear a coat /

From the fact that (it’s) cold, I’m wearing a coat.

Now, より means from in a very different sense.

The directional metaphor is concentrating not on the origin of A from B, but in the

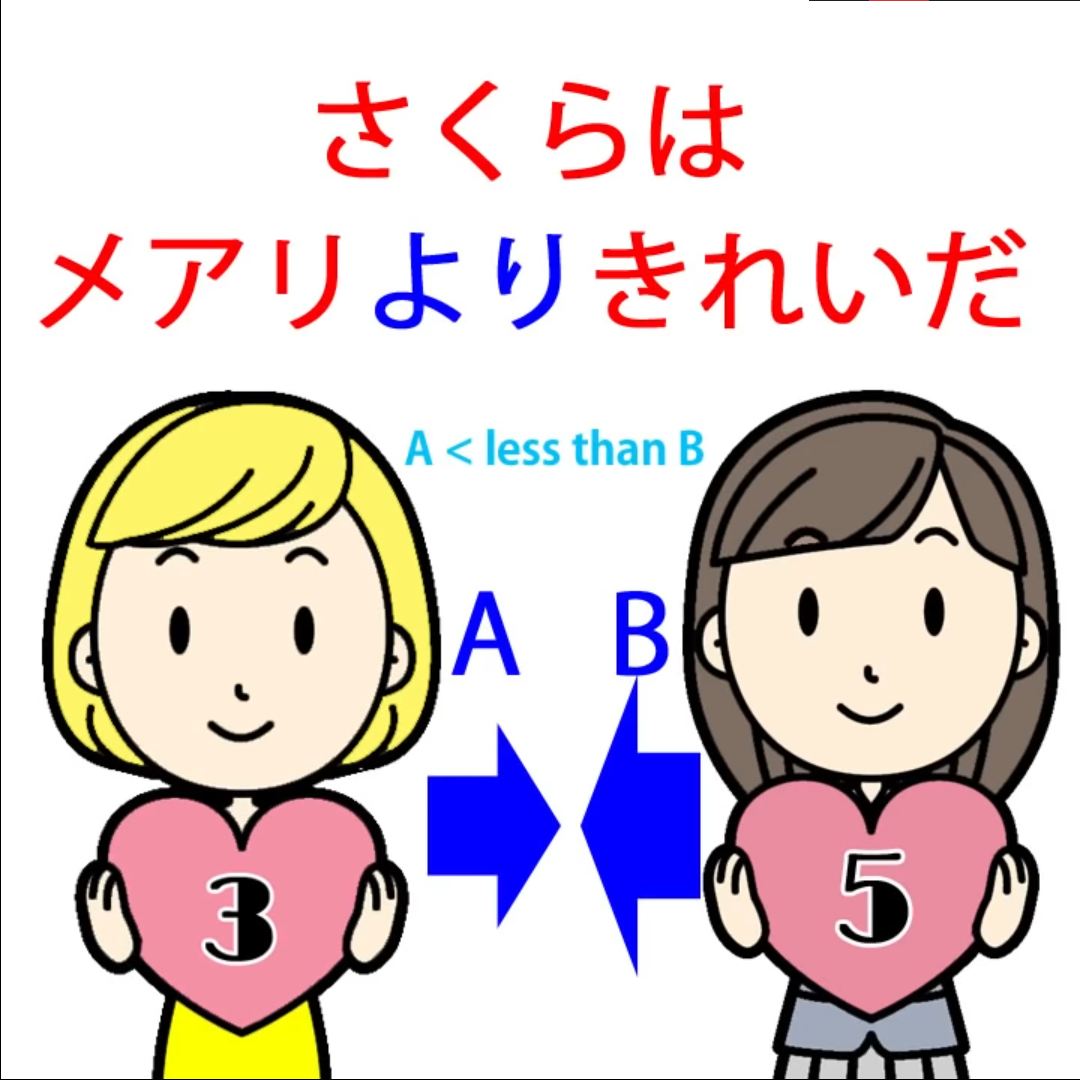

distance or difference of A from B. So, if we say さくらはメアリよりきれいだ

we’re saying that from Mary Sakura is pretty.

What we mean by this is that distinguished from Mary, Sakura is pretty.

Now, it does have something in common with から because we’re still using Mary as the base point, the point of comparison.

And because of this, because it has a comparative meaning, we’re not saying Sakura is pretty but Mary isn’t.

We’re saying that, taking Mary as the point of comparison,

Sakura is pretty — therefore, more pretty, prettier.

In comparison to Mary, going from Mary, Sakura is pretty.

And you notice here that we said just what that first sentence,

メアリよりさくらのほうがきれいだ, was saying and we didn’t need ほう.

It works perfectly well to say exactly the same thing without that ほう.

And we use より in other contexts.

For example, we may say 今年の冬はいつもより寒い, which literally means

Comparing from always, this year’s winter is cold or This year’s winter is colder than always.

And what that actually means is This year’s winter is colder than usual, colder than most other years.

So that always is a kind of hyperbole, in a way.

Similarly, we can say さくらは人より賢い(かしこい) — Sakura is clever compared to people.

And what that means, again, is “Sakura is clever compared to most people / Sakura is

clever compared to people in general — in other words, is cleverer than” the average person.

All right, so now let’s look at ほう.

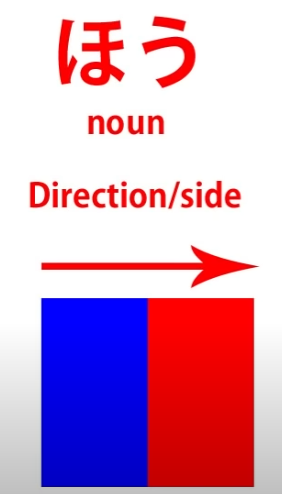

ほう

ほう is quite different.

It’s not a particle, it’s a noun.

That’s why we have のほう.

And its literal meaning is a direction or a side.

And when we say side, we mean side in the sense of direction,

not in the sense of edge.

So, for example, if we talk about two sides of a field with ほう, we’re not meaning the

two edges of the field, we’re meaning that we divide it approximately in half

and we talk about the left side and the right side of the field.

Now, as we see from this analogy, one side always implies the other side.

And that’s the important thing about ほう in its metaphorical uses.

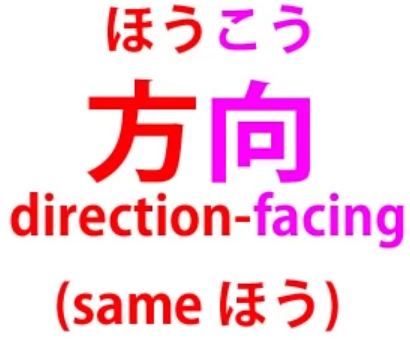

In its literal use, when I’m cycling in Japan, I might say to a stranger,

pointing in the direction I’m going in, それは本町の方向ですか?

And that’s saying Is that the direction of Honmachi?

I’m not asking for street directions, which I can’t understand in English, or Japanese,

or any other language.

I’m asking for the literal direction: Is Honmachi that way, or am I going in the opposite direction? – which I often am, because I am 方向音痴 / ほうこうおんち, which means (I) have no sense of direction.

So when we apply it metaphorically, we mean one thing or circumstance or whatever as opposed to another.

We can put it after a noun with の, as we do with Sakura: さくらのほう,

or we can put it after a verb or an adjective, in which case that verb or adjective is describing the ほう, telling us what kind of a ほう it is, which side it is.

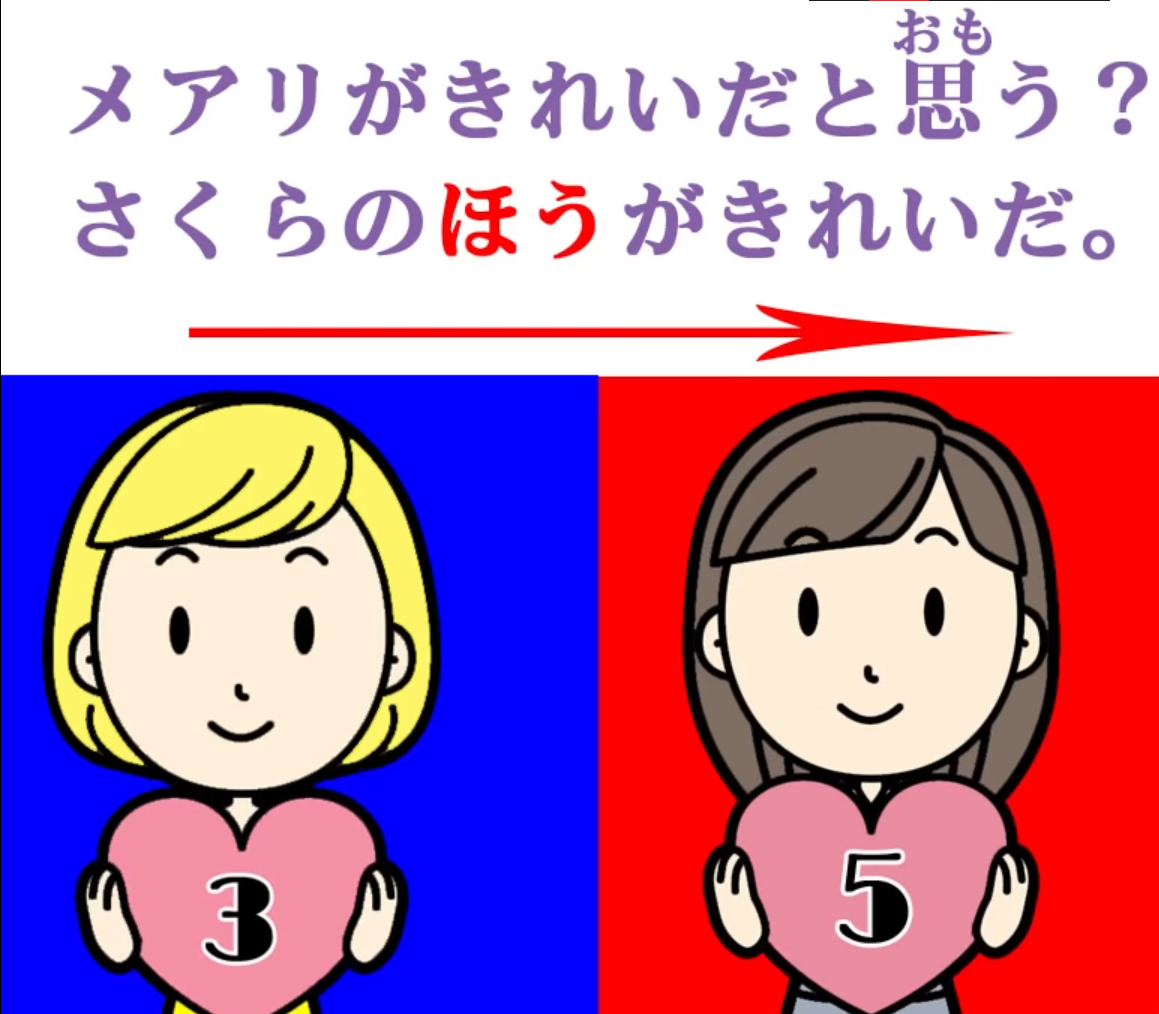

So, if you say to me メアリがきれいだと思う?

— Do you think Mary is pretty? — and I reply さくらのほうがきれいだ, I’m saying

The side of Sakura is pretty — in other words, I think Sakura is prettier.

Once again, it’s a comparative construction, so I’m not saying Sakura is pretty and Mary isn’t, but I am saying that the side of Sakura is prettier than the other side, which is Mary.

And, once again, let’s notice that we don’t need より here.

さくらのほうがきれいだ works perfectly happily on its own to mean exactly the same thing. And a lot of the time you’re going to see either より or のほう on their own.

We do sometimes use the two together and when we’re doing that we’re either speaking fairly formally or we’re really trying to underline the point of the difference and comparison between the two.

一方 (いっぽう)

Another case in which we see ほう is in the expression 一方, which means one side.

And we can see this often used in narrative, sometimes right at the beginning of a sentence — not just a sentence, but a paragraph, and indeed a whole section of the story.

And what it’s doing when we do this is it’s saying essentially what we mean in English

when we say meanwhile.

But we shouldn’t say that 一方 means meanwhile, because it doesn’t.

Meanwhile is a time expression. It’s saying at the same time.

一方, while performing the same function, does it quite differently.

What we say when we say 一方 before going into something else, is really referring back to what we were talking about before, whatever that was.

And we’re saying All that was the one side; and now we’re going to look at the other side.

It’s like でも, which wraps up whatever it was went before with で which is the て-form of です – all that was, all that existed — も gives us the contrasting conjunction:

でも — but. And we’ve talked about that in a different video lesson, haven’t we?

::: info

That video is not part of this transcript grammar series, but it is* **this video.*

:::

一方 should probably, strictly speaking, be 一方で; however, because it’s a common expression, as is often the case with common expressions, we are allowed to drop that copula.

So, if we say that King Koopa (that’s Bowser) was completing his preparations for the wedding ceremony with Princess Peach, and then we say 一方 Mario’s jumping up blocks on his way to rescue the princess.

So on the one side, that’s what’s happening with Bowser in Bowser Castle;

on the other side, this is what’s happening with Mario in the Mushroom Kingdom.

We can also use 一方 as a conjunction.

And essentially this is working just the same way as the 一方 which means meanwhile.

It’s taking one side, and then the other side, so it’s a contrastive conjunction.

So we might say この辺りは静かな一方で不便だ — “It’s quiet around here, but

it’s inconvenient / on the one hand, it’s quiet around here, but it’s inconvenient.”

Literally that この辺りは静かな (which of course is 静かだ in its connective form)

.. this area is quiet — and all that is a descriptor for 一方: 静かな一方.

One side is that around here is quiet.

So, we’re describing the one side, the 一方で and then で, that’s the copula —

One side is that it’s quiet, and the other side is… (but we don’t actually say “but the

other side is, that’s already implied) — One side is that it’s quiet, it’s inconvenient.”

And that 一方で acts as the conjunction.

And we can, once again, leave off the copula here.

One other use of 一方 that we should mention is that it can also be used after a complete

verbal clause to show that something that is happening is continuing in one direction.

For example, we might say この村の人口が減る一方だ — “This village’s population

is just declining and declining / … just goes on declining.”

この村の人口が減る means This village’s population is declining

and the 一方 is telling us that it just continues on in that one direction: it never grows,

it never stays still, it just declines and declines.