Lesson 18: って tte = は wa?? Mysteries explained! Toshite, toiu, to suru, ou to suru, tteiu

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about trying to do something

and from there we’re going to broaden out into the wider meanings of the と quotation particle because this is a very central part of Japanese that’s used all the time.

So we need to get a firm understanding of what it is and how it works.

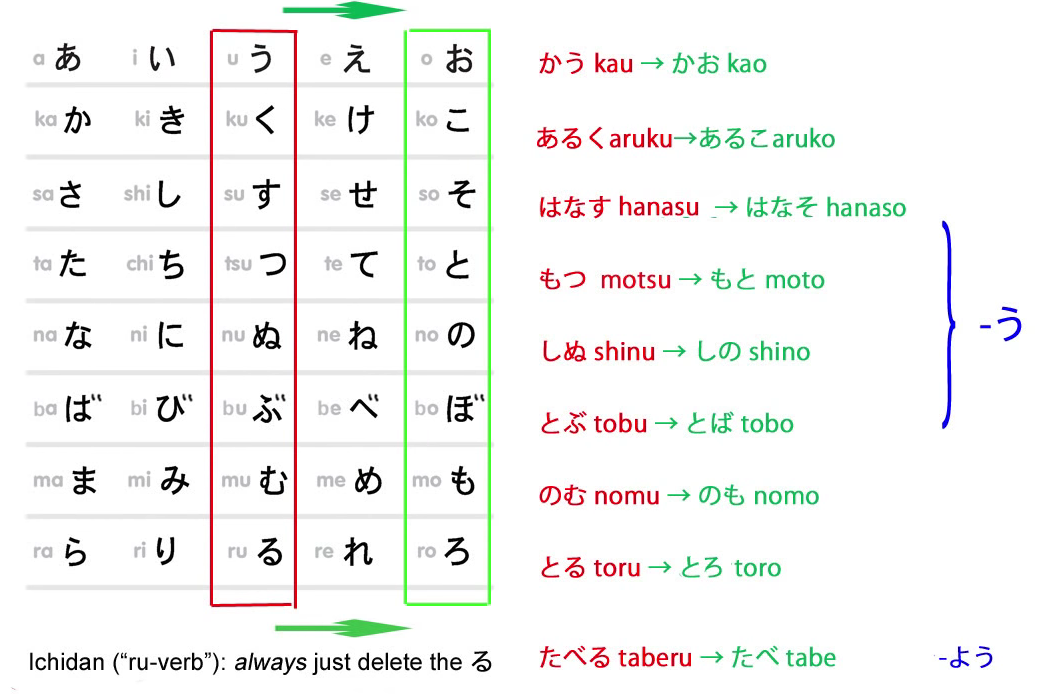

Now, last week (Lesson 17) we learned the volitional helper う and よう which makes a word end with the sound おう or よう and expresses will.

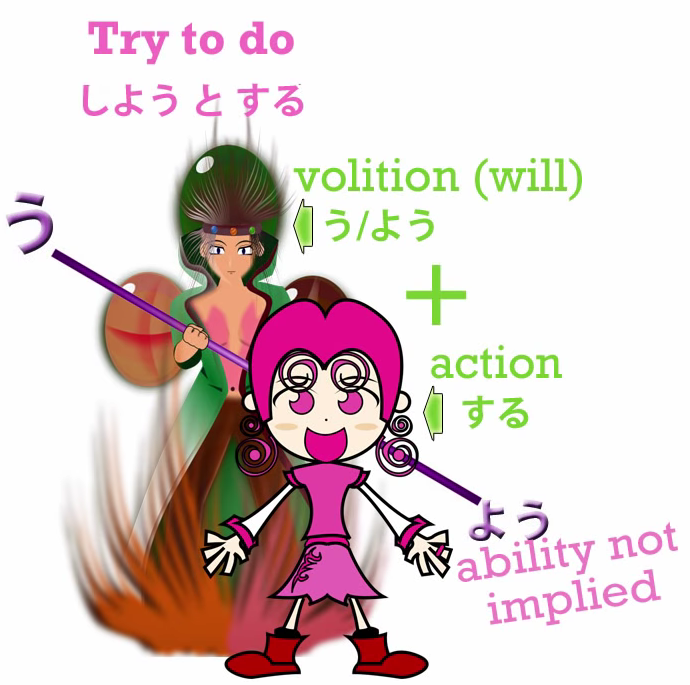

If we’re trying to do something we use the volitional for this.

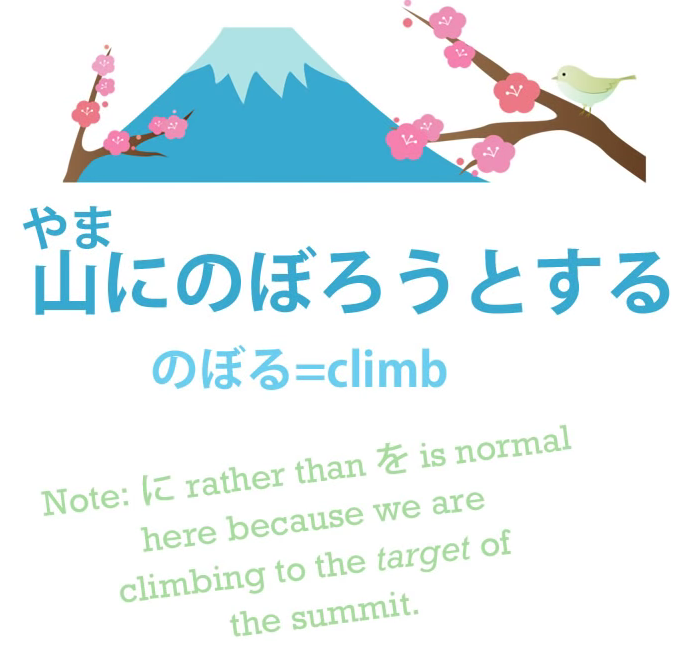

So if we say, 山にのぼろうとする, this means try to climb mountain.

Why does it mean that? What’s this construction actually doing?

Well, のぼろう expresses the will to climb.

If we say 山にのぼろう, we’re saying, Let’s climb the mountain.

Literally, set our will toward climbing the mountain.

おうとする / とする

のぼろうとする means doing the act implied by setting our will to climb the mountain.

If we just wanted to say climb the mountain, we’d just say, 山にのぼる.

But we’re not saying climb the mountain, we’re saying try to climb the mountain.

Therefore, do the action implied in setting our will / enact our will to climb the mountain,

whether we succeed in actually climbing it or not.

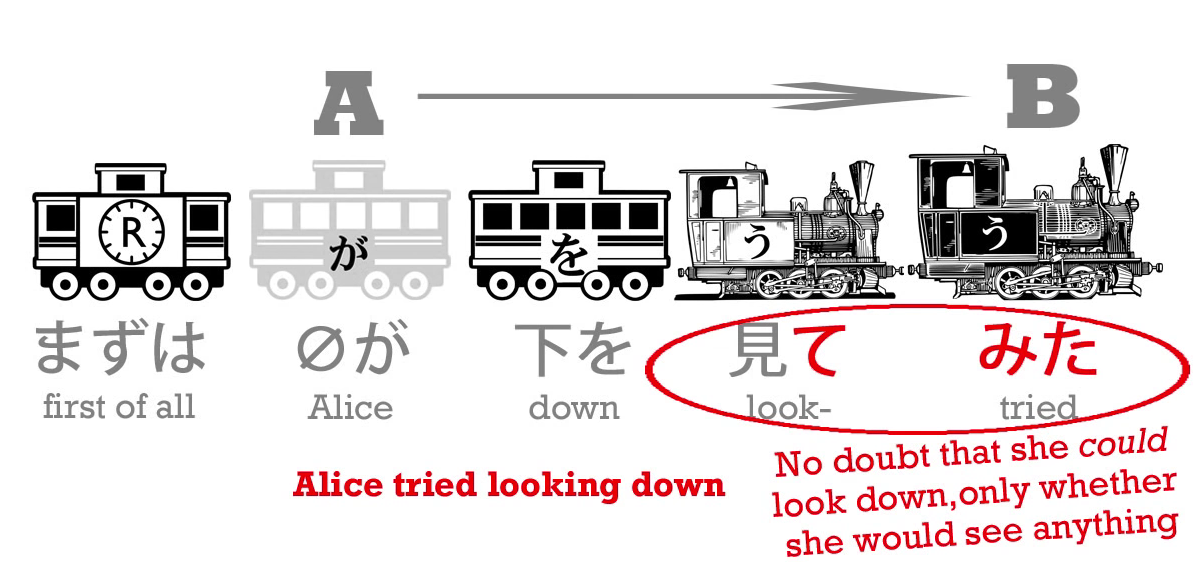

Some people find the distinction between try climbing and try to climb confusing.

And that’s really only because of the way it’s expressed in English.

In Japanese, as we learned recently (Lesson 16), if we want to say,

try climbing the mountain, we say, 山にのぼってみる.

The difference is that try climbing / try eating / try swimming doesn’t imply any doubt

about the fact that we can actually do it.

It implies doubt about what would be the result when we’ve done it.

Try eating - we know we can eat, but don’t know if we’ll like it.

Try eating - 食べてみる - means eat and see.

Eat it and then see what the result is, see if you like it, see if you don’t like it.

山にのぼってみる means climb the mountain and see.

See whether it was hard, see what the view’s like from the top.

ケーキを食べようとする - try to eat the cake - implies that we don’t know whether

you can in fact eat the cake or not, but try it anyway.

Maybe it’s a huge cake and it would be very hard to eat it all.

So してみる - do and see - implies that there’s no doubt about the fact that we can do it, but there is some doubt about what the result of having done it is going to be.

Are we going to like it?

Is the building going to fall down?

We don’t know what will happen when we’ve done it, but we know we can do it.

しようとする implies that we don’t know whether we can do it or not,

but we are going to try to do it.

So, an important thing here is to see what the と-particle is doing.

-と is encapsulating the sentence that came before it:

山にのぼろう - will to climb the mountain.

It isn’t quoting it.

It’s not something we’ve said; it’s not something we’ve thought, exactly.

The point is that it’s taking the essence, the meaning, the import of that 山にのぼろう

and putting it into action.

And we’re going to find that in other cases.

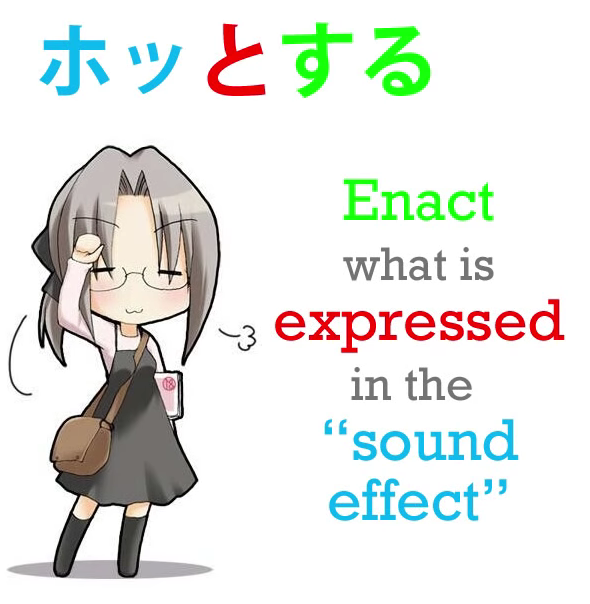

For example, we may read that someone ホッとした . Now, what does that mean?

ホッ is in fact a sound effect.

It’s the sound effect of breathing a sigh of relief: ホッ.

But ホッとする actually does not mean breathe a sigh of relief.

What it means is, feel relief / be relieved.

So what we’re doing here is enacting the idea, the feeling, expressed in ホッ, the sigh of relief.

Just as in 山にのぼろうとする we’re enacting the feeling,

the import of setting our will toward climbing the mountain, that is, trying to climb it.

とする & にする

Now, similarly, if we say さくらを日本人とする, it means regarding Sakura as a Japanese person.

Now, we might also say, さくらを日本人にする, but that means something quite different.

It means turn Sakura into a Japanese person.

に is the target of an action.

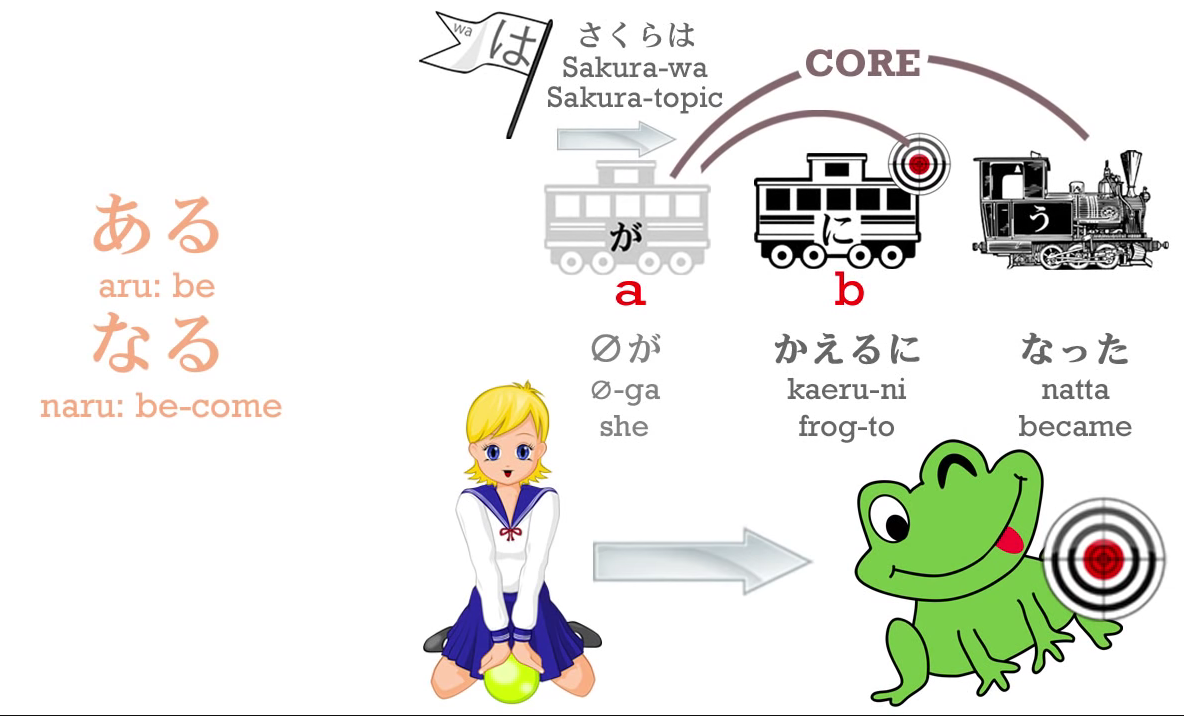

A little while ago we had a lesson (Lesson 8) in which we talked about

さくらがかえるになる - Sakura becomes a frog.

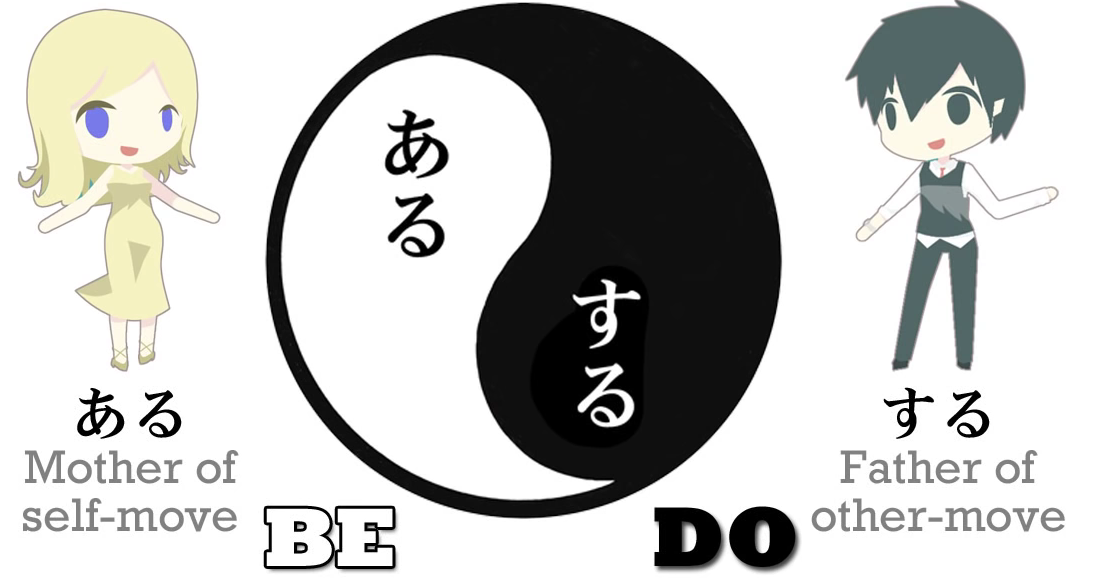

Now, we’ve also talked about (Lesson 15) the way that ある and する are the Eve and Adam of Japanese verbs,

ある being the primary self-move verb and する the primary other-move verb.

なる is very closely related to ある - ある is be, なる is become.

And so if we say になる it means to become something.

If we say にする that’s the other-move version of になる.

It means to turn something into something.

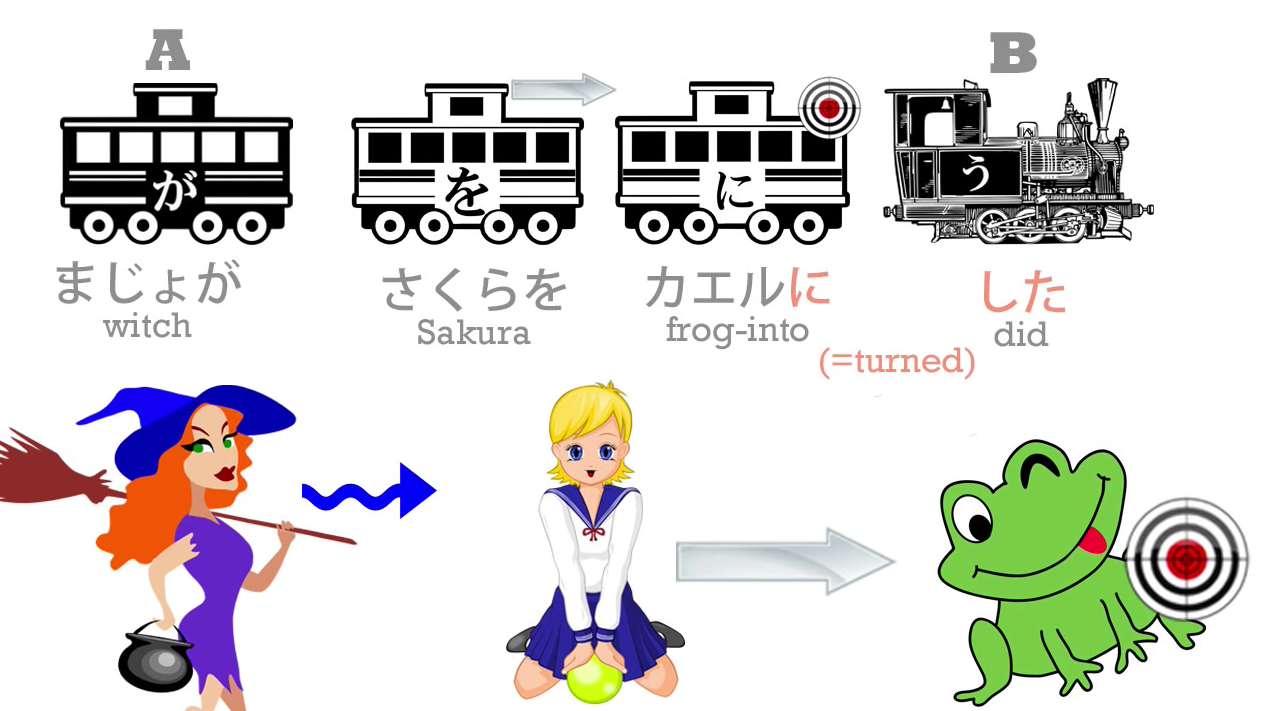

So if we say, まじょがさくらをカエルにした - the witch turned Sakura into a frog.

::: info

カエル is just another way to write frog, via katakana. Animals are usually written that way.

:::

さくらを日本人にする - turning Sakura into a Japanese person;

but さくらを日本人とする - regarding Sakura as a Japanese person / taking Sakura as a Japanese person.

かばんをまくらとする.

かばん is bag, まくら is pillow and this means using your bag as a pillow.

You’re not turning your bag into a pillow, it’s not becoming a pillow,

but you’re regarding it as one and using it as one.

So here we have some of the uses of -とする.

Generally speaking, it relates to how we regard something.

として

Now, if we say -として, this isn’t so much the act of regarding something as something,

but seeing something in the light of being something.

So, in English it would usually be translated simply as as or for. Or being in the role of

So, こじん/個人としての いけん/意見 means my opinion as a private person, as opposed to, say, my opinion as president of the Frog Jockey Society. - just another example sentence (contrast in words private person & president), not some difference in the function of として. The wording may delude to Dolly meaning it as if it was として that had an opposing role there.

Or we could say, アメリカ人として小さい - “She’s small for an American / As an American, she’s small.

So we can see that the quotation function of -と is used not only to quote ideas and thoughts, but also to take the feeling of something and bundle it up and then say something about it.

::: info just in case, this comment may help some in regards to とする & として.

:::

:::

という / と言う

Of course, the most basic thing that can follow -と is いう,

in which case it’s a literal quotation,

-という/と言う (it’s usually pronounced not so much -という but as -とゆ).

And this again can be used not just in a literal quotation but also saying

how something is said or what it’s called.

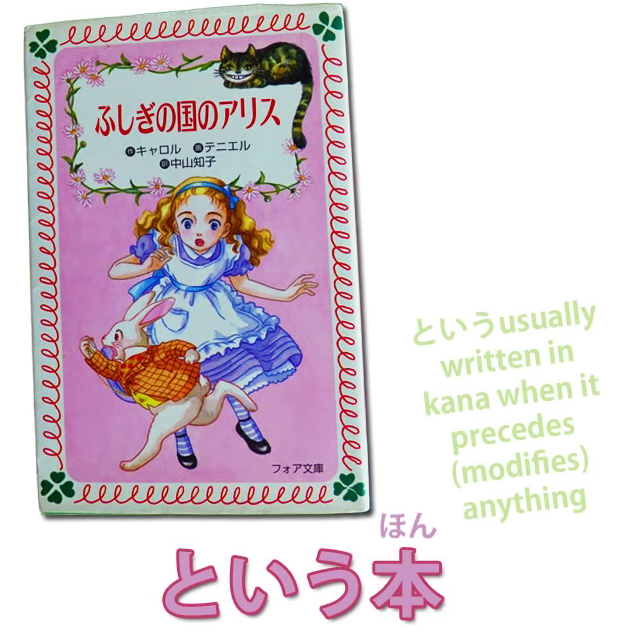

So, ふしぎの国のアリスという本, means book called ふしぎの国のアリス

っていう / って言う

And the -と in -という can be reduced simply to -って.

So we can say -っていう - ふしぎの国のアリスっていう本,

or it can be reduced down to just -って.

ふしぎの国のアリスって本 still means The book called Alice in Wonderland.

So people sometimes get a little confused when they just see this -って.

It means -と or -という, but the thing that really confuses people sometimes is that

it can also be used in place of the は-particle.

って used in place of は

Now, this seems particularly strange, until you realize what it’s actually doing.

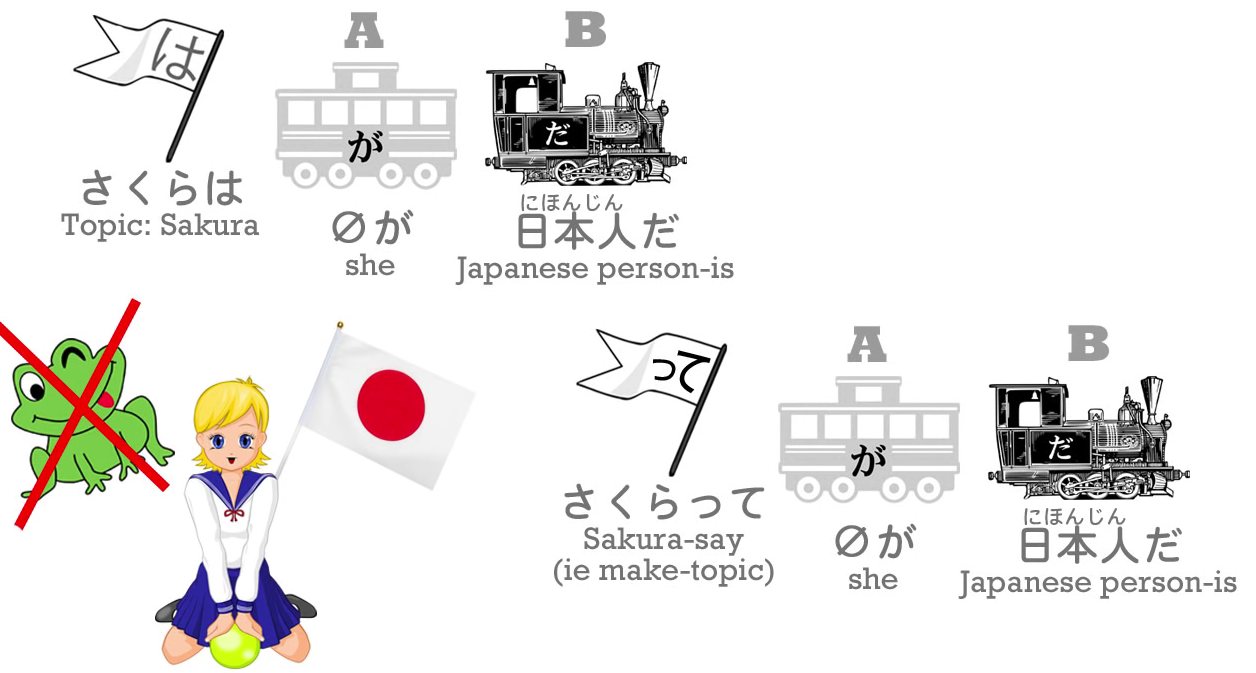

If we remember what the は-particle is, the は-particle is the topic-marking particle.

So when we say さくらは (zero が) 日本人だ, we can put that into English as

Speaking of Sakura, (she) is Japanese person.

Now, does that start to make things a little clearer?

さくらって(zero が)日本人だ - Sakura -say, (she) Japanese-person is -

Sakura -speaking of, (she) Japanese-person is - Sakura (topic), (she) Japanese-person is.

Now, we can’t say -と or -という in place of the は-particle.

It’s a very casual use.

We just use -って.

But you can see that it’s really, even though it’s very colloquial,

it’s not just some random and inexplicable thing.

It’s setting up Sakura as the thing we’re talking about, just as は is.

Now, there are other extended uses of -と.

We’ll cover those as we come to them.