くらい (kurai) VS ほど (hodo) What they mean and why they mean it.

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about

two words that often cause people difficulty and confusion in immersion

because they’re often not explained very clearly,

so it’s difficult sometimes to understand what exactly it is that they’re doing.

The two words are くらい and ほど.

Now, I’ve had a lot of requests for くらい, here and on my Patreon,

and quite a few requests for ほど.

And I’m going to deal with them together

because I think they can throw a little light on each other.

And before we begin, I’ll just say that if you have any words that are causing you trouble,

bringing you to a halt in understanding things in your immersion,

please put them in the Comments below and I’ll either reply right away

or add them to my list of things to deal with.

Right, so, ほど and くらい.

They’re both nouns, of course.

Practically everything in Japanese that isn’t a verb or an adjective,

as we know, is in practice a noun or a noun-like entity.

So, what is a ほど? What is a くらい?

Both of them represent an extent or an amount of… anything: time, money, distance, etc.

However, the main difference between them is that

ほど tends to imply that the amount or degree involved is great,

and くらい either marks it as indefinite, as something we’re not sure about,

or in some cases which we’ll talk about a bit later, that it is small,

that it’s less than we might have expected or hoped.

So, to illustrate this difference, let’s look at them both in a very simple construction.

**これくらい means: about this much, about this amount, about this far, about this fast,

**about this temperature, whatever.

これほど means: this much, this amount, this hot, this cold,

but it’s stressing that this is a large extent, a large degree.

ほど

So, if we say これほど悪いとは思わなかった,

we’re saying, I didn’t think it was this bad.

So, the これ (this) modifying ほど is not only saying this bad,

it’s saying that this bad is a lot, this is more than we might have expected or desired.

Negatively, if we say それほど悪くない, we’re saying it’s not that bad.

Now, what’s それ referring to in a case like this?

It can be referring to something we’ve already referred to,

to a degree or an extent that we’ve already been discussing,

but also, just as in English, それ (or that) can simply mean

an amount that we might have expected.

So, again, the thing modifying ほど, the それ,

represents a great amount, an upper limit,

and then we’re falling short of that upper limit marked by ほど.

So, それほど悪くない means not that bad —

either not that bad as we have been discussing or as is implied in the conversation,

or simply not that bad, which works exactly the same as it does in English —

the that when there’s no reference point simply means

what we might have expected or what it might have been.

So if we say in English it’s not that bad, we mean

it’s not very bad, it’s not as bad as it might have been.

And the same with それほど悪くない.

If we’re not referring to a specific, defined that, then we’re saying

it’s not very bad / it’s not all that bad.

And again, ほど is often used to mark one side of a comparison,

and once again ほど represents the greater side, the upper limit.

So if we say 私は彼女ほど若くない we’re saying I’m not as young as she is,

I’m not young to the extent that she is, and her extent is the higher extent

and therefore it’s the one modifying ほど.

ほど as a noun

Now, ほど can be used as an almost independent noun

representing the upper limit of something.

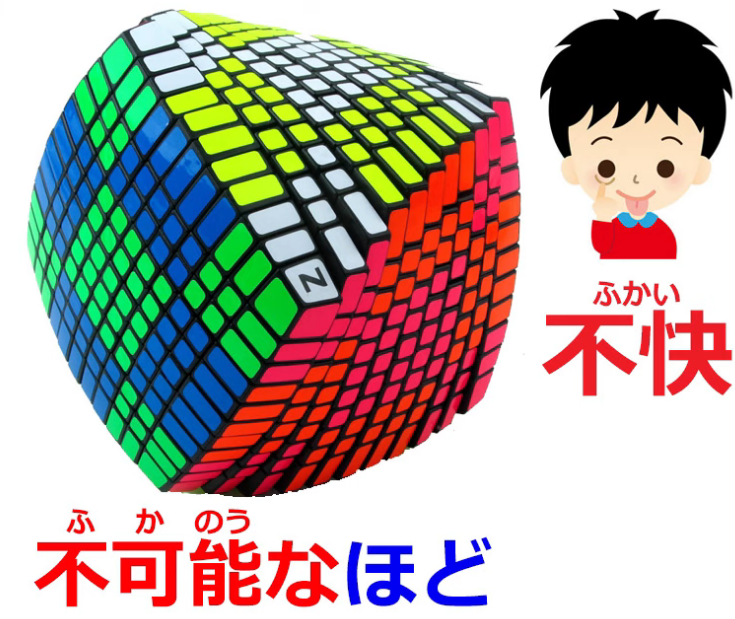

So if we say 不可能なほど, we’re saying

(不可能: 可能 means possible; 不可能 means impossible)

不可能なほど means the upper limit of impossibility.

This is not just 不可能, not just impossible, it’s the ほど of 不可能,

it’s the upper limit of 不可能, it’s the height of impossibility.

Or 不快なほど失礼 — 不快 is unpleasant, dislikeable; 失礼, of course, is rudeness.

This is rudeness to the upper limit of unpleasantness / dislikeableness.

And these ほどs where we use an adjectival noun and add なほど —

the upper limit of that adjectival noun,

using that adjectival noun to modify the ほど —

very often they tend to be negative things but they can be more neutral,

for example, we might say 不思議なほど

— the upper limit of mysteriousness, absolutely mysterious.

::: info

This phrase above is apparently an expression that can also mean wondrous/marvellous

:::

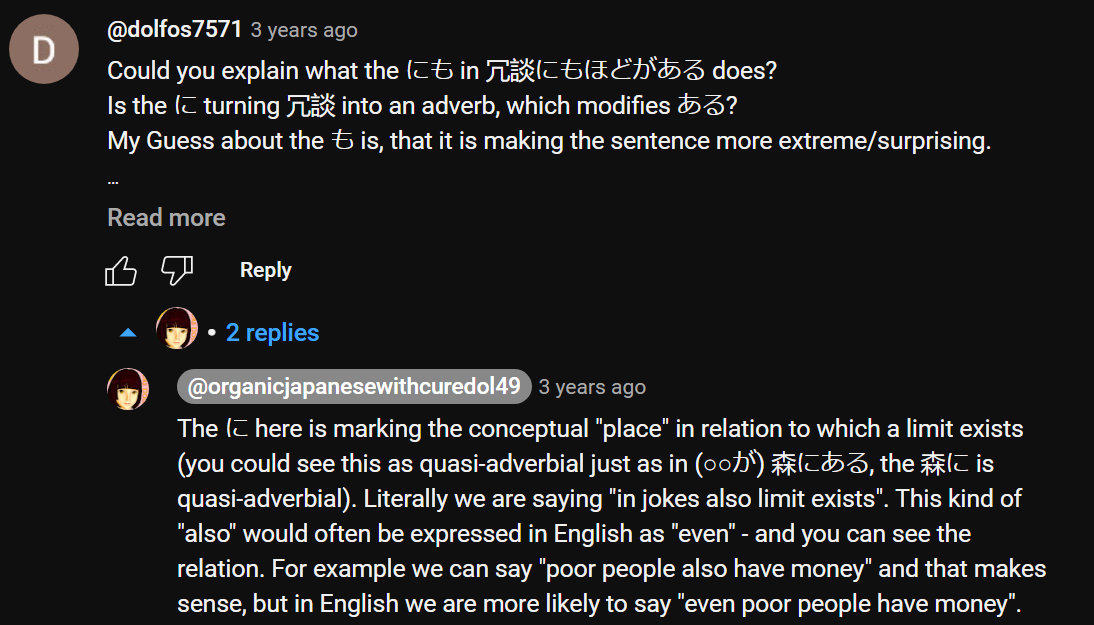

And another commonly used expression with ほど is ほどがある,

and this really means an upper limit exists.

And this is usually used in complaining about something.

So we say 冗談にもほどがある, which is literally saying even a joke has an upper limit,

and what that usually means is, what you’re saying / what you’re doing goes beyond a joke.

Jokes have an upper limit and you’ve passed it.

バカにもほどがある (stupidity has an upper limit),

which is a bit like saying, Even you can’t be that stupid

or you’ve passed the upper limit of stupidity.

ほど for forming comparisons

And perhaps the commonest use of ほど,

the one that you’ll probably see all the time,

is its use in forming comparisons.

Now, there are various kinds of comparison in Japanese,

but ほど is used particularly when

we’re stressing the extreme quality of something.

It’s often used for comparisons that are essentially exaggerations

but making the point that something is very much whatever it is we’re saying it is.

So, we might say, 死ぬほど暑い (it’s hot to the extent of dying);

肌を刺すほど寒い (it’s cold to the extent of penetrating the skin);

信じられないほど美しい景色

(scenery that’s beautiful to the extent of being unbelievable).

And this ほど which is used for exaggeration, for literary purposes,

just for making a point very strongly,

is probably the ほど that you’re going to see more of the time than any other.

It’s a very common use of ほど.

くらい

So, let’s look at くらい.

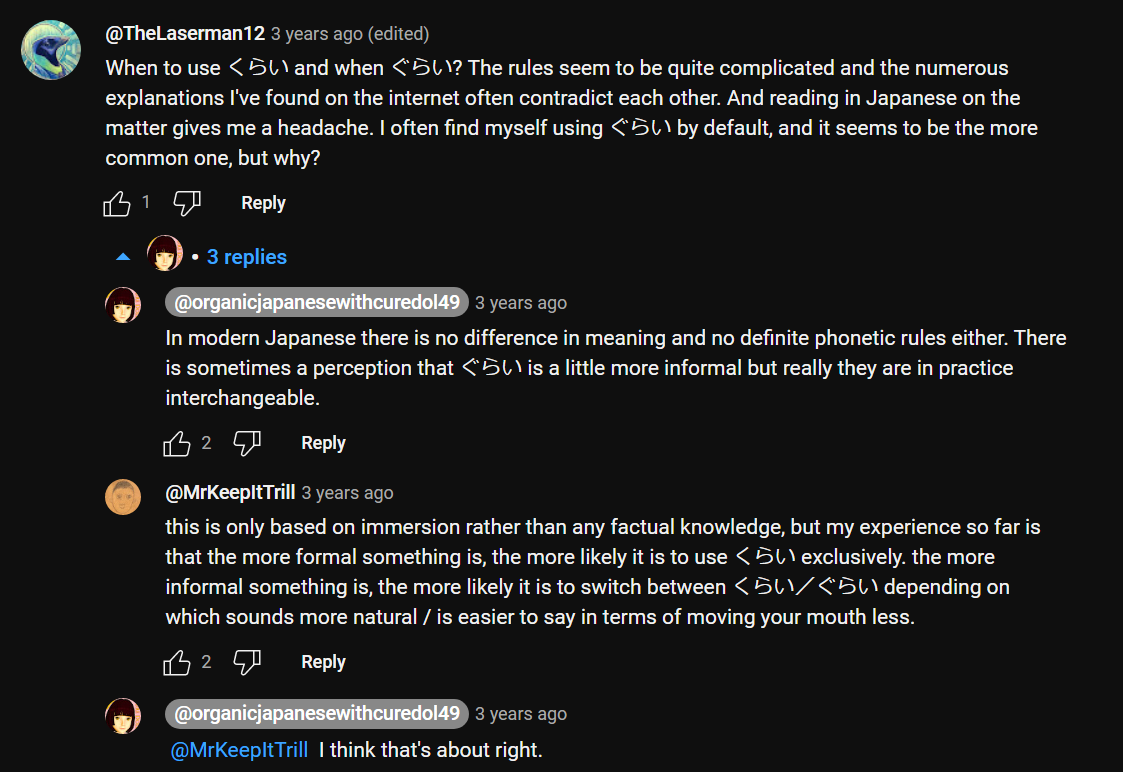

くらい is most commonly used for approximation.

So we might say, 到着するのは八時ぐらいです —

we’re saying we’re arriving at approximately eight o’clock.

八百円ぐらいです (it’s around eight hundred yen).

And this is very straightforward.

::: info くらい as you can see can sometimes change in sound to ぐらい in some phrases. ::: As to when, that is apparently no longer as clear, as can be read here. But wouldn’t worry much.

We use it whenever we want to talk about an amount, a degree, an extent, and make it vague,

make it clear that we’re not talking about an exact amount or an exact degree.

And the only thing to bear in mind here is that sometimes

Japanese people will use this when in fact the thing in question is exact.

So, for example, we might say, どのくらい掛かりますか? (about how much will it cost?)

And we may be asking for an estimate, if it’s the sort of thing where you ask for an estimate,

but we may also be asking the price in a case where

we can expect the seller to know the exact price,

but somehow it seems a bit less pressing to ask

for an approximate price rather than the exact one.

And people will also sometimes do this

when they’re talking about a time of arrival or… anything.

And this is partly because Japanese people are on the whole very precise,

so if they think there might be any chance of the time being slightly different

or any fact being slightly different from what they’re saying,

it feels a bit safer to vague it up a little bit

so that you haven’t committed yourself to something exact

that might not turn out to be exactly true.

くらい as a small extent of something = at least

Now, the other use of くらい (or ぐらい), as I mentioned before,

talks about an extent and makes the point that

the extent is what we consider to be a small one

rather than the large one that ほど implies.

So, if we say 今日くらい家族と過ごそう,

we’re saying Today, at least, let’s spend as a family.

And it’s that くらい which gives us the at least meaning.

It shows that when we are saying today we’re not just saying today,

we’re implying that maybe we don’t spend much time as a family,

maybe we won’t be able to spend time as a family again,

but today at least let’s spend time as a family.

くらい as complaining about something

And very often this くらい is used when one is complaining about something

and when one is really saying that not only is the くらい small,

but even that small くらい wasn’t forthcoming.

And when it’s used like that it’s often accompanied by another at least expression

like 少なくとも or せめて,

and often marked at the end by a marker of regret such as のに.

So, we might say, 少なくとも「ありがとう」ぐらい言ってくれてもいいのに,

which literally is at least as little as thank you if you kindly said would be good but…

In natural English, we’d probably say You might at least say thank you.

What we’re here saying is that as little as thank you, if you had kindly said, would be good,

and we’re adding のに, which, as I’ve explained elsewhere,

is in fact a contrastive clause connector.

It’s used to connect one logical clause to another to make a complete sentence

with the implication of but,

that the second clause somewhat contrasts or contradicts with the first,

but it’s often used like this as a sentence ender.

And the implication here is,

it would be good if you said as little as thank you, but (you don’t even do that).

So, I hope this clarifies くらい and ほど.