Japanese Structure INVERTED: the strange life of しか. How it really works. Lesson 87

こんにちは。

Today, I’m afraid I don’t have any reindeer for you,

but I do have a few deer.

We’re going to talk about the word シカ / 鹿,

which, as you probably know, means deer,

::: info

Just in case, this しか is different to the particle しか of this lesson, hence the Katakana, there is a lot of different しか nouns and whatnot with their own Kanji, but only one particle しか

:::

but there’s another しか element in Japanese which is a particle

and which has a rather unusual effect on the structure of sentences.

So we’re going to look into that effect.

One of my commenters reminded me of a rather charming Japanese word play:

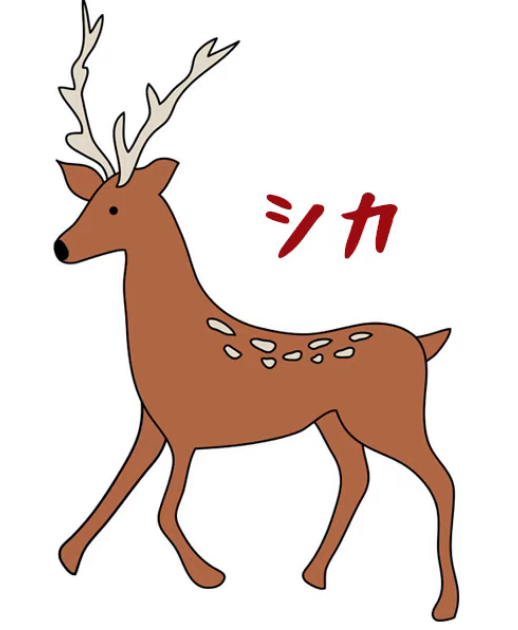

ならならしかしかしかられない, / 奈良なら鹿しか叱られない (how it might be in Kanji form)

and in natural English we would translate this as

In Nara, only the deer get scolded.

It’s useful to know here that

Nara in the Kansai region is famous for its deer.

People go to Nara to see the deer

(and for other things — it’s a lovely historical city).

Strictly, 奈良なら doesn’t mean in Nara.

It means if it’s Nara or, more naturally, in the case of Nara.

But what does the rest of the structure mean?

This is what my commenter was really asking.

The question was, “What is the A-car of this sentence?

Does it have a zero-A-car somewhere, or does it even have an A-car at all?”

What is the A-car of a sentence like this?

Now, the problem is partly that しか has

an unusual effect on the sentence structure,

but it’s also that the receptive helper is used here

which makes it look a bit more complicated than it is.

しか

So let’s start off with a very simple しか sentence.

さくらしかいない。

In natural English we’d translate this as,

There’s nobody here but Sakura.

So what’s しか doing here?

しか does two things in a sentence like this.

It knocks out the が-particle just like か,

so this isn’t something that we’re not already familiar with.

When you have か in a sentence where there would also be a が,

we never say がか or かが.

か displaces が, but the が is still logically there.

That’s what しか also does.

But the other thing しか does is a little bit more unusual.

I don’t know if you’ve ever used Photoshop,

but in Photoshop you can invert a selection.

What happens is that you select an object,

you press the key selection to invert that selection

and what happens is that everything outside of that object is selected.

The object is the only thing there now that isn’t selected.

This is exactly what しか does.

While が, you might say, selects an object, a noun,

and marks it as the A-car, the subject of the sentence,

しか selects that noun, inverts the selection

and marks that as the A-car of the sentence.

So everything other than that selected noun

is now the A-car of the sentence.

So, さくらしかいない literally means

Everyone other than Sakura is not here.

In the deer sentence, which looks a little more complicated,

it’s exactly the same thing: 奈良なら鹿しか叱られない

(if it’s Nara, everything other than the deer are not scolded).

So again, we’re selecting the deer,

inverting the selection to everything other than the deer,

and then that becomes the A-car of the sentence, which is not scolded.

Now, there’s also an implicit relevance clause in this,

so when we say さくらしかいない

we don’t mean there’s nothing here but Sakura: no trees, no bushes, no flying saucers.

We mean there’s nobody here but Sakura.

Now, the いない partly tells us that, but it isn’t just that,

because it also doesn’t mean that there are no bunny rabbits here,

there are no birds, there are no capybara (did I pronounce that right?)

::: info

It should simply select the relevance that no other Sakura / no other people are there.* ---

:::

So しか inverts the selection, but it’s also

what you might call a smart invert: it selects for relevance.

しか in sentences with が-marked subject

However, in some しか sentences there is actually

a が-marked subject, so what’s going on here?

Let’s take a look at one. Suppose we say,

タオルが一枚しかありません.

Again, in natural English: There’s only one towel here.

::: info

Notice how in Japanese they use ありません after しか here.

:::

The が-marked subject is towel or towels.

In Japanese, of course, there’s no distinction between those two things.

And as I explained in my lesson on counters (Lesson 71),

a counter in this kind of sentence is working as an adverb.

It’s telling us more about the engine of the sentence, the verb.

So if we say 泥棒が三人いる,

we’re saying robbers*(=subject)* exist three-person-ly.

If we say タオルが一枚ある,

we’re saying towel*(=subject)* one-flat-thing-ly exists.

If we say タオルが二枚ある,

we’re saying towel*(=subject)* two-flat-thing-ly exists.

So when we say タオルが一枚しかありません,

the subject is towels,

then we have the counter 一枚 and that is marked by しか.

So we’re selecting one flat thing, one towel,

and then inverting the selection to all towels.

Not all flat things, because we’ve already marked the subject as towel.

So we’re inverting the counter, which is working adverbially,

from one towel to every towel but that one towel.

So we’re saying towels, everything but one, non-exists.

In natural English, There’s only one towel.

タオルが一枚しかありません

And that’s how what we might call

the inverse-selection structure of a しか sentence works.

しかない (Colloquial)

And I should just add at the end that

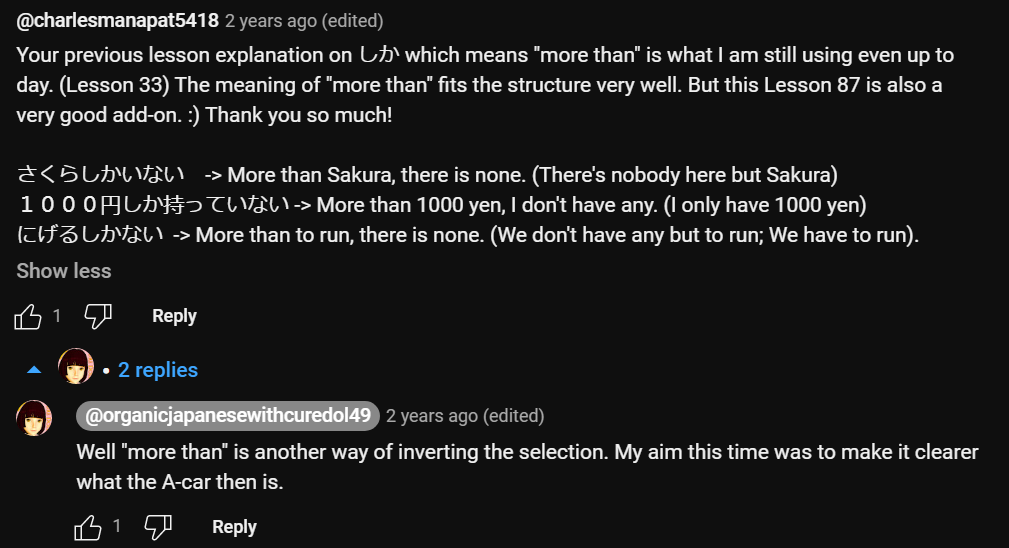

there is a use of しか that’s more colloquial.

And this is when we say しかない.

Now, in an ordinary しか sentence obviously

we just say この古い車しかない,

which means in natural English There’s only this old car.

We’re selecting the car, inverting the selection:

all cars other than this old car non-exist.

But we can also put that しかない at the end of a logical clause

or a verb standing in for a logical clause.

Now, this isn’t strictly grammatical, but colloquially it often happens.

So if you hear in an anime somebody saying 逃げるしかない!,

they’re saying (we) gotta run! in natural English.

What they’re literally saying is, we take this 逃げる,

we mark it with しか so that what we’re selecting

is not 逃げる (run) but everything else other than run.

And again, the relevancy smart selection comes in here.

What we’re really saying is

every course of action other than running (away) doesn’t exist.

Well, of course it does exist, this is very colloquial,

but as far as we’re concerned it doesn’t exist:

there’s nothing for it but to run (away).

In English we might say, It’s run or nothing,

and again, that’s ungrammatical and for the same reason

that the Japanese is ungrammatical, that run isn’t a noun.

But, when that thing’s coming after you, who cares about grammar?.

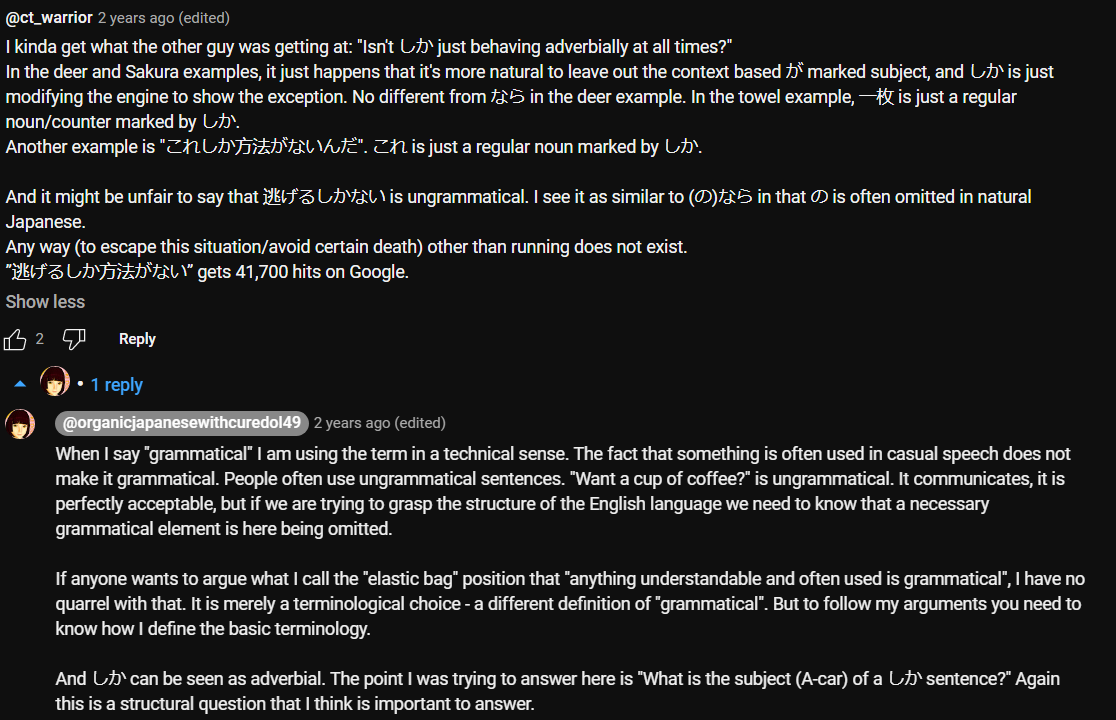

::: info

Some useful comments I guess under the video…

:::

One miscellaneous about くせに (癖に?), for the full lesson, she made this video / Lesson 93