Lesson 38: Know when it isn’t means it is: mysteries of じゃない janai, ではない de wa nai

こんにちは。

Today we’re going to talk about something that puzzles many learners of Japanese, especially

once they’ve learned a little Japanese and they start reading Japanese or listening to anime etc.

And this is the fact that Japanese people often make what appear to be negative statements when they may mean in fact a positive statement.

For example, someone may say さくらじゃない, which would appear to mean That isn’t Sakura.

But its actual meaning is That is Sakura, isn’t it? or even simply That is Sakura.

Now, how does this work, how do we recognize it, and how do we understand it?

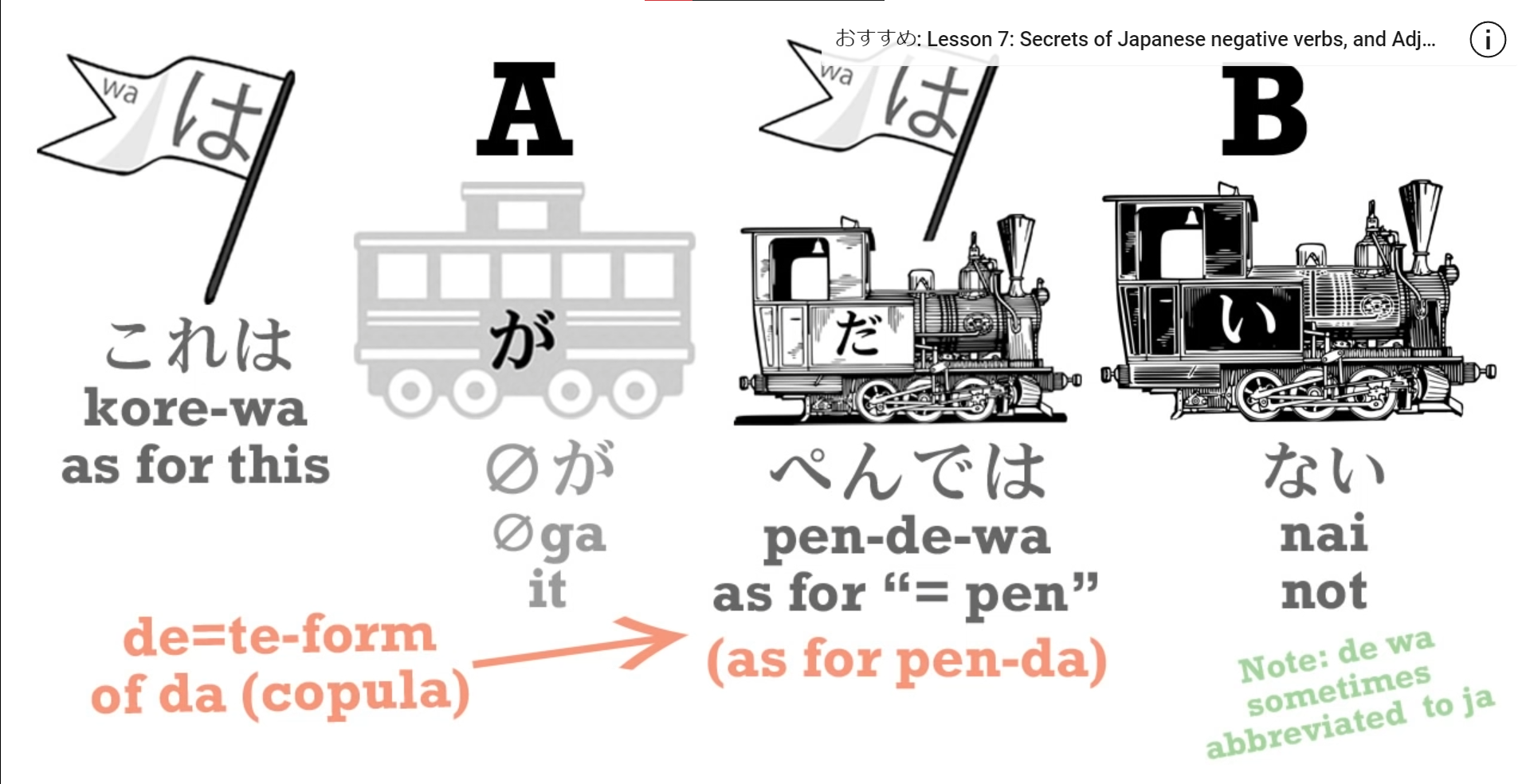

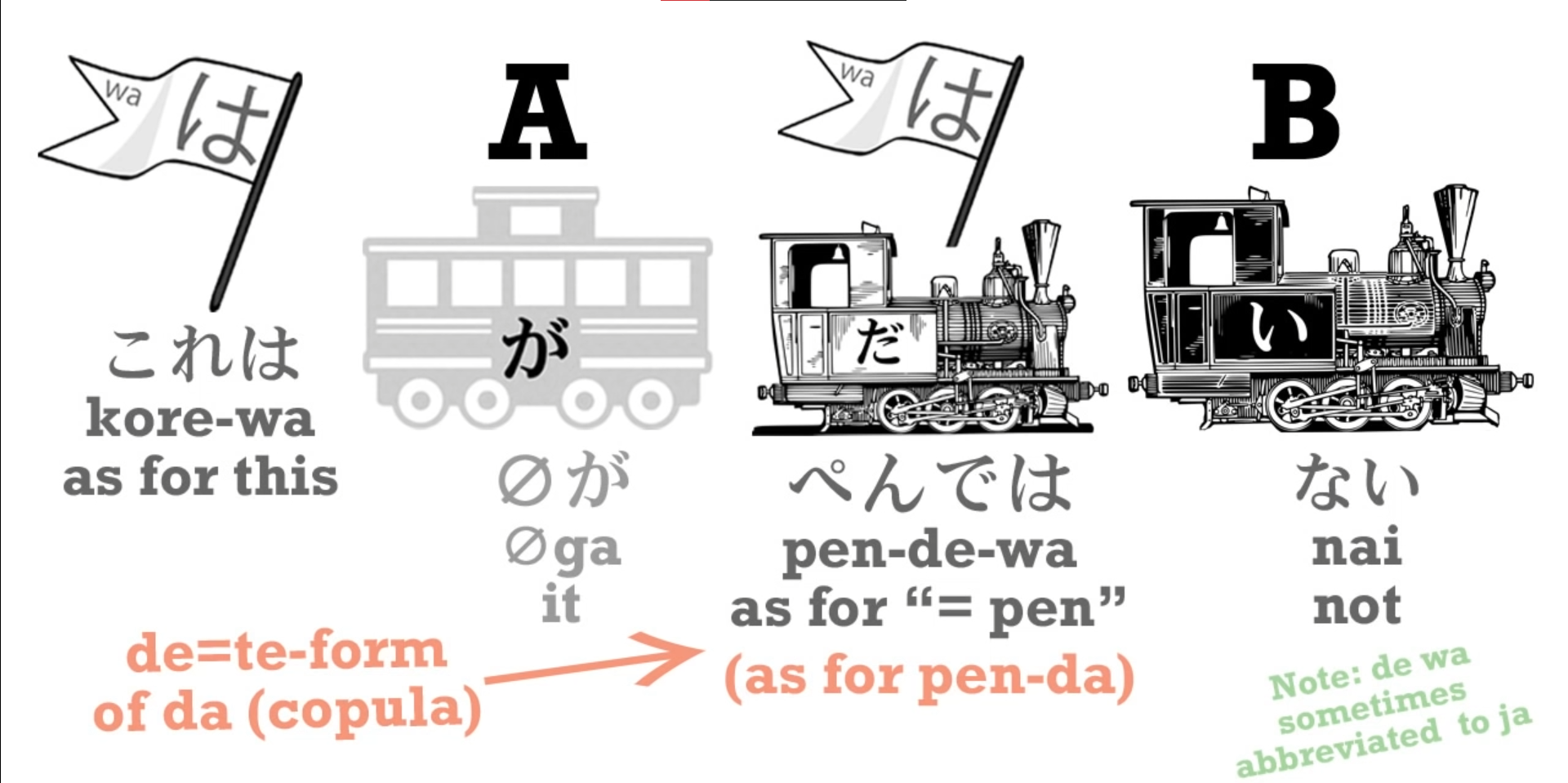

For a start, じゃない is the contraction of ではない which, of course, is the negative of the copula, as we learned right back in our lesson on Japanese negatives.

So, A,B だ or A,B です means A is B.

A,B ではない (or ではありません) means A is not B.

So there is no question here that we are in fact hearing what is, grammatically, a negative statement.

So how do we interpret this?

Well, to begin with, let’s remind ourselves of the fact that negative questions are used

in most languages, including English, to elicit a positive response.

So if we say It’s a nice day, isn’t it? we mean that it is a nice day and we expect our hearer to agree.

If we say Are you Sakura? this is a neutral question.

We’re not suggesting that we either think it is or it isn’t.

We’re simply asking the question.

But if we say Aren’t you Sakura? then we are in fact indicating that we think you are Sakura.

And a negative question asking for a positive response like It’s a nice day, isn’t it?

is common certainly to all the languages I know.

In French we have n’est-ce pas, in German we have nicht wahr, and of course in Japanese

we have ね, which is originally a negative question.

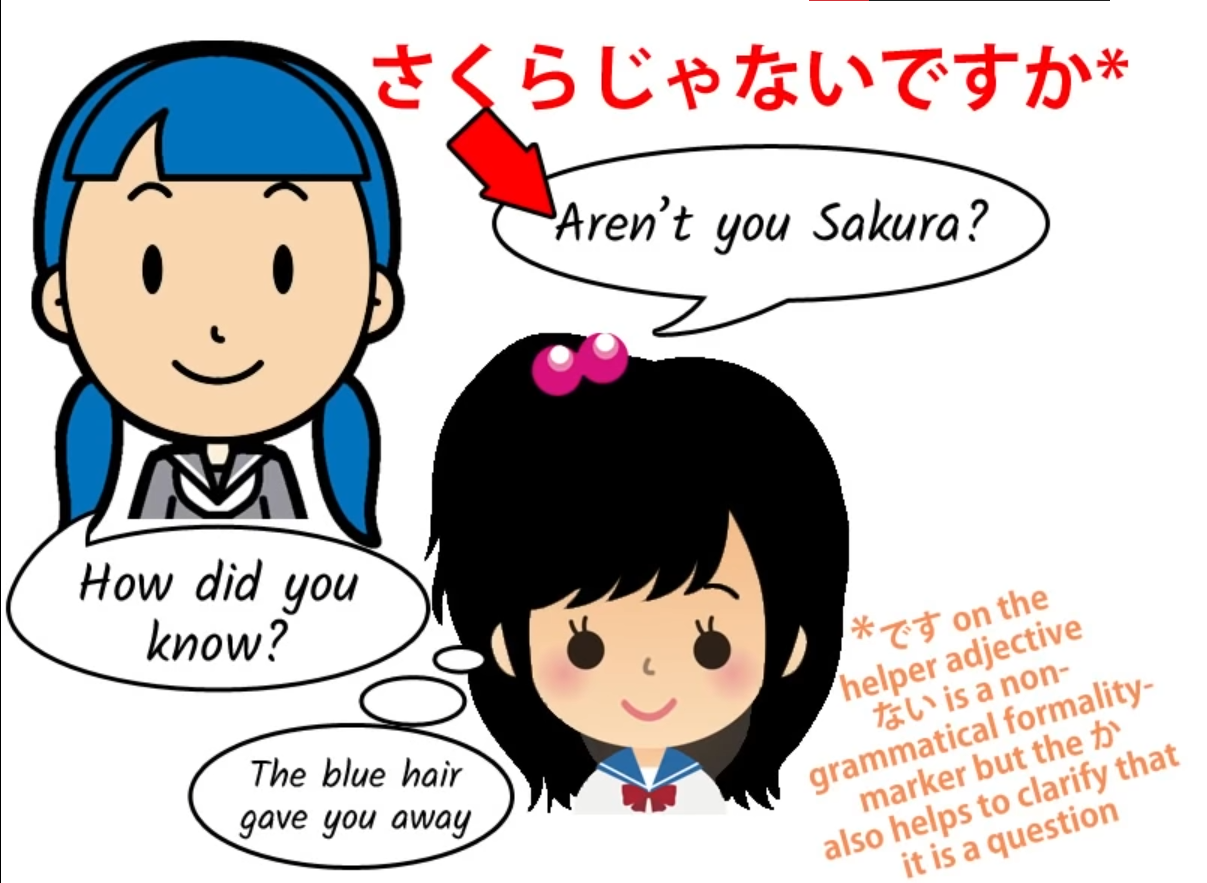

So if we say さくらじゃないですか we’re saying exactly the same thing as in English

Isn’t that Sakura? meaning we think it is.

The first problem that arises here is that, while we say in formal speech さくらじゃないですか because in formal speech the か acts as a verbal question mark, turning any statement into a question, we don’t usually use か as a question-making sentence-ender in ordinary, non-formal Japanese.

So what would be さくらじゃないですか in formal Japanese becomes さくらじゃない in regular Japanese.

さくらじゃない has fundamentally three potential meanings. (indicated by tone in speech)

We can say さくらじゃない。 — that means That isn’t Sakura.

We can say さくらじゃない? and that means That’s Sakura, isn’t it?

But we can also say, perhaps meeting Sakura after quite a long time, さくらじゃない!,

and that certainly doesn’t mean it isn’t Sakura and it’s not a question either.

We’ve actually recognized her and what we’re saying is something that could perhaps

best be rendered into English as If it isn’t Sakura! meaning it is Sakura.

Now there’s nothing particularly mystical and Japanese about this.

We do the same sort of thing in English.

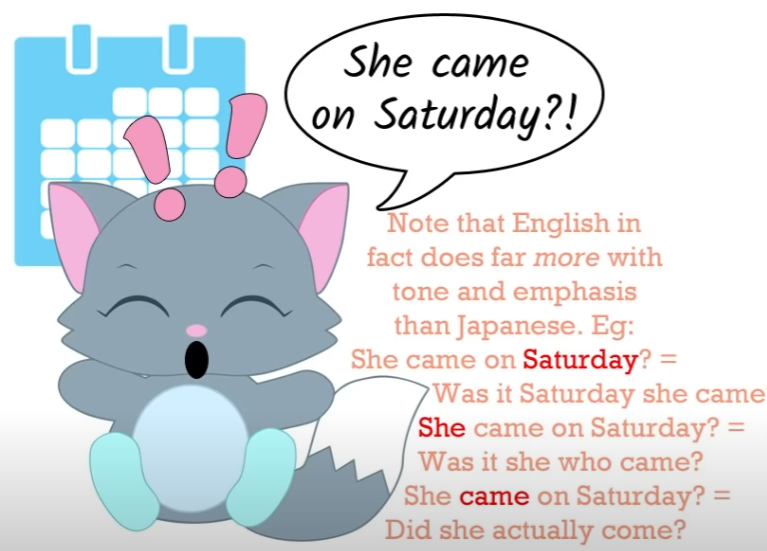

For example, if we said She came on Saturday, that’s simply conveying a piece of information.

If we say She came on Saturday? we’re asking whether she came on Saturday or not.

And if we say She came on Saturday?! we’ve just received the information that

she came on Saturday and we are expressing surprise about it.

We know how to interpret this in English and it’s easy to learn how to interpret じゃない

in Japanese once we understand the range of meaning it possesses.

じゃない gets used with other meanings too.

Particularly, it gets used as a negative question tag-ending very much like ね.

For example, we might say 暑いじゃない

which means pretty much the same thing as 暑いね.

It’s something like a tag-question, expecting our listener to agree with us.

And we can note here that there’s no ambiguity at all in this, because 暑いじゃない is not the negative of 暑い – that’s 暑くない.

And it can also be put after verbs.

For example, もう言ったじゃない, which means I already said that, didn’t I?

We should also note that じゃない is often reduced to just じゃん in very colloquial speech, and it’s often used in that way when it’s affirming something or asking for confirmation.

Now, it’s clear that these expressions are very colloquial and in fact so colloquial

that when we use them with a verb or an adjective they’re not in fact grammatical.

And the reason for this, as I’ve already alluded to, is that, for example,

暑いじゃない is not the negative of 暑い because that’s 暑くない.

Why can’t we use じゃない with verbs or adjectives?

Well, that’s because, as we learned right back in the first lesson,

じゃない is in fact ではない, which is the negative of the copula.

So if we say これはペンだ we’re saying This is a pen; if we say これはペンではない,

we’re saying This is not a pen, and you can’t properly use ではない with anything but two nouns.

I don’t actually think that these colloquial statements are fundamentally ungrammatical.

It’s just that being colloquial may leave a few steps out of the process.

There are in fact much more formal ways of using ではない as a positive statement,

but these of course tidy up the grammar.

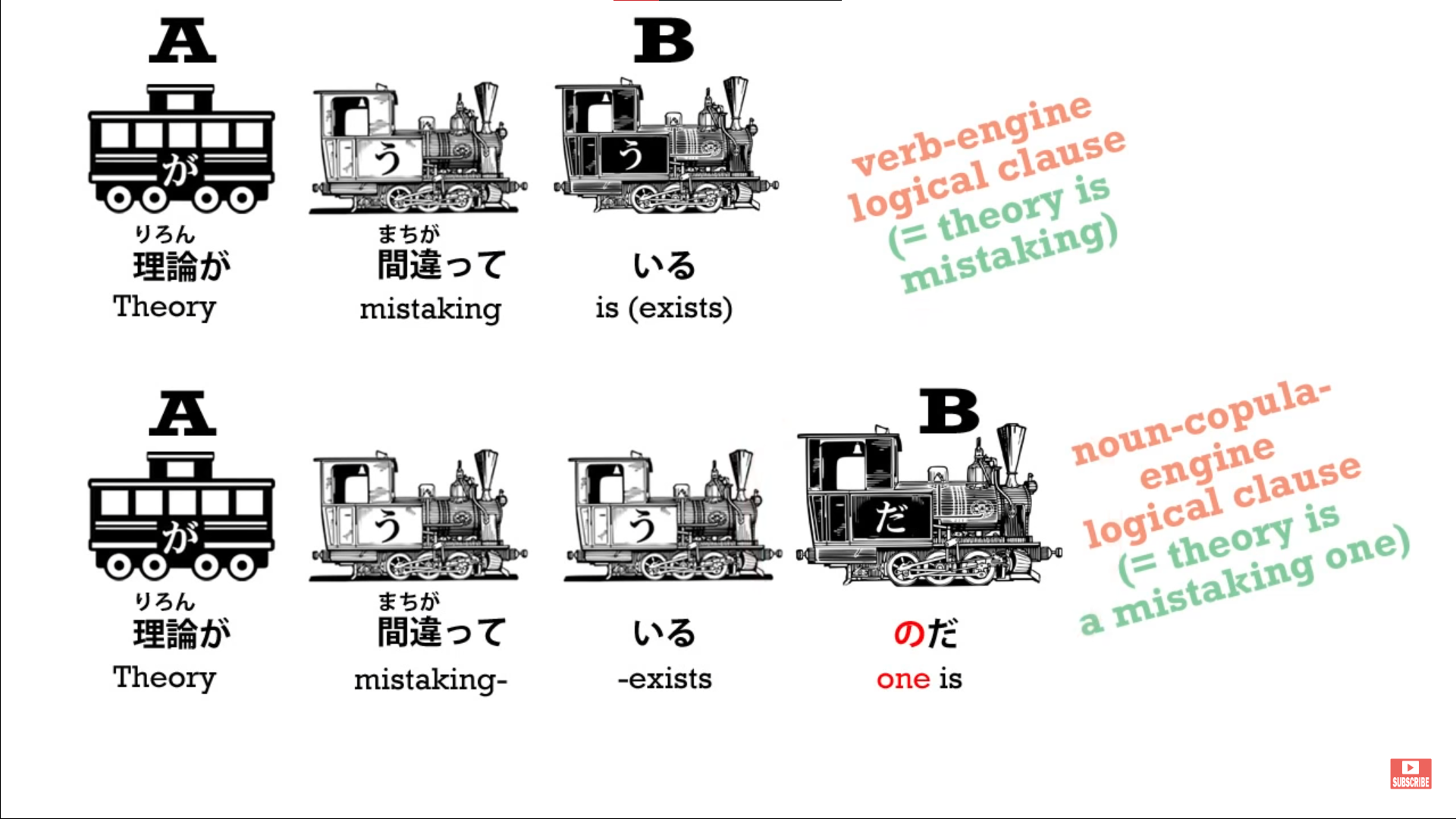

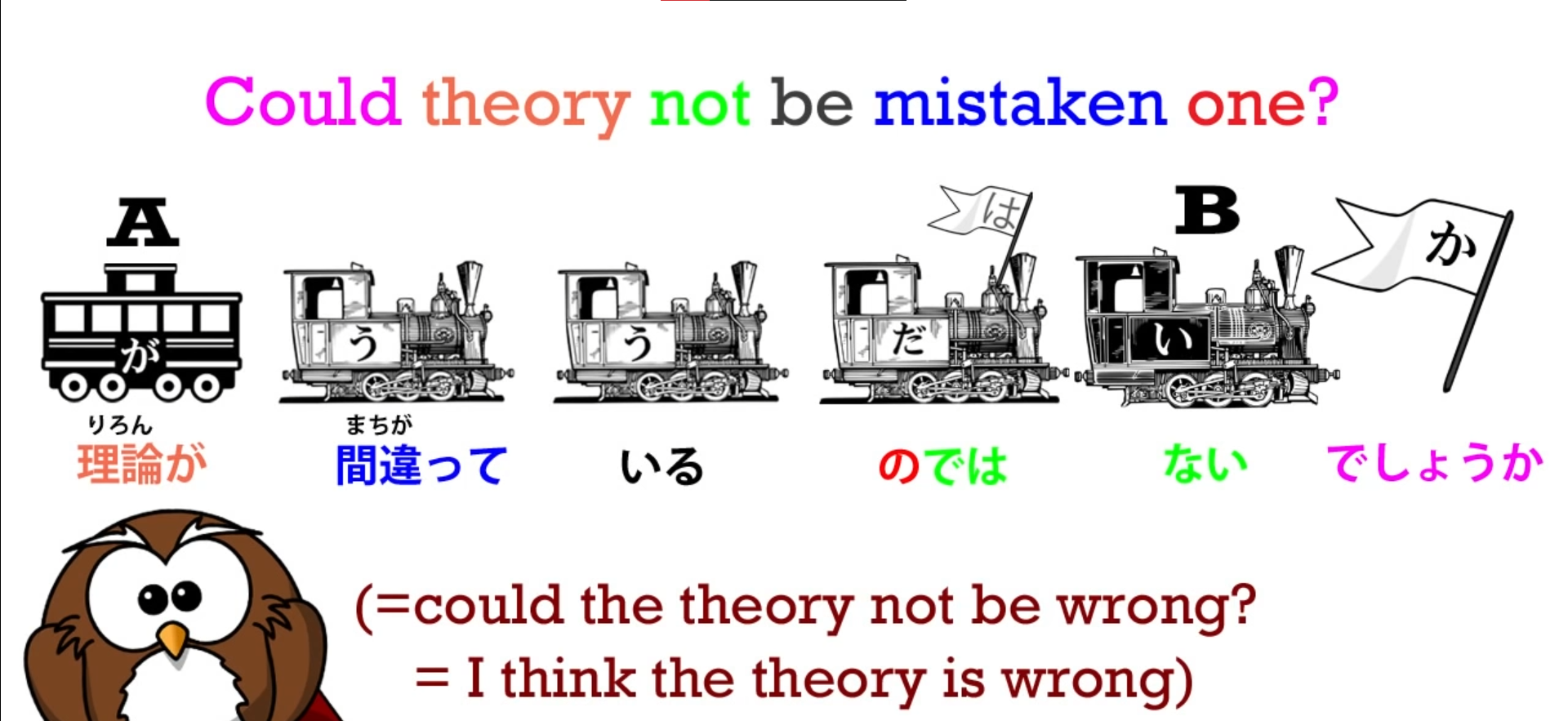

So, for example, if we say その理論が間違っているのではないでしょうか,

we’re saying Might that theory not be in error?

And we see we have essentially the same construction that we’ve been dealing with before:

その理論が間違っている… ではない, but that の turns it into a grammatical statement.

Why?

Because その理論が間違っている means literally that theory exists in a state of mistaking. That’s a verbal clause complete in itself.

However, when we add の, that の, as we’ve seen in other lessons, plays the role

of a pronoun like thing or one which is being modified by 間違っている.

So now we have that theory exists in a state of error one.

So we have two nouns and we now need the copula to join them together.

So その理論が間違っているのではない means that theory existing-in-error-one is not.

The でしょうか doesn’t add anything grammatically to the statement.

As we know, adjectives like ない stand on their own.

They don’t require a だ, even though they get a です as a mere decoration, a non-grammatical decoration, in formal speech, so what でしょうか is doing here is it’s simply a flag put at the end of the complete grammatical statement:

その理論が間違っているのではない.

でしょうか turns it explicitly into a question and into a suggestion rather than a statement.

So we’re saying Might that theory not be a mistaken one?

Now, this can mean what it seems to say.

It can mean that we’re in some doubt and we’re actually asking whether that might not be the case.

But a lot of the time this is used not just as an assertion but as a quite strong assertion.

We might use this to sum up our argument when we have definitively disproved the theory in question.

An American writer or speaker might sum up such an argument with “It is now clear

to anyone with an intelligence greater than that of a Roomba that this theory holds about as much water as a topless thimble in the Sahara Desert.”

However, that kind of definite assertion in Japanese is not considered either polite or very persuasive.

It sounds as if you’re trying to make up for a weak argument by a strong assertion.

So the equivalent Japanese speaker may sum up the same completely persuasive argument

with ですからその理論は間違っているのではないでしょうか.

And that means exactly the same thing, allowing for cultural differences…

::: info

if anything is still unclear, delving into the comments of the video might be helpful.

:::