De-aru and the Structure of Japanese. What older copulas tell us: である, であります、でござる、でございます | Lesson 84

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk again about that element of Japanese

that gives us the key to about a third of all Japanese sentences,

and that is the copula.

::: info Notice how copula LINKS together the A (Subject) and B (Predicate), that is its function. ::: Now, I’ve talked quite a bit about the copula before

and I’ll put links in the information section below

so that you can follow that up. (Lesson 40, 41, 55, 77 & 79 I think…)

But today I want to look at slightly less commonly used versions of the copula

which you are going to see quite a bit in your immersion

and that raise certain questions about the structure of the copula itself

which we’re going to address.

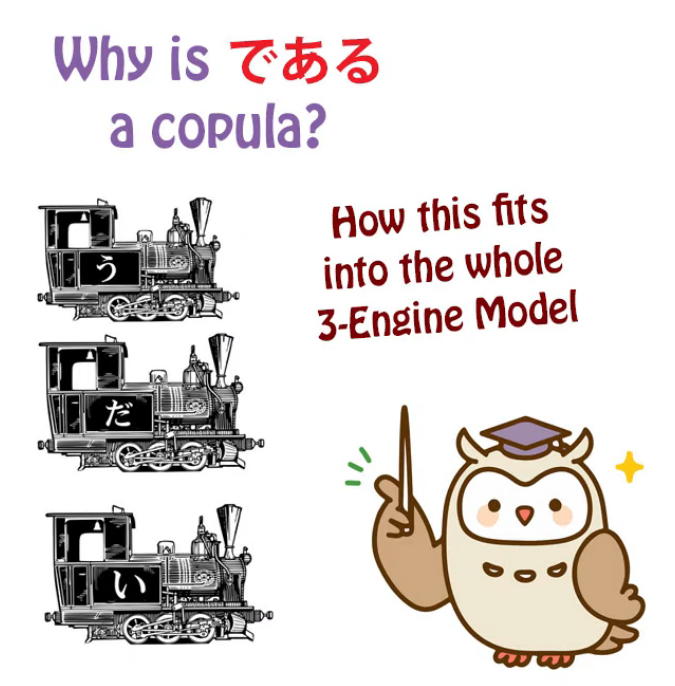

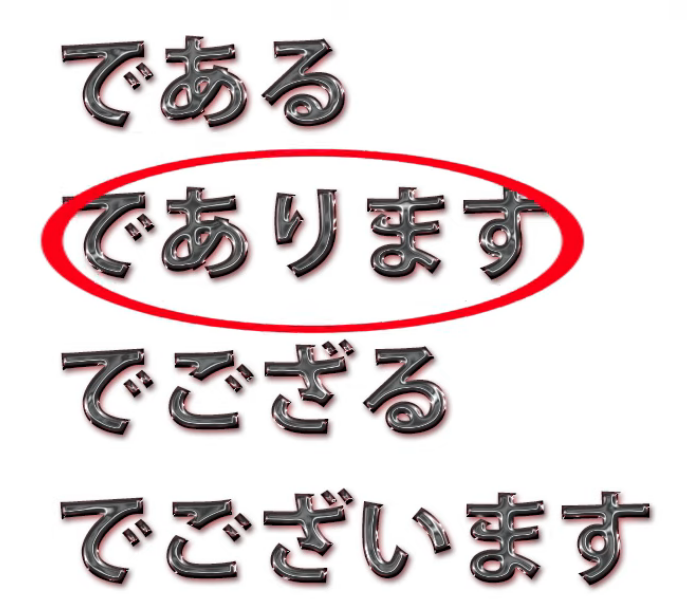

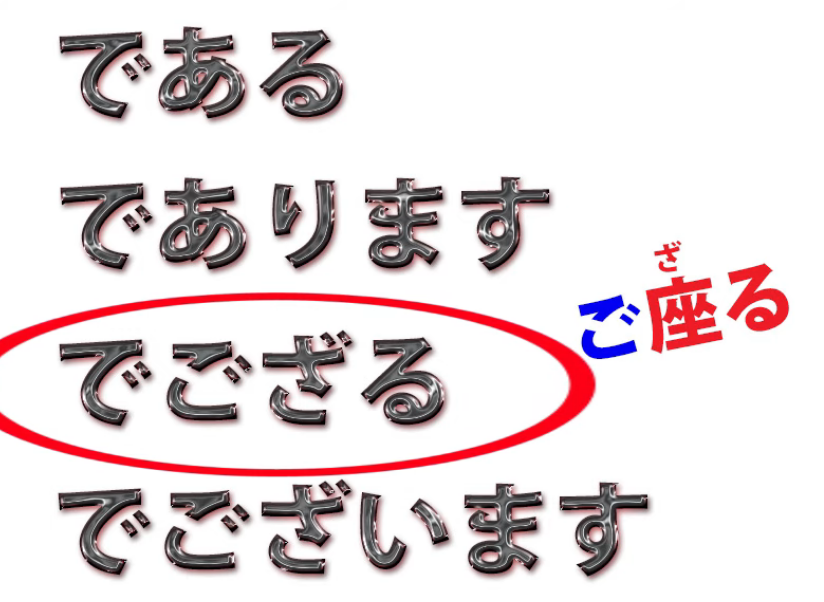

These are: である, であります, でございます and でござる.

Now, we can deal with the last three very quickly,

because all of them are just variants of the first one, である.

であります

であります is obviously である with the ます helper verb attached.

でござる

でござる — ござる is simply a polite, keigo version of ある, the verb of being.

Now, how does the verb of being get into this?

Well, we’ll talk about that in a minute.

ござる is simply made up of the honorific ご plus ざる / 座る,

which originally means seated, but has the extended meaning of existing.

::: info

座る is normally read as すわる, but its On-yomi reading is ざ, therefore ざる here because I guess it is referring to its extended meaning of existing?

:::

So ござる / ご座る is just ある in fancy form.

You won’t hear でござる very much at all because since it’s an honorific form

these days it’s nearly always used with the ます helper verb attached.

But you will hear ござる perhaps in period drama and things like that.

It’s samurai talk.

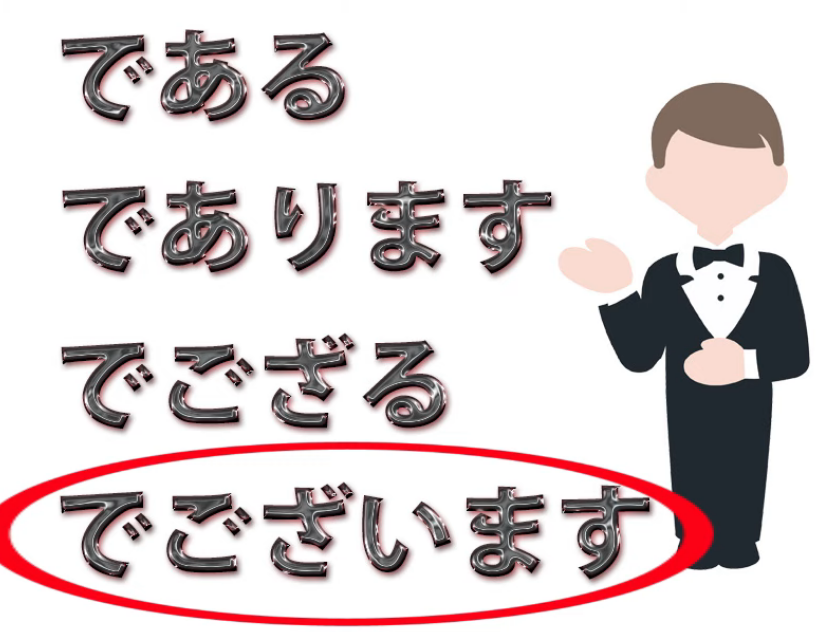

でございます

でございます is the form of the copula that’s used in keigo,

so you’ll hear it in shops, you’ll hear it in public announcements,

and you’ll hear it used by speakers in anime etc who are using very honorific speech,

perhaps sub-villains talking to the main villain.

So that’s really all we need to say about those three.

である

But である, which is the root of all of them, is the one we need to pay attention to.

You could call it, in a way, the straight copula.

だ sounds casual, です is polite, but である is just the copula.

We see it used in contexts where we’re simply being objective,

such as academic papers, newspaper reporting, that kind of thing.

We’ll also see it used in other contexts regardless of

what register the writing is in because it has a particular quality.

As we know, だ and です can only be used at the end of a logical clause.

They are logical-clause endings and they can’t be used to pre-modify a noun.

If we want to pre-modify a noun with another noun marked by the copula,

we can only do that if it’s an adjectival noun, because adjectival nouns

can use the pre-modifying version of the copula, which is な.

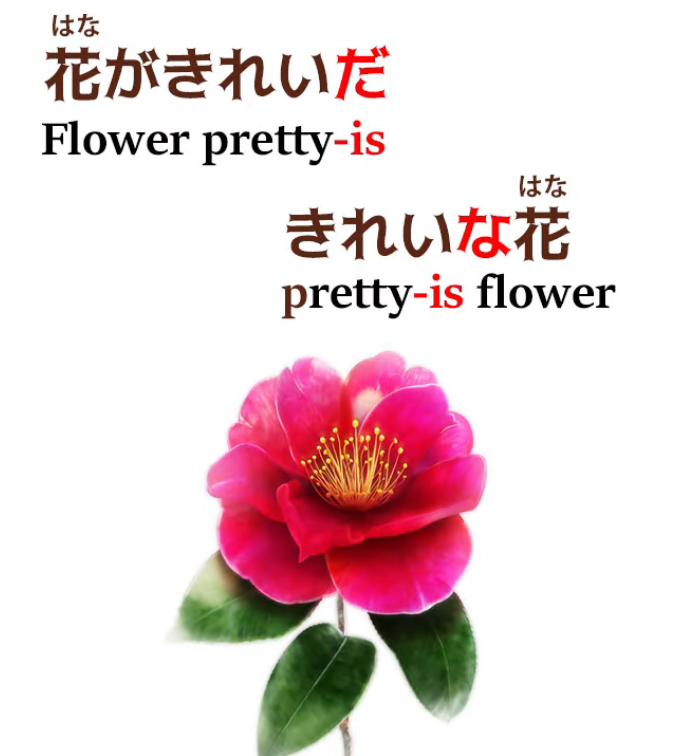

We can say 花が綺麗だ (flower pretty-is)

or we can say 綺麗な花 (pretty-is flower).

And it’s precisely because this group of nouns —

and I’ve talked about the three groups of special nouns

in another video if you’d like to look at that (Lesson 41) —

this particular special group of nouns, adjectival nouns, has the property

that it’s able to use the pre-modifying form of the copula, な.

This is something that the textbooks don’t seem to know.

They don’t tell you what な is and they tell you that adjectival nouns

are actually some weird thing called な-adjectives.

But that’s another matter.

So what do we do if we want to use a copula-marked noun

as a pre-modifier and it isn’t an adjectival noun?

Now, we don’t do this an awful lot because

we can work around the situation by using の.

But in some cases either this doesn’t work

or it just isn’t what we want to do.

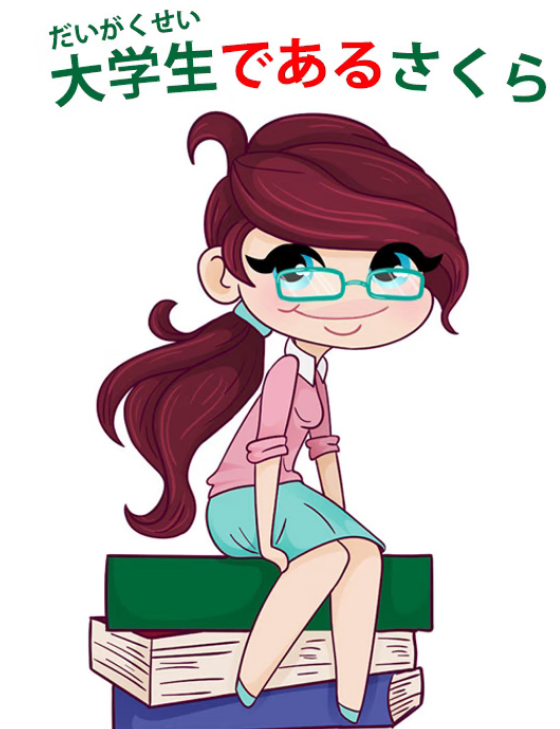

So, suppose we want to say Sakura who is a university student.

Now, we can say 大学生のさくら, which is the university student Sakura.

But suppose we don’t want to say that.

Suppose we actually want to say Sakura who is a university student? (make a relative clause)

It’s not quite the same, in Japanese or English.

In order to do this we have to use the copula and

we have to use it as a pre-modifier, so we have to use である.

It’s our only choice. We can’t use だ or です

because they can only be used at the end of a logical clause.

And we can’t use な because 大学生 is not an adjectival noun.

So we say 大学生であるさくら. (Sakura who is a university student)

And you’ll see that sometimes, especially in written material.

But there are cases where you really don’t have the choice at all.

For example, if you want to say the state of being round,

you would say 円形であるさま.

Now, さま is a state or condition.

We can’t really use の here; 円形のさま doesn’t really work.

So we really have to say 円形であるさま.

Now, when I say that である is the straight copula,

not the casual one, not the polite one, just the straightforward copula,

there’s another reason for this,

because ultimately and historically

だ is simply an abbreviation of である

and です is an abbreviation of であります.

So, if you’ve followed my course, if you’ve been

trained up to look at Japanese structurally,

there are certain questions that this may make you want to ask,

and some people have asked me.

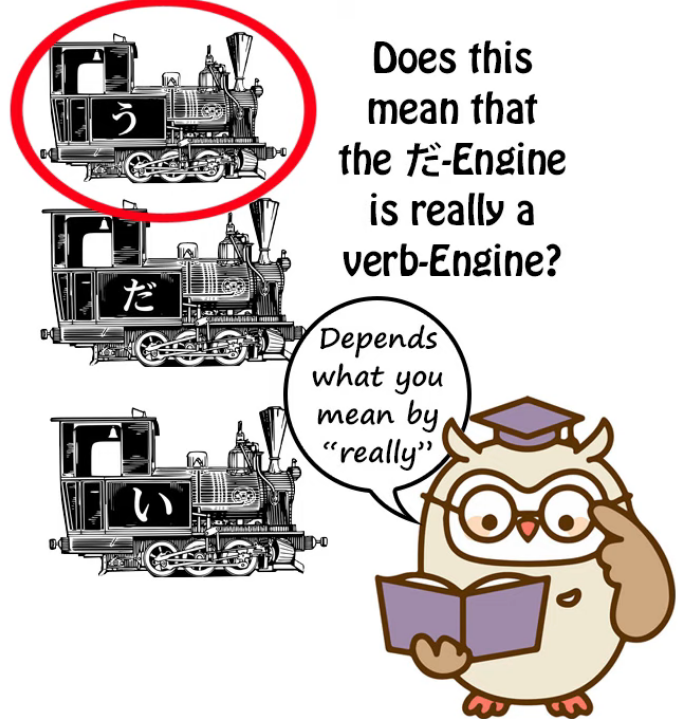

First of all, haven’t I presented the copula as an indivisible, special unit,

one of the three engines, but

here it seems to be made up of two elements,

で and ある, and it looks very much like a verb.

So what’s going on here? And then,

why in any case do the elements で and ある

add up to the concept of the copula?

Why で & ある add up to make copula

Now, let’s look at this second part first and then we’ll look at the first part.

Why do で plus ある make the copula concept?

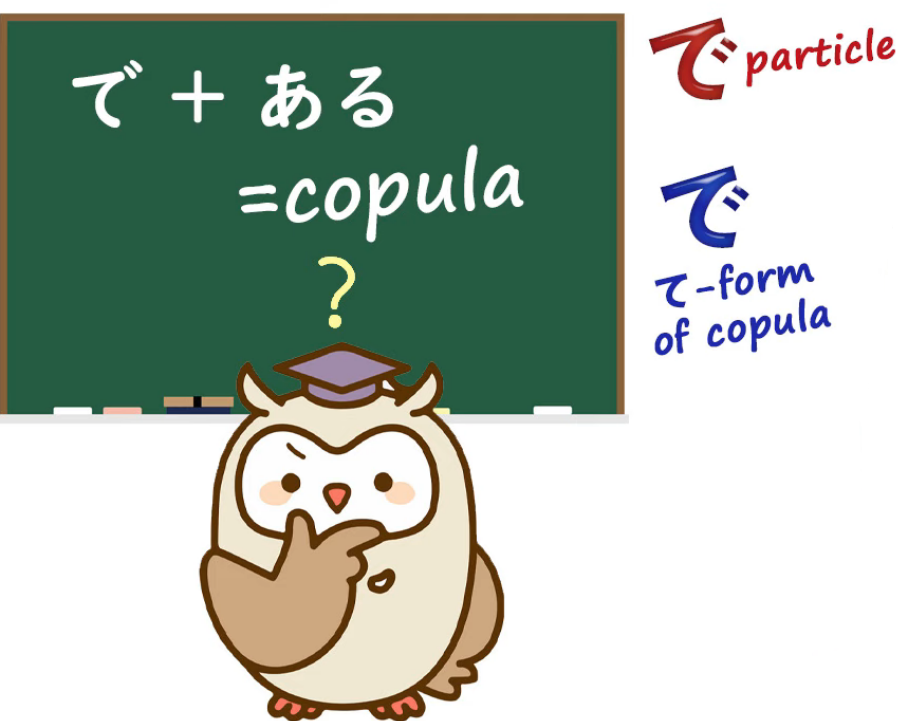

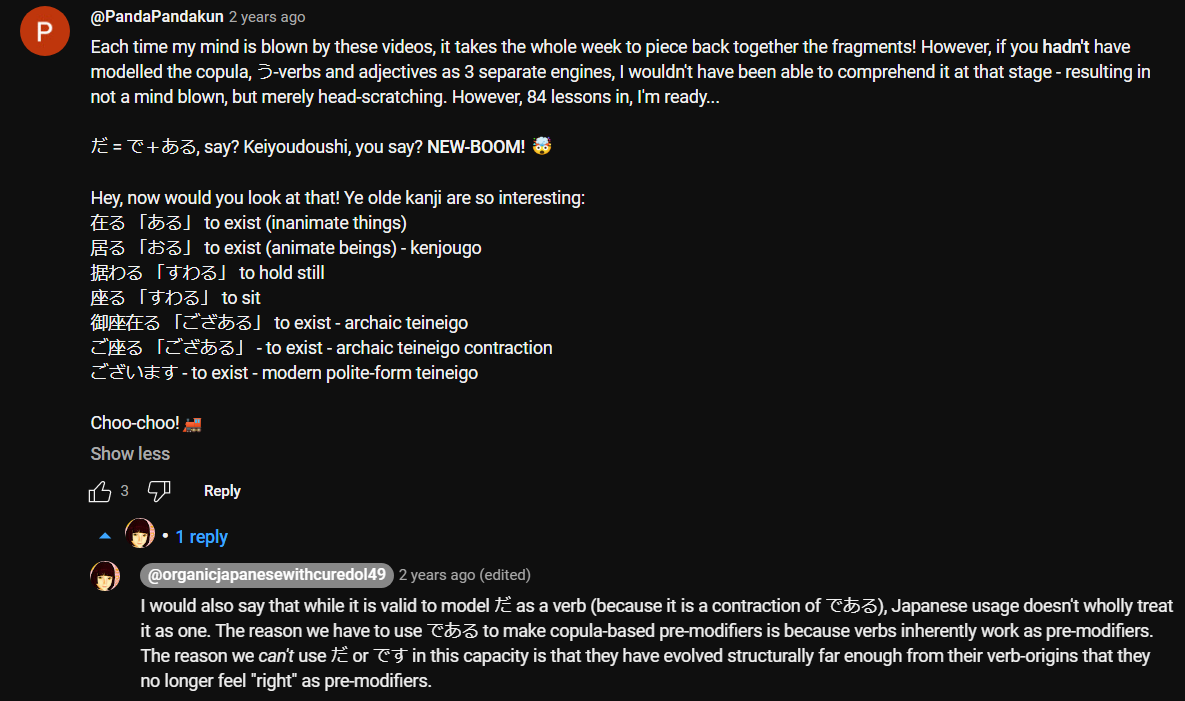

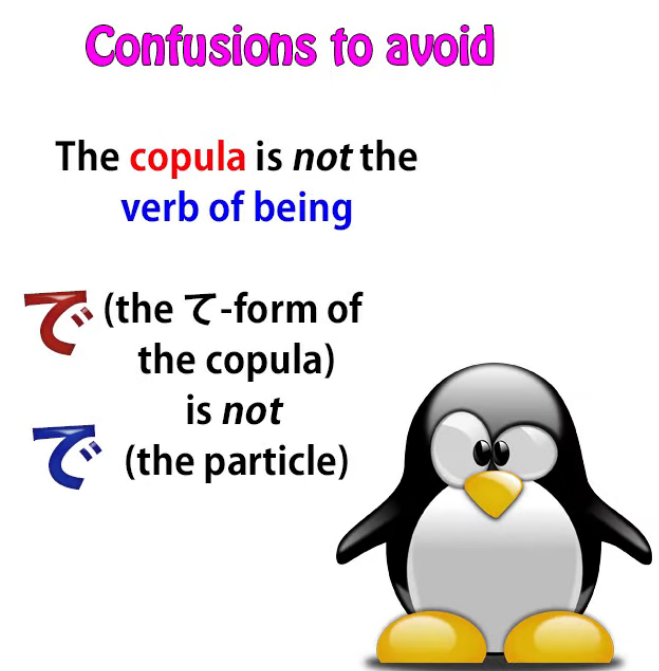

Well, as we know there are two でs in Japanese.

There’s the particle で and then there’s the て-form of the copula.

The textbooks don’t tell you this.

They let you think everything is the particle で.

But as we know there are two でs.

Now, the one we’re dealing with here is obviously the particle で.

::: info Huh…funny that this で particle thing was also one of my theories about である (and だ) ::: It can’t be the て-form of the copula because the fundamental copula

can’t be made up of two elements, one of which is already the て-form of itself.

And in order to understand what’s going on here,

why で and ある add up to the copula, we need to know two things.

Now, I’ve made videos on both of these and I’ll link them as well,

but let’s just recap it here.

::: info

it’s a bit hard to say which videos Dolly meant, but if so review Lessons 40, 41, 55 and 79.

:::

The two things we need to know are first of all what the copula actually is,

and the second is what the particle で actually does.

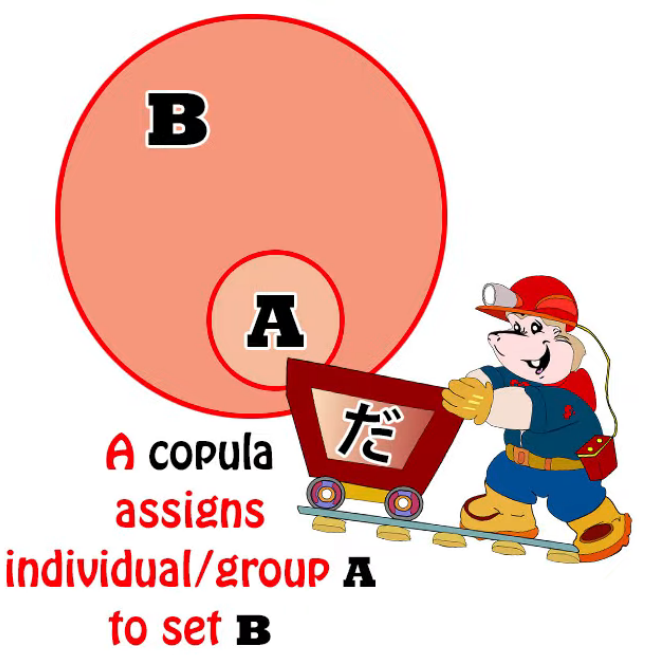

What the copula actually is / does

What the copula actually is is something that takes two nouns, A and B,

and tells us that noun A is part of a set represented by noun B.

That’s what the copula does. That’s all it does.

So if we say さくらが日本人だ

we’re saying Sakura (noun A) is part of the set Japanese people (noun B).

And sometimes the set can be a set of one.

So if we say That person over there is Sakura, then we’re saying that

that person over there belongs to the set of one which is Sakura.

We’re not talking about other Sakuras.

We’re talking about this particular Sakura.

What the particle で is / does

So now, what does the particle で actually do?

I’ve made a video about that and I’ll link it. (Lesson 55)

Fundamentally the particle で defines the limit or field or parameter

within which an action takes place or a state of being prevails.

So the simplest use of で is to say where an action takes place:

公園で遊ぶ (play in the park) —

the park, which is marked by で, is the field, the area, the parameters, within which I play;

世界で一番おいしいラーメン (the most delicious ramen in the world) —

the world marked by で marks the field, the area

within which this ramen is the first, number one.

And it gets extended a bit further in other cases.

It could be the material something’s made with, the tool something is made by, etc.

In all cases it singles out a particular parameter from other parameters

that allow the making to take place.

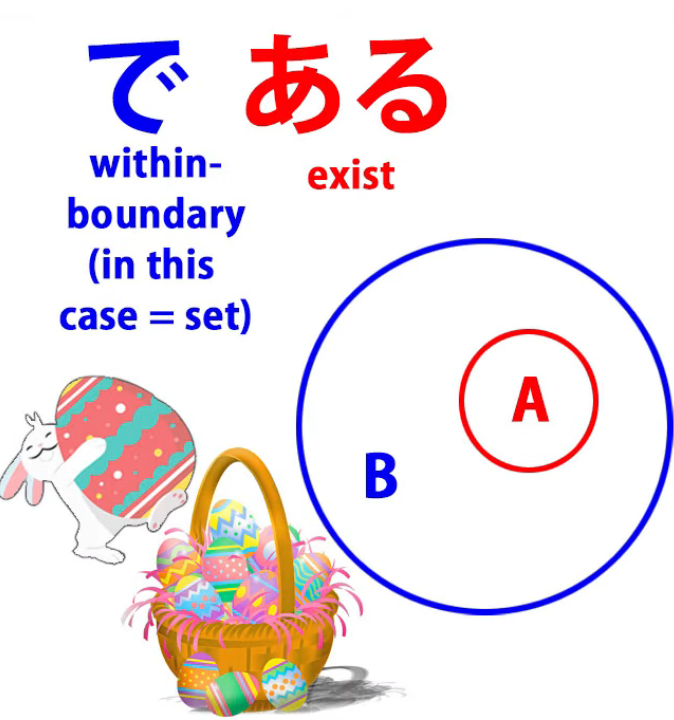

Back to である

Now, when we take である, what this is saying is

exist (ある) within a particular boundary or parameter;

in other words, exist within a set.

And that’s what the copula tells us.

It tells us what set, what boundary, something exists in.

Sakura exists within the boundary of Japanese people.

If we say 鷲が鳥だ (an eagle is a bird) we’re saying

an eagle exists within the boundary, within the parameter, within the set, birds.

And this is what the copula always does.

So である is a very precise construction of the copula.

So let’s get to the second question.

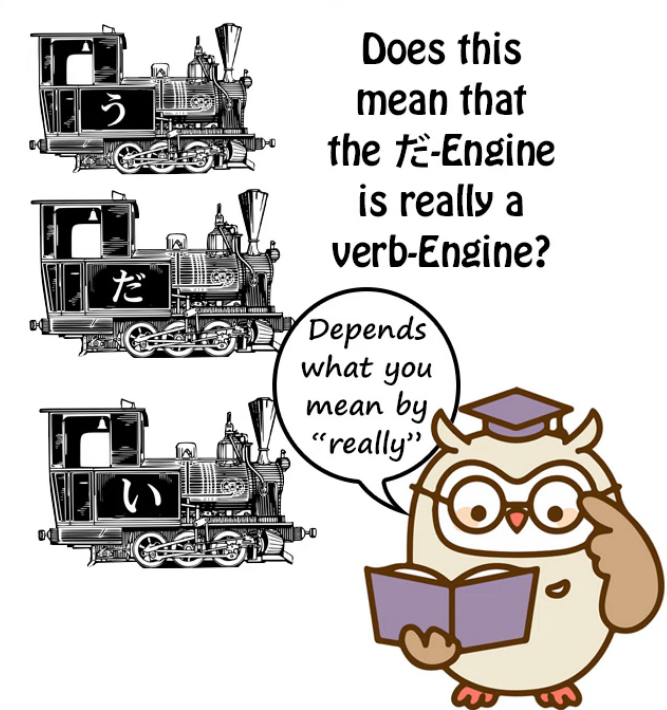

Is である / the copula a verb?

The second question is, does this mean that it isn’t really

an indivisible element of Japanese, one of the three engines?

And does it mean that it’s a verb?

Because obviously ある is a verb, and it’s because

ある is a verb that we can use it as a pre-modifier.

We can say 大学生であるさくら because

you can always use a verb to pre-modify a noun.

And the answer to the question is that this is a question of modeling.

I model Japanese in a particular manner.

It is possible to model it in other manners.

In Japanese grammar as taught to Japanese students, the copula is regarded as a verb.

(thus, copula has a verbal function = it can theoretically be regarded as a special kind of verb)

And in fact an adjectival noun plus the copula is called a 形容動詞,

which means an adjectival verb.

The verb part is the copula which is added to it.

So 綺麗 is not a 形容動詞; 綺麗な or 綺麗だ is a 形容動詞.

And the 動詞 part, the verb part, is the copula.

But I do not model the copula as a verb.

And the reason for that is that in our three-engine structure

I restrict the term verb to those entities that end in う-row kana

and do all the things that those entities do: we have the four stems, etc.

::: info This further shows that there are different ways to view language, and both can work in their own systems, so it is best to be aware of both ways & use them as what works for you. ::: The copula doesn’t work like this in modern Japanese. It works differently.

である has evolved into an entity in itself with its own て-form,

which it has, with its own connective form, な, which it has.

We could, if we wanted to, model all three engines as verbs,

because in many ways adjectives are also verb-like.

But they don’t work like the う-ending entities and they don’t work like the copula.

So, within my model of Japanese,

which I think is the best one for non-native learners of Japanese to use,

we use the three-engine structure.

We regard verbs, adjectives and the copula as three unique entities.

This is not a statement about the etymology of Japanese.

It’s not even a statement about the real truth of Japanese grammar,

because there is no real truth in grammar.

Grammar is simply a means of describing

a pre-existing phenomenon, which is language.

Grammar is not the source code of language.

Grammar is an attempt to describe language by modeling it.

And I use and recommend the three-engine model.

If you prefer another model, you’re free to use it.

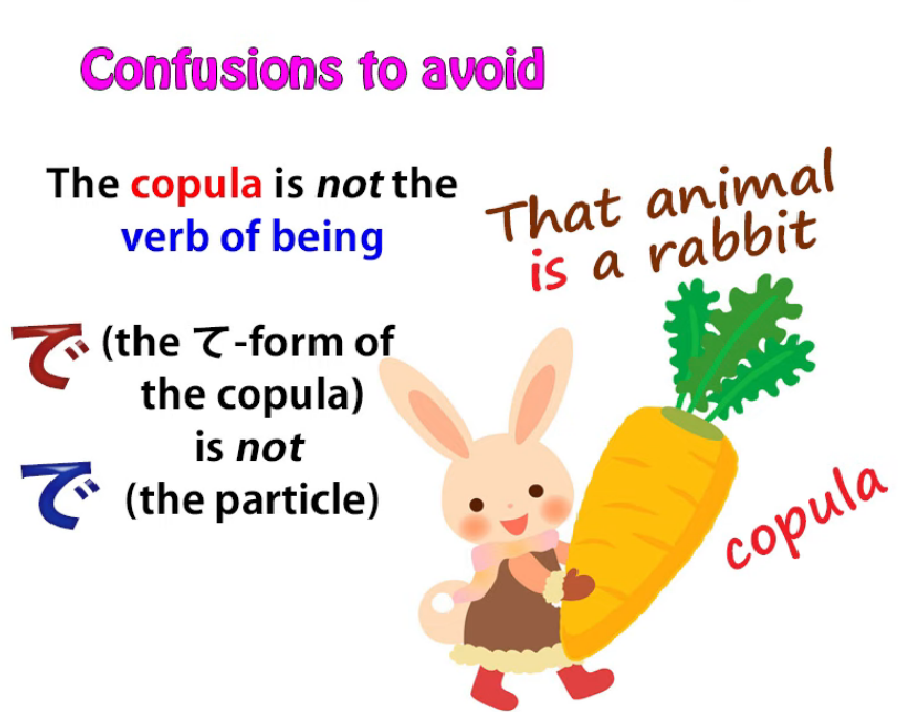

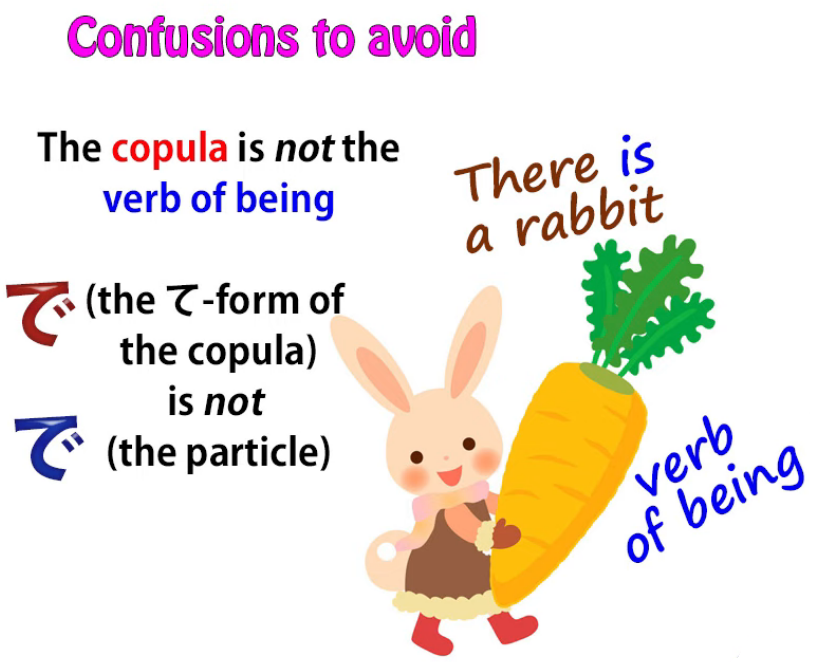

The other reason I maintain that distinction is because it’s very important

not to confuse で which is the て-form of the copula with the particle で,

and it’s very important not to confuse the concept of the copula

with the verb of being, ある.

And that happens all too easily to English speakers

or people who are very familiar with English,

because in English the copula and the verb of being

are represented by the same word,

and that’s is and its variants was, am, are, etc.

They’re the same word, but they’re not the same concept.

So when we say that だ and です mean is,

this is a confusing way of looking at it.

They don’t mean is in all circumstances;

they mean is when it’s the copula.

So if we say That animal is a rabbit, this is the copula.

We’re placing that animal into the set rabbit.

If we say There is a rabbit, that’s not the copula, it’s the verb of being.

We’re saying a rabbit exists, there in that place.

Now, because these two concepts are very easily confusable,

and because textbooks and even more advanced academic texts

do a very, very poor job of differentiating them,

I believe it’s important to keep the copula, which is

an unfamiliar concept in English, because English has no dedicated copula,

**to keep it separate in the three-engine model.

::: info

This is quite interesting, **link here** if the screenshot is too hard to read. Highly recommend reading the entire comment section under this video, as there are some interesting comments.

:::