Why textbook grammar points are so misleading. Basic word-confusion | まま mama | Lesson 42

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about some of the ways in which the standard conventional explanations of Japanese lead you out into the desert and then fly away in a helicopter, laughing.

We talked in the earlier lessons in this series about how that happens

in relation to the fundamental structure of the language.

But this also happens at a later stage with the explanation of all kinds of what they call grammar points.

And one of the main causes of this is the fact that they fail to recognize what words actually are and what they actually do.

So, we’re going to take, as an example, まま, the word ママ.

Now, this can mean a mother or the mistress of a bar or a cafe, but we’re talking about

it in the other sense, the more abstract sense, which, if we look at traditional explanations,

they seem to have various opinions on what part of speech it is.

::: info

to avoid confusion, ママ in katakana means mom or mistress of a bar. Whereas まま is what Dolly is going to be talking about. It also has a Kanji form 儘 or 侭, but that is not really used.

So まま ≠ ママ, different things. まま marks unchanged state, ママ means mom/bar mistress…

:::

I’ve even seen it described as a particle, which it certainly isn’t.

And they tell you that it means as it is / as we wish it to be / as we would like it to be,

that it means a state or a condition.

Now, all those things are things that we might say in English in relation to certain uses of the word.

But none of them express what the word actually means.

In any case, if it meant as it is or as we wish it to be, what kind of a word would it be?

So the first thing to ask ourselves is What kind of a word is it?

And, as I explained in our last lesson, nearly all Japanese words fall into one of three categories: nouns, verbs, and adjectives.

Now, まま is not a verb: it doesn’t end in -う or any う-row kana.

It’s not an adjective: doesn’t end in -い.

So the chances are it’s a noun, and that’s exactly what it is. It’s a noun.

So, what kind of a noun is it? What does it mean?

What is a まま? A まま is a thing; it’s a noun. What kind of a thing is it?

Well, it’s a very simple thing, a very straightforward thing, and once we know what it is

we can understand it in all circumstances.

A まま is an unchanged condition.

Wherever you see まま, you can read unchanged condition.

There’s one circumstance in which it has a slightly extended meaning and apart from that

— which is very simple and we’ll come to that shortly —

we have the definition, the understanding of まま: unchanged condition.

So, let’s look at some of the ways in which it’s used.

We can say 自然のままの森 — that’s a forest in its natural (unchanged) state.

自然 is nature and まま is unchanged state or unchanged condition”.

So, 自然のまま is the unchanged condition of nature.

自然のままの森 is the forest in the unchanged condition of nature.

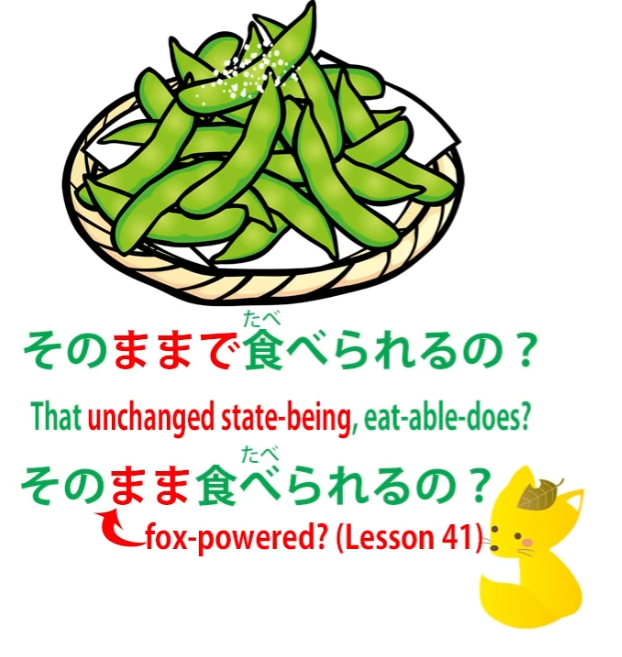

Now, when you’re in Japan somebody may offer you 枝豆/えだまめ,

which are beans which grow from the branches of trees,

which is why they’re called 枝豆 (which means branch bean).

And you might look at them, they’re not cooked or anything,

you might say そのままで食べられるの?

— Can you eat them just as they are / can you eat them in their unchanged condition?

Now, that で is in fact the copula, so we’re saying being their unchanged condition, can we eat them?

Now, there’s one thing we can do with まま that we can’t do with all nouns

and that is that we can drop that で.

So we can say そのまま食べられる?

Now, we can say that this is because まま is something like an adverbial noun

that we discussed last week, where you are allowed to drop the particle in certain cases,

but I don’t think we necessarily even have to go that far.

An unchanged condition is by definition a condition that could change but hasn’t changed.

So, I think in cases like this if we say そのまま食べられる,

we’re saying そのまま食べられる without the で,

I would say, is treating that そのまま like a relative time expression.

We’re saying while they’re in their unchanged condition,

so we’re essentially talking about a time period,

the time period during which they are in their unchanged condition.

So this is actually how I would tend to look at it.

During the period when they’re in their unchanged condition, can we eat them?

In any case, there’s no doubt what the word means.

It means unchanged condition.

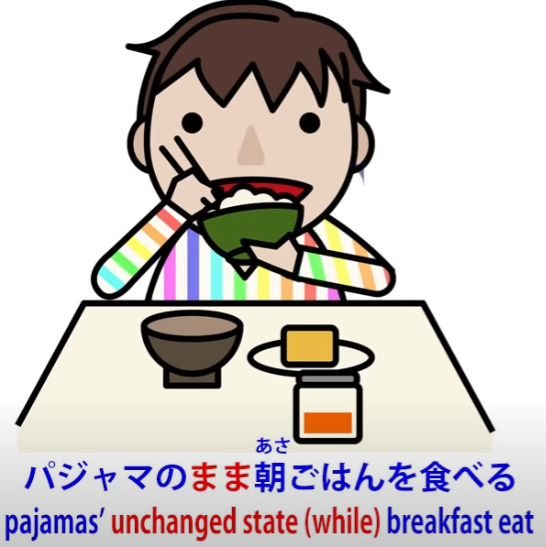

We can say パジャマのまま朝ごはんを食べる.

That means Eat breakfast while we’re still in our pyjamas.

In other words, in the unchanged condition of being still in our pyjamas, eat breakfast.

And as we can see, once again the implication here is that the condition could change but hasn’t changed.

いつまでも若いままでいたい — I’d like to stay young forever.

I’d like to stay in the unchanged condition of being young forever.

And notice here that we’re saying 若いまま,

so you see 若い, the adjective, is doing what adjectives always do, qualifying a noun.

And the noun it’s qualifying is まま: the unchanged condition of being young.

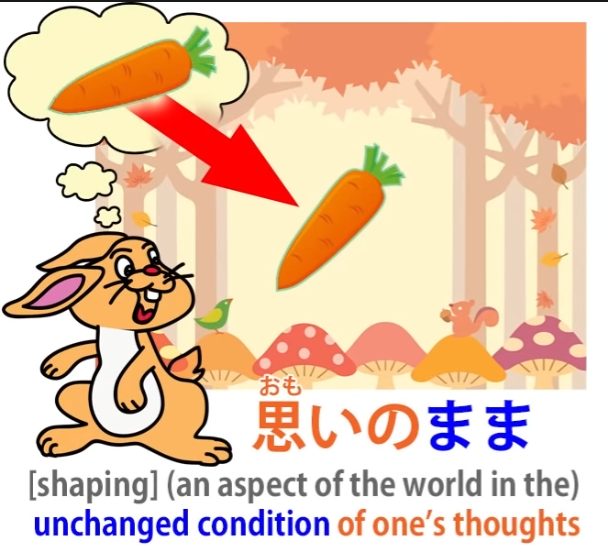

Now, there’s a use of まま that you’ll probably come across quite often,

and that is 思いのまま or 心のまま.

And what this means is in the unchanged condition that’s in our thoughts or …in our hearts.

So what does this actually mean?

Well, it’s always applied to something that is outside ourselves,

so we’re talking about something outside ourselves being in the unchanged condition,

the exact same condition, as what is inside ourselves.

So this essentially means making the outside world conform to our thoughts, our desires, our will.

And this can under certain circumstances imply selfishness, but it doesn’t need to.

I think the first time I heard it was in an anime where the characters were underwater.

They were able to breathe but they found that they couldn’t move the way that they wanted to,

just as one can’t in water.

And they said 思いのままに動けない —

we are unable to move in the unchanged condition of our thoughts

or …the unchanged condition of our will or desire.

Now, we should understand here that 思い sometimes does imply desire.

For example, when we say 片思い, which is literally one-sided thought

or one-side thought, what that actually means is unrequited love.

It means having a desire for someone but it’s only one side of the desire.

The other person doesn’t reciprocate that desire.

So it’s 片思い — one-sided thought or one-sided desire.

So 思いのまま is in the unchanged condition of one’s thought or desire.

And it’s really from this use of まま that we get わがまま, which I’m sure you’ve heard,

which means selfish or selfishness.

Why does it mean that?

Well, 我が/わが means I or we and it can be put next to a noun to denote possession of it. So we can say わが家, which means my house or our house.

わがまま means my unchanged condition, but this clearly is influenced by expressions like 思いのまま or 心のまま.

So this わがまま means my unchanged condition implying my will,

wanting the world to go in accordance with my will,

wanting the world to be 思いのまま, 心のまま.

So as we see the whole of まま, we don’t have to have all these different definitions of it.

We can see that every time we use it it means the same thing.

It means unchanged condition…